Posted: January 9, 2013 | Author: Kathryn | Filed under: Music | Tags: bowie, modernism, music, poetry, ts eliot,william burroughs |

Fragmented language, Nietzschean elitism, and disillusionment with art: could Bowie’s Thin White Duke era have been inspired by The Waste Land?

-Kathryn Bromwich

Submitted for MA in English: Issues in Modern Culture, University College London, 2009.

Shorter, snappier version here.

T.S. Eliot’s early work, particularly The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (1917) and The Waste Land(1922), and David Bowie’s Low (1977), are considered to be ground-breaking in their respective genres of poetry and music. Both antagonise the reader or listener with fragmented language and obscure references, and are united by a similarity in tone: disillusionment with art and distrust of language. Through a discussion of the influence of Eliot on Bowie, this essay will examine the motivation behind the aesthetic choices in both artists, and the ways in which they strive to bring about ‘newness’. The trend in 1970’s rock towards experimentation and intellectualism is well exemplified by Bowie’s interest in literature in 1977; the link between him and Eliot appears to be considerable, and can be seen as a symptomatic example for a wider movement of innovation in music. The focus will be on Low, in relation to Eliot’s early poetry and the critical writings of Eliot and Ezra Pound, in order to illustrate the ways in which Modernist ideas, themselves incorporating musical aspects, function when applied to the field of music.

The disciples of Eliot are numerous, but one who is not often discussed is David Bowie. Passing through William Burroughs, it is possible to establish an indirect influence of Eliot on Bowie. Hugo Wilcken, in his extended analysis of Low, states that Bowie’s lyrics were often composed in a ‘cut-up writing style, derived from William S. Burroughs,’[1] who in turn referred to The Waste Land as ‘the first great cut-up collage’[2] and ‘terrifically important […] I often find myself sort of quoting it or using it in my work in one way or other.’[3] However, there is also a more concrete link to Eliot. Three years before Low was released, Burroughs interviewed Bowie and remarked:

Burroughs: I read this ‘Eight Line Poem’ of yours and it is very reminiscent of T.S. Eliot.

Bowie: Never read him.

Burroughs: (Laughs) It is very reminiscent of ‘The Waste Land.’[4]

Given that Bowie considered Burroughs to be ‘the John the Baptist of postmodernism,’[5] it appears likely that this encounter would have encouraged Bowie to read Eliot.

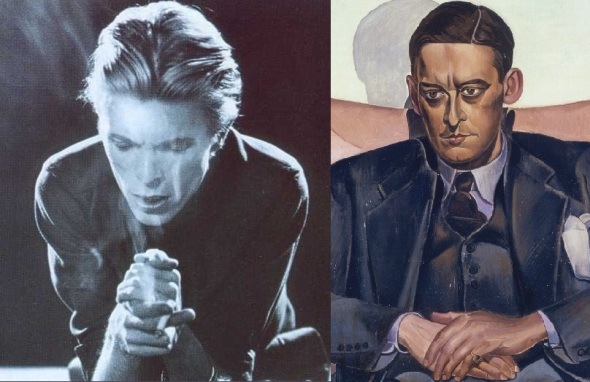

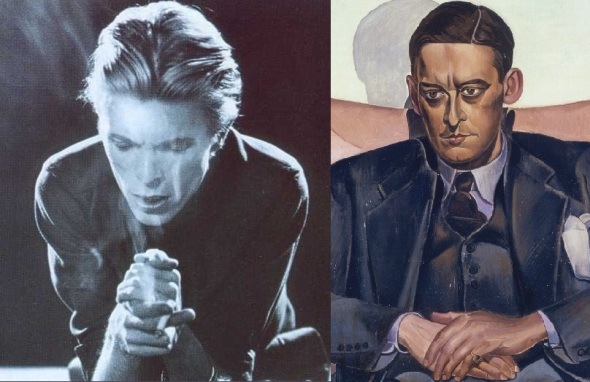

Momentarily leaving aside musical and poetic aesthetics, it is worth noting the similarities between Bowie and Eliot from a biographical point of view. Bowie constructs different ‘characters’ in relation to the music he is creating, and during the recording of Low assumed a persona that bore striking similarities to Eliot’s early characteristics: the ‘Thin White Duke.’ Bowie’s new character, much like Eliot, was interested in mysticism and the occult, and both entertained a certain amount of quasi-Nietzschean intellectual elitism, coupled with conservative views. Eliot’s biographer Peter Ackroyd relates that the reactionary poet, in his early years, ‘despised democracy’[6]; similarly, in 1976 Bowie claimed to ‘believe very strongly in Fascism […] a right-wing, totally dictatorial tyranny.’[7] Nervous and eccentric behaviour is another point in common: Eliot is known to have occasionally worn green face powder and to have demanded to be called ‘Captain,’[8] and there are rumours that Bowie preserved his urine in the fridge to avoid being cloned by aliens.[9] The Thin White Duke’s fashion sense also seems to be modelled on Eliot’s dandyish appearance: pale, thin, with slicked-back hair, austere black and white clothes, a fedora hat and black overcoat (see photos). It is impossible to say what came first – whether a longing for newness, or the interest in Eliot – but both Eliot and Bowie showed similar signs of frustration with contemporary poetry and music.

Both The Waste Land and Low were composed in volatile political times. In the chaotic aftermath of World War One, it has been argued that experience was fractured by factors such as shell-shock, loss of faith in progress, fear, grief and apathy. In poetic circles there was an increasing distrust of language: in his essay ‘The Perfect Critic,’ Eliot laments the ‘tendency of words to become indefinite emotions,’[10] and symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé criticises language’s ‘”pedestrian clarity” full of “plagiarism” and “platitudes.”‘[11] Paul Fussell argues that there was also a gap between a reality that had been wrecked by modern technologies and a language that had been ‘used for over a century to celebrate the idea of progress.’[12] At this time, poetry was mainly discursive, in traditional verse forms, and reliant on a clear understanding of its semantic meaning. Given the fragmentation of post-war consciousness, this traditional form of poetry was felt to be unsatisfactory for commenting on the new world.

In the late 1970’s, Bowie was in Berlin, perhaps the place in which the escalating tension and anxiety of the Cold War were felt most keenly. Due to the concrete separation of East and West comprised in the Berlin Wall, the city was considered ‘a microcosm of the Cold War.’[13] The atmosphere was austere: Bowie described West Berlin as ‘a city cut off from its world, art and culture, dying with no hope of retribution,’[14] and Tony Visconti said that ‘you could have been on the set of The Prisoner.’[15] The dominant form of music was largely guitar-based narrative rock, and Bowie, claiming that he was ‘intolerably bored’[16] with narration, says that his objective for Low was ‘to discover new forms of writing. To evolve, in fact, a new musical language.’[17] However, after the ‘classic’ era of Elvis and early Beatles, the music scene had already undergone several movements towards experimentation in the late ’60s. There were concept albums such as Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon (1973) and The Who’s Tommy (1969), the prog-rock movement emerged, there was an interest in virtuoso performances such as Hendrix, and in Germany the electronic movement was gaining momentum. Bowie, at a stage in music when everything seemed to have been done before, felt that ‘rock ‘n’ roll is dead… It’s a toothless old woman.’[18] His endeavour to achieve novelty, therefore, seems to operate simultaneously with a fear that nothing new can be done.

In addition to the problematical outside world, Eliot’s and Bowie’s psychological conditions were far from stable. Eliot was diagnosed with ‘some kind of nervous disorder’[19] and composed The Waste Land ‘in a state of extreme anxiety.’[20] Wilcken argues that Bowie was suffering from paranoia[21]and borderline schizophrenia.[22] Both outer and inner worlds became increasingly difficult to express through language: this posed the problem of conveying ‘non-verbal awareness by verbal means.’[23]One of Bowie’s and Eliot’s main preoccupations is a distrust of semiotics, lamenting the impossibility of precise utterance. In Prufrock, the speaker attempts to talk, although ‘it is impossible to say just what I mean,’ and what comes out is ‘not it at all, that’s not what I meant at all.’ The ‘overwhelming question’ that Prufrock cannot articulate, becomes in Bowie a need to say something that seems inexpressible: ‘What you gonna say to the real me, / Ahhhh, ahhhh, ahhhh, ahhhh, ahhh’ in ‘What in the World.’ What is said, if indeed something is, is never revealed. If art were to express the fragmented idiom of shell-shock and war, and of drug-induced, nervous consciousness, music and poetry needed a new ‘language’.

In order to avoid semantic imprecision, both Eliot and Bowie’s work becomes increasingly non-linguistic. The focus is brought towards aspects other than the words. Eliot juxtaposed obscure references and worked through association, making his words deliberately obfuscating:

Son of man,

You cannot say, or guess, for you know only

A heap of broken images (The Waste Land Part I, 20-22)

There is a move away from blank verse and iambic pentameter towards free verse, and Eliot concentrated on the poem’s visual and spatial elements, bringing attention to the form of the poem. Lines and stanzas are of different lengths, unevenly spaced and sometimes indented; different sections are divided by lengthy ellipses (the ‘…..’ in Prufrock) and visually alarming capital letters are used, for example ‘HURRY UP PLEASE ITS TIME’ (II, 141). Similarly, Bowie attempts to eschew words: his collaborator Brian Eno claims that one of the aims of Low was ‘to get rid of the language element.’[24] The music in Low is mainly instrumental, with occasional chanting, and the few lyricsare fragmented and enigmatic. The opening song ‘Speed of Life’ was Bowie’s first instrumental track, and ‘Side B’ is almost wordless. ‘Warszawa’ is in a made-up language, using voice as texture rather than as a vehicle for meaning: ‘He-li venco de-ho/ Che-li venco de-ho/ Malio.’ This recalls Eliot’s ‘Weialala leia / Wallala leialala,’ (III, 290-291) which in turn returns to Dadaist sound poetry. Bowie also foregrounds the artificial procedure of studio intervention: Low relies on synthesisers and distortion of traditional instruments with the Harmonizer, an electronic pitch-shifting device. The relevance of the songs’ linguistic meaning is minimised, while attention is drawn to the process of creating art: the form, indeed, becomes the content.

Bowie and Eliot also draw attention to style by subverting expectations, making us aware of clichéd artistic formulae. In Prufrock, Eliot leads us to expect a romantic poem, but the Laforguean mood change is abrupt:

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherised upon a table

Many of the songs on Low also defy convention: in Wilcken’s words, they ‘fade out just as the riff is starting to sink in. Just at the moment you think it might be leading somewhere, it’s gone’ (78). ‘Sound and Vision’ starts off in a loop, suggesting another instrumental song like ‘Speed of Life’: however, Bowie’s vocals appear halfway through, change pitch and intonation between lines, and refuse to develop into a structured refrain. The lines ‘drifting into my solitude/ over my head’ are sung in a crescendo, intimating a chorus or climax; on the contrary, the song fades out and ends, creating a sense of unfulfilled frustration. Form begins to merge with content, echoing Eliot’s statement that in poetry ‘we cannot say at what point “technique” begins or where it ends.’[25]

In The Waste Land, the empty spaces on the page suggest an implied score, a harmony that could perhaps unify the inchoate fragments of the poem: it seems to be yearning for a unifying key, perhaps music. The poem moves away from an emphasis on clear semantic denotation, and the form itself creates its meaning. In this respect, Eliot’s poetry can be said to approach ‘pure form’ and therefore, in Walter Pater’s words, ‘aspire towards the condition of music.’[26] Bowie also removes the non-musical elements of lyrics and narrative from his work, instead conveying his meaning through the tone and structure of his instrumental songs, thereby approaching a purer form of music. Given Eliot’s and Bowie’s distrust of language, music is an appropriate form to turn to.

The dialogue and mutual influence between music and poetry is an ongoing one, and has given rise to numerous disputes as to whether music can ever portray emotion exactly. Brad Bucknell points out that there has traditionally been a ‘romantic belief in the expressive potential of music’ (2) notably in Arthur Schopenhauer’s dictum that it is ‘a direct image of the Will itself.’[27] Pound stated that ‘poets who will not study music are defective,’[28] and that they can achieve ‘an “absolute rhythm” […] which corresponds exactly to the emotion or shade of emotion to be expressed’[29] by incorporating musical elements in poetry, thus communicating at a pre-verbal level. Eliot believed that, though technical musical knowledge was not necessary, ‘a poet may gain much from the study of music’[30] in terms of rhythm and structure. Musical technique can be used to convey meaning through melody, rhythm, tone, tempo and through what Roland Barthes would term ‘the signifying opposition of the piano and the forte.’[31] However, the signification of a polysemic medium such as music is intrinsically imprecise. The more recent critical consensus tends to be that music is important due to its ability for open signification: Mallarmé valued it precisely for ‘its imprecise, evocative effects.’[32] Eliot’s and Pound’s poetry most resembles music in its calculated ambiguity and its emphasis on impressions: their poetry could be seen, in Kevin Barry’s words, as an ‘activity of response as opposed to notions of description or specific naming.’[33] Eliot, Pound and Bowie approach the form of ‘pure music’ in their move towards polysemy, adopting music’s resistance to state anything as ‘truth’.

Instead of attempting to offer a single, clear message and being misunderstood due to the imprecision of language, the works are imbued with multiple unfixed meanings. Several denotations are condensed into single words: Winn states that the poet ‘alters the meaning of a word by multiplying its secondary associations in order to drown out the dictionary definition’ (332). There is an emphasis on polysemy and logopoeia, taking into account secondary meanings and word connotations. Eliot stated that ‘in The Waste Land, I wasn’t even bothering whether I understood what I was saying’[34]: Ackroyd praises it for providing ‘a scaffold on which others might erect their own theories’ (120). The preface to The Waste Land suggests that there is a message hidden in the poem’s fragments, like the Sybil of Cumae’s riddles. Eliot underlines the importance of ambiguity: ‘poets in our civilisation, as it exists at present, must be difficult […] the poet must become […] more allusive, more indirect, in order to force, to dislocate if necessary, language into his meaning.’[35] Similarly, Bowie’s often-abstract lyrics are held together by association and alliteration:

Don’t you wonder sometimes

‘Bout sound and vision

Blue, blue, electric blue

That’s the colour of my room

Bowie’s collaborator Brian Eno stated that ‘the interesting place is not chaos, and it’s not total coherence. It’s somewhere on the cusp of those two.’[36] Paradoxically, the mimetic method can be seen as more accurate for describing a chaotic modern consciousness than a diegetic one. In order to convey thought processes, Eliot wrote ‘What the Thunder Said’ ‘at one sitting in a kind of delirium, rather like automatic writing, aiming to replicate a free-associational structure.’[37] Bucknell argues that ‘the text’s very disruptions are meant to be the sign of continuity with our mode of perception. They are intended to be mimetic of our process of knowing the world’ (109). The works’ deliberate ambiguity, and their reluctance to offer a final truth, reflects the uncertainties of perception and thought processes in real life.

Defying the notion of a single message, Bowie and Eliot also challenge the idea of a single, fixed identity. Eliot maintains a ‘tension between performer and performed,’[38] echoing poet Arthur Rimbaud’s paradoxical ‘Je est un autre’. Both Bowie and Eliot hide their own personality by giving a voice to numerous different characters. In Prufrock, Eliot writes that ‘there will be time/ to prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet,’ suggesting a deliberate creation of identity. The Waste Land, originally entitled ‘He Do the Police In Different Voices,’ provided an outlet to the thoughts and speech of ”characters’ which seemed to exist within the personality of Eliot.’[39] These include men, women, and a synthesis of the two: Tiresias, ‘old man with wrinkled dugs’ (III, 228). A voice is given to both the aristocracy and the working classes, ‘O is there, she said. Something o’ that, I said’ (II, 150). Bowie, known for his ‘chameleonic character,’[40] has impersonated alter-egos such as Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane and the Thin White Duke. In the guise of the Thin White Duke, he splits into further additional characters on Low: ‘Be My Wife’ is sung in a theatrical cockney accent, ‘Warszawa’ suggests someone from Eastern Europe, and ‘Breaking Glass’ is performed in a terse, unemotional voice. It is difficult to gauge the artist’s true intention, or which character voices the views closest to his own.

Often, attribution of speech to any one character is problematic: Eliot’s speakers and the characters they refer to are not clearly differentiated. In passages such as ‘when we came back […] / your arms full, and your hair wet, I could not / speak’ (I, 36-9) it is up to the reader to decide who ‘we’, ‘you’ and ‘I’ are. In Bowie, lines like ‘you’re such a wonderful person, but you’ve got problems,’ and ‘deep in your room, you never leave your room’ could be spoken both by and about his paranoid persona. It is often difficult to assess whether Eliot and Bowie are to be taken seriously or in jest. In The Waste Land, Eliot’s verses ‘veer close to parody or pastiche,’[41] occasionally indicating his lifelong fondness for the music-hall.[42] In Bowie, the passage ‘please be mine/ Share my life/ Stay with me/ Be my wife,’ could be a parody of traditional pop songs, yet Bowie has stated that ‘it was genuinely anguished, I think’[43] (emphasis mine), further reinforcing the sense of ambiguity. The polyphonic juxtaposition of speakers undermines the idea of one central voice or of one ‘correct’ meaning: we are never sure who the ‘real’ Bowie or Eliot is.

In The Waste Land and Low there is a move away from a portrayal of the self or of the poet’s own thoughts: their feelings are projected onto their surroundings and other minds. Eliot states that ‘the progress of art is a continual self-sacrifice, a continual extinction of personality.’[44] This is demonstrated in his endeavour to depict the ‘Unreal City’ (I, 60) that was post-War London: Eliot ‘agonised over the fate of Europe represented archetypally in the image of London.’[45] Robert Schwartz has seen this as Eliot ‘transmut[ing] personal experience into something of greater dimension while obscuring its autobiographical origins’ (46). The songs on ‘Side B’ of Low are, on the surface, about places: Warsaw, West Berlin, the Berlin Wall, and East Berlin. The tone becomes bleaker, reaching its darkest moment in the final song ‘Subterraneans,’ in which ordinary language creates inscrutable sentences: ‘Care-line driving me/ Shirley, Shirley, Shirley own/ Share bride failing star,’ defamiliarising normal English words and generating a sense of unease. The beginning is slow, juxtaposing violins and synthesisers, and later a lone saxophone is set against a background of muted electonica; the feeling is one of isolation, appropriate for the living conditions in East Berlin. However, according to Wilcken Bowie saw the outside as ‘a reflection of the self, until you lose sight of where the self stops and the world begins’ (77). On the album cover, Bowie’s hair blends into the orange background, ‘underlining the solipsistic notion of place reflecting person.’[46] The self is effaced with the intention of making art that is universal rather than personal; however, the distinction between outside and inside is not as clear as it first appears.

The interest in place rather than the individual is especially relevant in the light of Eliot’s and Bowie’s locations. They were both on self-imposed exiles: Eliot emigrated from America to England, and Bowie moved to Germany after a few years in Los Angeles. This move towards Europe involved an increase in erudition to culturally distance themselves from America, where according to Eliot ‘the [intellectual] desert extended à perte de vue, without the least prospect of even desert vegetables.’[47] Eliot rejected the increasingly democratised American art scene of Wallace Stevens and William Carlos Williams, whose poetry was ‘in plain American which cats and dogs can read.’[48] Eliot’s poetry is laden with literary allusions, often foreign: at the end of The Waste Land, Eliot references Dante, Kyd, Gérard de Nerval, the Pergivilium Veneris and the Upanishad. Bowie left Los Angeles, moving away from the euphoric escapism of the glam, punk and disco, and embraced Europe’s avant-garde music scene. His years in Berlin were a time of intense intellectual study: he ‘amassed a library of 5000 books and threw himself into reading them […] it became something of an obsession.’[49] Infamously, the feeling of intellectual achievement gave rise to elitism and Nietzschean delusions in the young Eliot and the Berlin-era Bowie. Ackroyd relates that Eliot ‘divided human beings into ‘supermen,’ ‘termites’ and ‘fireworms’ […] there is no doubt that he felt a certain intellectual superiority’ (96). In 1978 Bowie dubbed himself and Eno the ‘School of Pretention.’[50] This sense of self-importance resulted in a propensity to showcase their erudition through extensive referencing.

In their reading, Eliot and Bowie both encountered occult rituals, oriental religion and Eastern philosophy. While writing The Waste Land, Eliot contemplated ‘withdrawal into the hermitage of a Buddhist monastery;’[51] and ”psychic’ phenomena held a certain fascination for him.’[52] The methods of the occult are related structurally to the open-ended meanings of The Waste Land: Madame Sosostris gives out knowledge in fragments out of which we hope to construct meaning, but there are things which she, too, is ‘forbidden to see’ (I, 54). The poem ends by referencing the Upanishad: ‘Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata. / Shantih shantih shantih’ (V, 433-4). The Modernist interest in mysticism filtered through to ’60s and ’70s musicians, famously the Rolling Stones and the Beatles, and features prominently in Bowie. He had an ‘interest in Buddhism,’[53] a fascination with Aleister Crowley,[54] and his work abounds in allusions ‘to Gnosticism, black magic and the kabbala.’[55] The cryptic lyric ‘don’t look at the carpet, I drew something awful on it’ in ‘Breaking Glass’ is a reference to the Tree of Life. Although the interest in Eastern culture and occult rituals is not exclusive to Eliot and Bowie, it underlines their sense that conveying certain thoughts and feelings in standard English was impossible. In their work, they therefore incorporate different perspectives on the world, drawing inspiration from external sources.

One of the most striking similarities between Eliot and Bowie is the abundance and openness of their references to old, foreign, and ‘low’ sources. Another, possibly more conventional way of bringing about change, would be to embrace the new entirely and make a clean break with the past: Frank Kermode states that ‘the urge to be radically new is itself part of an ongoing history.’[56] The manifesto of Futurism in the 1910s was to reject classical art and ‘demolish museums and libraries’[57]; the American Modernist poetry of Stevens and Williams in the 1930s concentrated on ‘the local.’ The ‘robot rhythms’ of Krautrock in the mid-1970s ‘were in the process of eliminating the human altogether from the beat.’[58] Conversely, and perhaps counterintuitively, Eliot and Bowie both allude to traditional forms of their particular art in their attempt to modernise themselves. Eliot argued for a need of the timeless in addition to the temporal, stating that the artist cannot be valued alone but ‘must inevitably be judged by the standards of the past.’[59] Perhaps motivated by a disillusionment with the modern, Eliot and Bowie turn towards their predecessors.

Eliot frequently references classical literature in his work. The Waste Land starts with a reference to spring weather, recalling Chaucer’s ‘Aprille with his shoures sote.’[60] In ‘so many, / I had not thought death had undone so many’ (I, 62-3), Eliot translates Dante almost word-for-word: ‘io non averei mai creduto / che morte tanta n’avesse disfatta.’[61] Direct quotes are included as well, from Shakespeare (‘those are pearls that were his eyes’ I, 48) to Baudelaire (‘hypocrite lecteur! – mon semblable, – mon frère!’ I, 76). Myth was also important: in his essay ‘Ulysses, Order and Myth’ Eliot states that Joyce’s use of the Odyssey ‘has the importance of a scientific discovery […] instead of narrative method, we may now use the mythical method.’[62] Along these lines, The Waste Land is often said to be based on the quest for the Holy Grail.[63] Bowie, in turn, alludes to old, traditional and foreign music in Low.These include chanting in ‘Warszawa,’ a harmonica in ‘A New Career in a New Town’, a ragtime riff in ‘Be My Wife’, and a saxophone in ‘Subterraneans’. In ‘The Weeping Wall’, xylophones that Philip Glass compared to Japanese bells[64] are used to create ‘the flavour of Javanese gamelan (traditional Indonesian orchestras).’[65]

The allusions to older forms of poetry and music, however, are set against innovative techniques. Eliot’s untraditional versification is at odds with the classical poets he references, and Bowie’s synthesiser sounds especially futuristic when contrasted to ragtime piano jingles. In returning to the past rather than rejecting it completely, Bowie and Eliot seem to question the concept of innovation itself. The method of referencing old and foreign sources differs from other methods of modernisation in its admission that it does not function in a cultural vacuum, and that is not – and cannot be – original. Experimental music combining old and new genres had been done before Bowie, notably in Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967); however, Bowie is set apart from their intentional experimentation by his attitude of disillusionment with art and originality. His creation of personas and unremitting self-reinvention distances him from his music; his embracing of commodified, commercial pop in the 80’s with hits such as ‘Under Pressure’ and ‘Let’s Dance,’ could be seen as indicating a sense of ironic detachment.

The assertion that originality is a myth is a constant source of frustration in both works, and, in itself, becomes a central subject. Eliot believes that he has nothing new or momentous to say: he talks of ‘Nothing again nothing. / Do / You know nothing? Do you see nothing? […] Is there nothing in your head?’ (II, 120-126) and Bowie laments that there is ‘nothing to do, nothing to say’ in ‘Sound and Vision.’ Ackroyd posits that Eliot ‘was immensely susceptible to [the ideas] of others – the act of creation was for him the act of synthesis’ (106). Brian Eno suggests a similar idea: ‘some people say Bowie is all surface style and second-hand ideas, but that sounds like a definition of pop to me.’[66] In Barthes’ terms, rather than projecting themselves as ‘authors’, entirely original lone geniuses, they are ‘scriptors’, in whose work ‘a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash.’[67] They place themselves in the context of past artwork, with no pretence of ‘pure originality.’

The apparently unrelated fragments, however, cohere: the fragments are arranged according to meaningful associative links, even if these are left unclear. Eliot said of Saint-John Perse’s poem Anabasis that ‘any obscurity of the poem, on first readings, is due to the suppression of links in the chain, of explanatory and connecting matter, and not to incoherence’[68]: as Schwartz points out, this description is also appropriate for The Waste Land. No matter how innovative the method, Eliot believes that ‘to conform merely [to any one method] would not be new, and would therefore not be a work of art.’[69] Eliot and Bowie therefore bring together ‘particles which can unite to form a new compound’[70]: a synthesis of old and new. Both works, bringing to light the impossibility of originality, are characterised not by an intrinsic ‘newness’, but by a Modernist yearning for the new.

In conclusion, it seems likely that Bowie had first-hand contact with the works of T. S. Eliot. The music inspired by Low could therefore be seen as obliquely descending from literary Modernism. When applied to music, Eliot’s aesthetics result in a disjointed, evocative, largely instrumental effect: a new musical language. Both works are marked by disillusionment with language and a move towards ‘pure form,’ aiming to minimise their dependence on semantic meaning or narrative. They work through associative and mimetic techniques: the content is made ambiguous, giving priority to the form. Different views are expressed through a polyphonic variety of voices, signalling a move away from any single meaning and encouraging a subjective interpretation of their work. The use of old and foreign sources reminds us that art must be considered in its context, drawing our attention to the inspirations that allow it to come into being: the myth of ‘originality’ in art is dispelled. The eclectic fragments in both The Waste Land and Low, then, are held together by a desire for newness, which is nevertheless tempered by a belief that originality is impossible.

[1] Hugo Wilcken. Low. (NY and London: Continuum, 2005), 82.

[2] William Burroughs. The Third Mind. (London: John Calder, 1979), 3

[3] John May, ‘Meeting with Burroughs at the Chelsea’ (2005) <http://hqinfo.blogspot.com/2005/06/meeting-with-burroughs-at-chelsea.html> [accessed 03-01-2009]

[4] Craig Copetas, ‘Beat Godfather meets Glitter Mainman,’ from Rolling Stone (February 1974) <http://www.teenagewildlife.com/Appearances/Press/1974/0228/rsinterview> [accessed 03-01-2009]

[5] David Bowie, ‘David Bowie Remembers Glam,’ The Guardian (02-04-2001) <http://www.guardian.co.uk/culture/2001/apr/02/artsfeatures.davidbowie> [accessed 03-01-2009]

[6] Peter Ackroyd. T. S. Eliot. (London: Abacus, 1984), 109

[7]Sarfraz Manzoor, ‘1978,’ The Guardian 20-04-2008, quoting Bowie in Playboy (September 1976) <http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2008/apr/20/popandrock.race> [accessed 03-01-2009]

[8] Ackroyd, 136

[9] Wilcken, 11

[10] TS Eliot. The Sacred Wood. (London: Faber, 1997), 8

[11] In Brad Bucknell. Literary Modernism and Musical Aesthetics. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 31

[12] Paul Fussell. The Great War and Modern Memory. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 169

[13] Wilcken, 58

[14] In Wilcken, 119

[15] Ibid. 112

[16] In Thomas Jerome Seabrook. Bowie in Berlin. (London: Jawbone Press, 2008), 112

[17] In Wilcken, 14

[18] In Seabrook, 35

[19] Ackroyd, 113

[20] Robert L. Schwartz. Broken Images. (Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 1988), 34

[21] Wilcken, 52

[22] Wilcken, 82

[23] Aaronson in Bucknell, 2

[24] In Seabrook, 114

[25] Eliot 1997, xi

[26] Walter Pater. The Renaissance. (Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics, 1998), 86

[27] In Bucknell, 22

[28] Ezra Pound. The Literary essays. (London: Faber and Faber, 1954), 437

[29] Ibid. 9

[30] TS Eliot. On Poetry and Poets. (London: Faber, 1957), 38

[31] Roland Barthes. Image Music Text. (London: Fontana Press, 1977), 151

[32] In James Anderson Winn. Unsuspected Eloquence. (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 1981), 326

[33] Kevin Barry. Language, Music and the Sign. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 2

[34] In Schwartz, 32

[35] Eliot 1921

[36] In Wilcken, 68

[37] Schwartz, 32

[38] Keith Alldritt. Eliot’s ‘Four Quartets.’ (London: Woburn Press, 1978), 38

[39] Ackroyd, 118

[40] Seabrook, 22

[41] Ackroyd, 117

[42] Ibid. 105

[43] In Wilcken, 97

[44] Eliot 1997, 44

[45] Schwartz, 24

[46] Wilcken, 127

[47] Eliot in James Miller. TS Eliot. (Pennsylvania: Penn State Press, 2005), 139

[48] Marianne Moore, ‘England’

[49] Wilcken, 38-39

[50] Bowie 2001

[51] Schwartz, 241

[52] Ackroyd, 113

[53] Wilcken, 80

[54] Seabrook, 36

[55] Wilcken, 7

[56] In Bucknell, 14

[57] Stanley Payne. The History of Fascism. (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996), 64

[58] Wilcken, 33

[59] Eliot 1997, 42

[60] The Canterbury Tales <http://www.gutenberg.org/files/22120/22120-8.txt> [accessed 03-01-2009]

[61] Inferno III, 56-57

[62] Eliot in The Dial, LXXV (November 1923), 482

[63] Schwartz, 14

[64] In Wilcken, 19

[65] Wilcken, 124

[66] In Wilcken, 101

[67] Roland Barthes. ‘The Death of the Author’ in the Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. (NY and London: Norton, 2001), 1468

[68] In Schwartz, 37

[69] Eliot 1997, 42

[70] Eliot 1997, 45

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. T. S. Eliot. London: Abacus, 1984.

Alldritt, Keith. Eliot’s ‘Four Quartets’: Poetry as Chamber Music. London: Woburn Press, 1978.

Barry, Kevin. Language, Music and the Sign : a study in aesthetics, poetics and poetic practice from Collins to Coleridge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Barthes, Roland. Image Music Text. London: Fontana Press, 1977.

― ‘The Death of the Author,’ in The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 7th edition. Edited by Vincent B. Leitch. New York and London: Norton, 2001.

Bowie, David. Low. London: EMI, 1977.

― ‘David Bowie Remembers Glam,’ in The Guardian, Monday 2 April 2001. Accessed at http://www.guardian.co.uk/culture/2001/apr/02/artsfeatures.davidbowie on 03-01-2009.

Bucknell, Brad. Literary Modernism and Musical Aesthetics : Pater, Pound, Joyce, and Stein. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Burroughs, William S. and Brion Gysin. The Third Mind. London: John Calder (Publishers) Ltd, 1979.

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Canterbury Tales. Accessed at

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/22120/22120-8.txt on 03-01-2009.

Copetas, Craig. ‘Beat Godfather meets Glitter Mainman: Bowie meets Burroughs,’ originally printed in Rolling Stone, February 28, 1974. Accessed at

http://www.teenagewildlife.com/Appearances/Press/1974/0228/rsinterview on 03-01-2009.

Eliot, Thomas Stearns. ‘The Metaphysical Poets,’ in the Times Literary Supplement, October 20, 1921.

― On Poetry and Poets. London: Faber, 1957.

― ‘Ulysses, Order and Myth,’ The Dial, LXXV (November 1923), 481-3

― Collected Poems, 1909-1962. London: Faber and Faber Ltd, 1974.

― The Sacred Wood: Essays on Poetry and Criticism. London: Faber, 1997.

Fussell, Paul. The Great War and Modern Memory. New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Kermode, Frank. ‘Bearing Eliot’s Reality,’ in The Guardian, Thursday 27 September 1984. Accessed at http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/1984/sep/27/biography.peterackroyd on 03-01-2009.

May, John. ‘Meeting with Burroughs at the Chelsea’, accessed at

http://hqinfo.blogspot.com/2005/06/meeting-with-burroughs-at-chelsea.html on 03-01-2009.

Manzoor, Sarfraz. ‘1978, the Year Rock Found the Power to Unite,’ in The Guardian, Sunday 20 April 2008, quoting Bowie from Playboy, September 1976. Accessed at http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2008/apr/20/popandrock.race on 03-01-2009.

Miller, James Edwin. T. S. Eliot. Pennsylvania: Penn State Press, 2005.

Pater, Walter. The Renaissance. Adam Phillips, ed. Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics, 1998.

Payne, Stanley G. The History of Fascism. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996.

Pound, Ezra. The Literary essays of Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot ed. London: Faber and Faber, 1954.

Seabrook, Thomas Jerome. Bowie in Berlin: A New Career In a New Town. London: Jawbone Press, 2008.

Schwartz, Robert L. Broken Images: A Study of the Waste Land. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press; London: Associated University Presses, 1988.

Wickeln, Hugo. Low. New York and London: The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc, 2005.

Winn, James Anderson. Unsuspected Eloquence: a history of the relations between poetry and music. New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 1981.

‘Thought-tormented Music’: David Bowie’s Low and T.S. Eliot.

52.636878

-1.139759