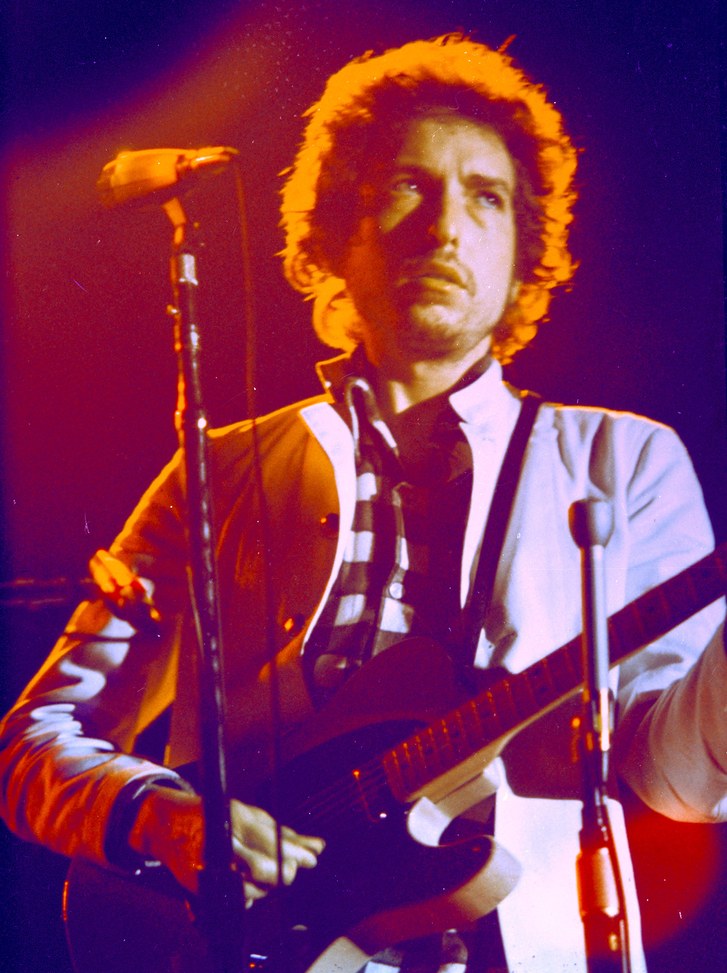

Blurring appearance and reality … Keanu Reeves and Hugo Weaving in The Matrix. Photograph: Rex Features

“In societies where modern conditions of production prevail, all life presents as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation.”

With echoes of the most rapier-like prose written by Marx and Engels (eg “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles”), so begins Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle, the treatise on the modern human condition he published in 1967. It quickly came to be seen as the set text of the Parisian événements of the following year, and has long since bled into the culture via no end of people, from the Sex Pistols to the Canadian troublemakers who call themselves Adbusters.

Its title alone is now used as shorthand for the image-saturated, comprehensively mediated way of life that defines all supposedly advanced cultures: relative to what Debord meant by it, the term usually ends up sounding banal, but the frequency with which it’s used still speaks volumes about the power of his insights. Put another way, there are not many copyright-free monographs associated with arcane leftist sects that predicted where western societies would end up at 40 years’ distance, but this one did exactly that.

The Society of the Spectacle maps out some aspects of the 21st century directly: not least, so-called celebrity culture and its portrayal of lives whose freedom and dazzle suggest almost the opposite of life as most of us actually live it. Try this: “As specialists of apparent life, stars serve as superficial objects that people can identify with in order to compensate for the fragmented productive specialisations that they actually live.” The book’s take on the driving-out of meaning from politics is also pretty much beyond question, as are its warnings about “purely spectacular rebellion” and the fact that at some unspecified point in the recent(ish) past, “dissatisfaction itself became a commodity” (so throw away that Che Guevara T-shirt, and quick).

But there are also very modern phenomena that fit its view of the world: when Debord writes about how “behind the masks of total choice, different forms of the same alienation confront each other”, I now think of social media, and the white noise of most online life. All told, the book is full of sentences that describe something simple, but profound: the way that just about everything that we consume – and, if we’re not careful, most of what we do – embodies a mixture of distraction and reinforcement that serves to reproduce the mode of society and economy that has taken the idea of the spectacle to an almost surreal extreme. Not that Debord ever used the word, but his ideas were essentially pointing to the basis of what we now know as neoliberalism.

Some brief history. Debord was the de facto leader of the Situationist International, a tiny and ever-changing intellectual cell who drew on all kinds of influences, but whose essential worldview combined two elements: an understanding of alienation traceable to the young Marx, and an emphasis on what left politics has never much liked: the kind of desire-driven irrationality celebrated by both the dadaists and surrealists. The ideas in The Society of the Spectacle drew on obvious antecedents – Hegel, Marx, Engels, the Hungarian Marxist George Lukacs – and also pointed to what was soon to come: not least, postmodernism, and the “hyperreality” diagnosed by Jean Baudrillard.

To sum up the book’s substance in a couple of sentences is a nonsense, but here goes: essentially, Debord argues that having recast the idea of “being into having”, what he calls “the present phase of total occupation of social life by the accumulated results of the economy” has led to “a generalised sliding from having into appearing, from which all actual ‘having’ must draw its immediate prestige and its ultimate function.”

Like most of The Society of the Spectacle, you have to read such words slowly, but they hit the spot: he is talking about alienation, the commodification of almost every aspect of life and the profound social sea-change whereby any notion of the authentic becomes almost impossible. Whether their writers knew anything about Debord is probably doubtful, but as unlikely it may sound, one way of opening your mind to the idea of the spectacle is maybe to re-watch two hugely successful movies about exactly the blurring of appearance and reality that he described: The Matrix and The Truman Show.

It’s also an idea to read The Revolution of Everyday Life by Debord’s one-time accomplice Raoul Vaneigem, which works as a companion piece to The Society of the Spectacle. Vaneigem writes more in a more human register than Debord, and is a more straightforward propagandist:

“Inauthenticity is a right of man … Take a 35-year-old man. Each morning he takes his car, drives to the office, pushes papers, has lunch in town, plays pool, pushes more papers, leaves work, has a couple of drinks, goes home, greets his wife, kisses his children, eats his steak in front of the TV, goes to bed, makes love, and falls asleep. Who reduces a man’s life to this pathetic sequence of cliches? A journalist? A cop? A market researcher? A socialist-realist author? Not at all. He does it himself, breaking his day down into a series of poses chosen more or less unconsciously from the range of dominant stereotypes.”

The words point up something very important: that the spectacle is much more than something at which we passively gaze, and it increasingly defines our perception of life itself, and the way we relate to others. As the book puts it: “The spectacle is not a collection of images, but a social relation among people, mediated by images.”

How we confront the spectacle is a subject for another piece: in essence, the Situationists’ contention was that its colonisation of life was not quite complete, and resistance has to begin with finding islands of the authentic, and building on them (though as what some people call late capitalism has developed, such opportunities have inevitably shrunk, a fact captured in the bleak tone of Debord’s 1989 text Comments on the Society of Spectacle, published five years before he killed himself). In truth, the spectacular dominion Debord described is too all-encompassing to suggest any obvious means of overturning it: it’s very easy to succumb to the idea that the spectacle just is, and to suggest any way out of it is absurd (which, in a very reductive sense, was Baudrillard’s basic contention).

What is incontestable, though, is how well the book, and Debord’s ideas, describe the way we live now. The images that stare from magazine racks prove his point. The almost comic contrast between modern economic circumstances and what miraculously arrives to disguise them – the Queen’s Jubilee, the Olympics – confirms almost everything the book contains. My battered copy features a much-reproduced photograph from post-war America: an entranced cinema audience, all wearing 3D glasses. But when I read it now, I always picture the archetypal modern crowd: squeezed up against each other, but all looking intently at the blinking screens they hold in their hands, while their thumbs punch out an imitation of life that surely proves Debord’s point ten thousand times over.