People are almost always surprised when I tell them Stan Lee is 93. He doesn’t scan as a young man, exactly, but frozen in time a couple of decades younger than he is, embodying still the larger-than-life image he crafted for himself in the 1970s — silver hair, tinted shades, caterpillar mustache, jubilant grin, bouncing gait, antiquated Noo Yawk brogue. We envision him spreading his arms wide while describing the magic of superhero fiction, or giving a thumbs up while yelling his trademark non sequitur, Excelsior! He’s pop culture’s perpetually energetic 70-something grandpa, popping in for goofy cameos in movies about the Marvel Comics characters he co-created (well, he’s often just said “created,” but we’ll get to that in a minute) in the 1960s. But even then, he was old enough to be his fans’ father — not a teenage boy-genius reimagining the comics world to suit the tastes of his peers but already a middle-aged man, and one who still looked down a bit on the form he was reinventing.

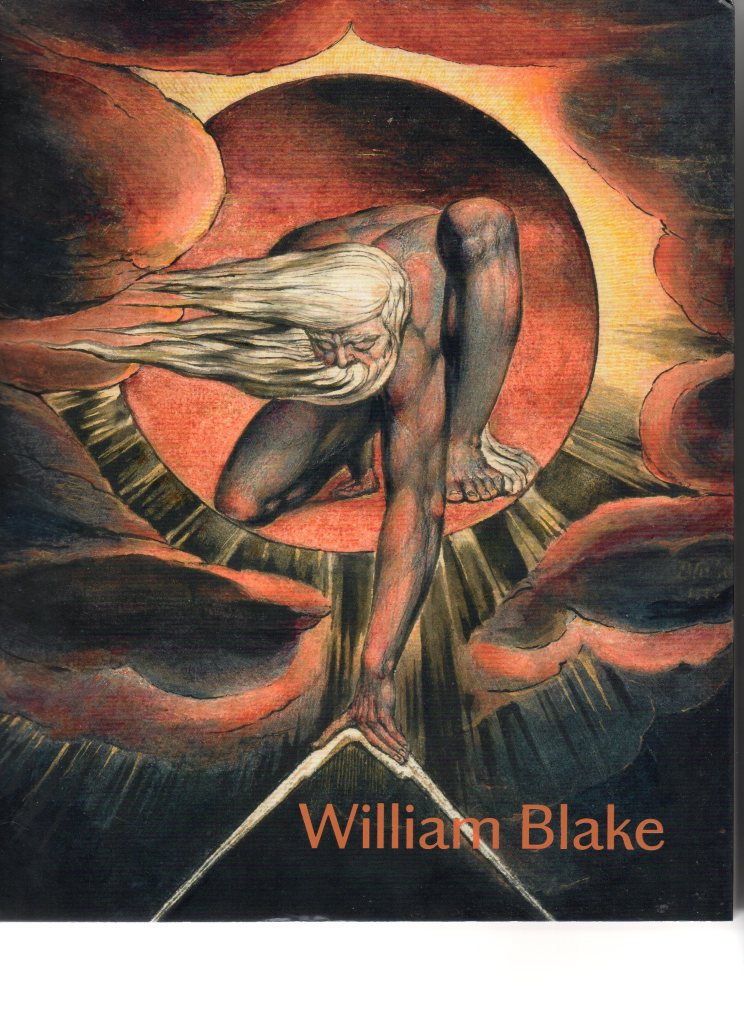

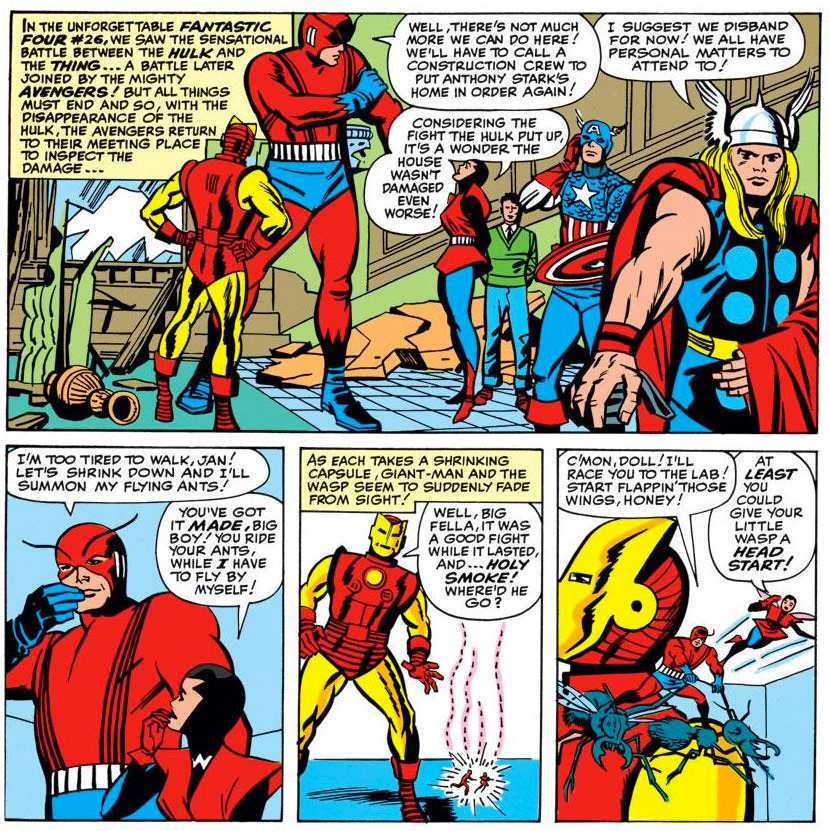

A comic-book Methuselah, Lee is also, to a great degree, the single most significant author of the pop-culture universe in which we all now live. This is a guy who, in a manic burst of imagination a half-century ago, helped bring into being The Amazing Spider-Man, The Avengers, The X-Men, The Incredible Hulk, and the dozens of other Marvel titles he so famously and consequentially penned at Marvel Comics in his axial epoch of 1961 to 1972. That world-shaking run revolutionized entertainment and the then-dying superhero-comics industry by introducing flawed, multidimensional, and relatably human heroes — many of whom have enjoyed cultural staying power beyond anything in contemporary fiction, to rival the most enduring icons of the movies (an industry they’ve since proceeded to almost entirely remake in their own image). And in revitalizing the comics business, Lee also reinvented its language: His rhythmic, vernacular approach to dialogue transformed superhero storytelling from a litany of bland declarations to a sensational symphony of jittery word-jazz — a language that spoke directly and fluidly to comics readers, enfolding them in a common ecstatic idiom that became the bedrock of what we think of now as “fan culture.” Perhaps most important for today’s Hollywood, he crafted the concept of an intricate, interlinked “shared universe,” in which characters from individually important franchises interact with and affect one another to form an immersive fictional tapestry — a blueprint from which Marvel built its cinematic empire, driving nearly every other studio to feverishly do the same. And which enabled comics to ascend from something like cultural bankruptcy to the coarse-sacred status they enjoy now, as American kitsch myth.

All of which should mean there’s never been a better time to be Stan Lee. But watching him over the last year — seeing the way he has to hustle for paid autographs at a convention, watching him announce lackluster new projects, hearing friends and collaborators grudgingly admit his personal failings — it’s hard to avoid the impression that, in what should be his golden period, Lee is actually playing the role of a tragic figure, even a pathetic one. On the one hand, the characters associated with Lee have never been more famous. But as they’ve risen to global prominence, a growing scholarly consensus has concluded that Lee didn’t do everything he said he did. Lee’s biggest creditis the perception that he was the creator of the insanely lucrative Marvel characters that populate your local cineplex every few months, but Lee’s role in their creation is, in reality, profoundly ambiguous. Lee and Marvel demonstrably — and near-unforgivably — diminished the vital contributions of the collaborators who worked with him during Marvel’s creative apogee. That is part of what made Lee a hero in the first place, but he’s lived long enough to see that self-mythologizing turn against him. Over the last few decades, the man who saved comics has become — to some comics lovers, at least — a villain.

And, to certain comics fans, something of a joke. Lee may have personally made possible an expansive comics culture populated by idiosyncratic voices telling morally complex stories about relatable characters, layered over with much more darkness than had ever come before (achievements for which he still enjoys occasional bouts of adoration from the mainstream press and casual fans). But hard-core comics geeks greet news of his new projects with a certain degree of eye-rolling. Lee has always had a penchant for overstatement, but his pronouncements have grown increasingly hollow in the past 15 years. When he says he’s doing story concepts for a new superhero movie called Arch Alien and says it “is gonna be the biggest hit of the next year,” or when he says a comic-book collaboration with Japanese pop artist Yoshiki “is gonna be like nothing you’ve ever seen before,” it’s hard not to cringe a little bit. Where is the buzz about these projects? Is anyone really paying attention? A creative radical who made his most significant contributions while still carrying a healthy bit of disdain for a corny medium, he finds himself now, on the other end of the revolution he engineered, casually disrespected by the comics vanguard for being something like, well, corny.

Still, the greatest salesman the American comics industry ever had, he continues hawking. Lee and the company he helms, POW! Entertainment (he left active duty at Marvel in the late 1990s, though he still collects a reported million-dollar annual paycheck from the superhero giant), announce a dizzying number of new projects every year. The last six months alone have seen Lee doing promotional pushes for his British superhero TV series Lucky Man, Arch Alien, the Yoshiki project, a mobile game called Stan Lee’s Hero Command (which actually came out almost a year ago), a big-screen sci-fi take on Shakespeare called Romeo and Juliet: The War, a children’s book targeted at the Chinese market called Dragons vs. Pandas, a co-written young-adult novel series called The Zodiac Legacy, and a co-written memoir (with comics scribe Peter David)* called Amazing Fantastic Incredible. ButGoogle searches for “stan lee cameo” (he still does plenty) dwarf the searches for “stan lee arch alien” or “stan lee yoshiki,” and you’ll find hardly any mentions of those projects in geek-news sites.

To be fair, the memoir and Zodiac have been released, and have produced decent sales so far. But in Lee’s current era of output, they’re the exception. As any longtime Lee-watcher can tell you, it’s anyone’s guess as to how many of his future projects will actually pan out. Ever since Lee took his talents away from Marvel, he’s left behind a trail of unfinished and half-finished work — which has made readers wonder just how much of those talents lie in narrative craft, and how much in showmanship. In 2005, Lee enthusiastically announced he’d partnered with Ringo Starr to make a cartoon where the drummer became a superhero. It never materialized. He was going to make a movie with Disney called Nick Ratchet, and it got as far as hiring writers in 2009, then vanished. A comics series called Stan Lee’s Mighty 7 released three issues in 2012 before abruptly stopping on a cliff-hanger (“The wonderment begins next time, pilgrims!” Lee’s narration read. “Miss it at your own risk! Excelsior!”) and never resuming. The list of mysteriously fizzled efforts goes on and on. And within geekdom, people tend not to talk about the stuff that does come out. Longtime friends and admirers within the comics industry will tell you, with a tone of embarrassment, that they don’t read or watch the stuff Lee produces these days. “The style of comics today is so different from the optimistic style that Stan has,” says veteran comics writer and Lee collaborator Marv Wolfman, trying to explain the decline in relevance. “Stan is very, very optimistic, and we’re sadly living in a very pessimistic world.”

The costs of that change are not merely to Lee’s reputation. The most troubling aspect of Lee’s current situation is one entirely absent from the brief, glowing, and nostalgia-tinged pieces of press coverage he gets these days: His company is dying. Its most recent filing to the Securities and Exchange Commission lamented two years of net losses, could only predict the company would survive through January 2016, and declared, “These conditions raise substantial doubt about the Company’s ability to continue as a going concern.” POW!’s stock currently trades at one cent a share.

It’s a mild October day in Southern California, but the regurgitated air inside the Los Angeles Convention Center is freezing. Lee — wearing a white shirt, beige vest, tinted shades, and his trademark grin — seems unfazed by the chill. He nimbly hops into a chair in a makeshift press area set up just a few feet away from the main stage of his annual pop-culture convention, Stan Lee’s Comikaze. At his side is one of his business partners, a media entrepreneur named Terry Dougas. They’re here to announce Dragons vs. Pandas. Dougas, wisely, plays the straight man while Stan does one of the things he does best: charm journalists.

“Stan has always been focused, of course, on helping with literacy, helping children and families,” Dougas says.

“Sure!” Lee shouts in a gravelly voice. “The more kids can read, the more they’ll buy my books!”

Dougas starts describing Dragons vs. Pandas’ complex international rollout plan, featuring a digital release, a printed book, animation, a translation into Mandarin, and more. Lee, perhaps sensing how confusing this all sounds, butts in again.

“We’re gonna do more to create peace in the world between nations than anybody else!” the nonagenarian crows, pointing at a blowup of the book’s cover. “You may not suspect this, but this little panda is a killer! And this dragon is so scared. But you gotta read the story to get it all!”

The biggest laughs come a few minutes later, during the question-and-answer period. I ask him what his and Dougas’s collaboration process is like. “We hate each other!” Lee says. “He does all the talking, the girls love him because he’s good-looking, and he just keeps me around — why do you keep me around? I haven’t figured that out yet. No, he’s great to work with. He does all the work, I take the credit. You couldn’t have a better arrangement.”

That last bit is more than a little remarkable to hear. On the one hand, he’s just doing the typical Stan routine, one he’s been doing for the better part of seven decades: putting an audience at ease via disorienting shifts between self-promotion and self-debasement. But saying he just slaps his name on other people’s work — well, that’s a topic he usually keeps off the table, even for jokes. After all, it’s unwise to draw attention to the things for which you’re most hated, and since at least the late 1960s, Lee has been accused of stealing credit from two of comics’ most legendary creators, two men who had tremendous creative synergy with Lee before they concluded that he was an unforgivable bastard. Those two men were writer-artists Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko.

When you’re a comics nerd, there comes a time in your life when someone more knowledgeable than you — an older kid at school or summer camp, the checkout guy at your local comics shop, a blogger with a vendetta — lets you in on a secret. You know Stan Lee, right? You love him, right? Well, let me fill you in on some real shit. You learn about how he screwed Kirby and Ditko, about how those two were the real creative forces behind Marvel. You get told Lee is nothing more than a flashy, empty suit. If you want proof, you dig in to chronicles of his life like Jordan Raphael and Tom Spurgeon’s Stan Lee and the Rise and Fall of the American Comic Book, or Sean Howe’s masterful Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, and you see ample evidence for the case against Lee. You force yourself to question your assumptions. You have to decide what your personal take on this iconic figure is, and how you can weigh his accomplishments against his failings. Your conception of him is never the same again.

“The story of Stan, Jack, and Steve is the stuff legends are made of,” one of Stan’s oldest friends and collaborators, comics writer-editor Roy Thomas, tells me over the phone. “It’s on them, more than any other three people, that the whole Marvel thing is built.” Thomas had an experience any comics fan or historian would kill for: He walked the offices of Marvel in the mid-’60s, when Lee and Ditko were working together on Spider-Man and Doctor Strange stories and Lee and Kirby were working together on nearly everything else, including The Avengers, The X-Men, and The Fantastic Four. Here’s the problem: It’s extremely unclear what “working together” meant.

According to Lee, it meant he came up with the concepts for all the characters, mapped out plots, gave the plots to his artists so they could draw them, and then would take the finished artwork and write his signature snappy verbiage for the characters’ dialogue bubbles. The artists, in Lee’s retelling, were fantastic and visionary, but secondary to his own vision. According to Kirby and Ditko, that’s hogwash. Ditko has retreated into a hermetic existence in midtown Manhattan, where he types up self-promoting mail-order pamphlets claiming Lee had only the most threadbare initial ideas for Spider-Man, and that Ditko is the one who fleshed the iconic character out into what he is today, then came up with most of the plot beats in any given story. Kirby, from the time he left Marvel in 1970 until his death in 1994, swore up and down that Lee was a fraud on an even larger scale: Kirby said he himself was the one who had all the ideas for the Hulk, Iron Man, Thor, and the rest, and that Lee was outright lying about having anything to do with them. What’s more, he said Lee was little more than a copy boy, filling in dialogue bubbles after Kirby had done the lion’s share of the conceptual and writing work for any given issue.

“Stan Lee and I never collaborated on anything,” Kirby told an interviewer in 1989. “It wasn’t possible for a man like Stan Lee to come up with new things — or old things, for that matter. Stan Lee wasn’t a guy that read or that told stories.”

“Stan’s gotten far too much credit,” says veteran comics writer Gerry Conway, who’s known Lee since 1970. “People have said Stan was out for No. 1, and to a very large degree, that’s true. He’s a good guy. He’s just not a great guy.”

“Unfortunately, from day one, Jack was doing part of Stan’s job, and Stan was not doing part of Jack’s job,” says comics historian Mark Evanier, who worked as Kirby’s assistant and has worked on and off with Lee since the 1970s. “When you talk to Stan Lee, when he turns the Stan Lee act off, he’s a very decent human being who is chronically obsessed with himself. He’s very insecure. Those of us who have trouble being angry for some of the things that happened, it’s because we saw the real human being there at times.”

“It’s one of those things where you sit down and you say, ‘You gotta be forgiving of your parents,’” says artist Colleen Doran, who drew Lee’s new memoir. “I don’t know of anyone who knows Stan and doesn’t love him, even if they hate things he’s done.”

To understand the nature of Lee’s bitter blood feuds, you have to take a step back and understand who Lee was before the Marvel phenomenon: a dispirited, middle-aged company stooge working in a dying industry, with no reason to believe anything could change. To understand Stan Lee, you must understand that his is one of the more remarkable second acts in American culture.

He was born Stanley Martin Lieber in Manhattan’s Upper West Side on December 28, 1922, the first child of middle-class Jewish parents. Stanley’s father, Jack, had been a dressmaker but suffered from chronic unemployment during the Depression. “Seeing the demoralizing effect that his unemployment had on his spirit, making him feel that he just wasn’t needed, gave me a feeling I’ve never been able to shake,” Lee wrote in his first memoir, Excelsior!, published in 2002. “It’s a feeling that the most important thing for a man is to have work to do, to be busy, to be needed.”

Poverty drove the family to cheaper rents in the Bronx, where the bookish Stanley attended DeWitt Clinton High School and adopted the nickname Stan Lee. He took to writing around then and snagged a few creative gigs: He wrote advance obituaries for a news service, did publicity material for a hospital, and briefly performed with the New Deal’s WPA Federal Theatre Project. His family couldn’t afford college, but as luck would have it, his cousin was married to a publisher named Martin Goodman, who had leaped into the nascent-but-booming world of comic books, a medium only invented in 1933. Lee got a gig as an editorial gofer at Goodman’s Timely Publications in 1940 and soon started writing scripts for its burgeoning lineup of titles. He usually signed them as “Stan Lee” because — so goes his oft-told anecdote — he wanted to save his real name for when he would someday write the great American novel. He’s earned a paycheck from the company, in its constantly shifting forms and names, ever since.

Upon entering the building, Lee met the most significant man in his life, someone whose partnership and eventual spite will haunt him forever: Jack Kirby, the pen name of a rough-and-tumble Jewish boy from the Lower East Side, Jacob Kurtzberg. He was a writer-artist five years Lee’s senior and already a leading light in the budding comics industry, lauded for co-creating the smash-hit superhero Captain America alongside Timely editor-in-chief Joe Simon just a few weeks prior. From the very beginning, Lee and Kirby were a study in stark contrasts. The younger man was cheerful and animated, prone to leaping around the offices while playing an ocarina; the older pro was quiet and perpetually hunched over his drawing board. Lee was healthy and handsome; Kirby was husky and shrouded in cigar smoke. And while Lee was immediately eager to please the powers that be, Kirby and Simon ran afoul of Goodman and angrily left the company in 1941. Lee, not even 19 years old, was abruptly named editor-in-chief at one of the hottest publishers in comics.

He would hold that position for two decades — a full professional career, really — before Timely transformed into Marvel (two decades characterized by diminishing returns for the business as a whole). Lee had a brief Army stint from 1942 to 1945, serving Stateside as a copywriter (both of his memoirs proudly recall the crafting of a poster reading, “VD? NOT ME!”), and though he returned to his job at Timely afterward, he was never truly satisfied there. With good reason. Goodman was a shameless trend-chaser: When superhero series like National Comics’ Superman and Batman fell out of fashion and Gleason Publications saw success with a cops-and-robbers series called Crime Does Not Pay, Goodman’s company cranked out laughably obvious knockoff versions named Crime Must Lose!, Crime Can’t Win, and Lawbreakers Always Lose. Same went for Westerns and horror when the market shifted toward those genres. Lee dutifully supervised and wrote scripts for these also-rans, drifting through corporate stability and silently seething about the material. “We’re not talking War and Peace here,” he wrote in his first memoir. “In fact, I was probably the ultimate, quintessential hack.”

Then, in the mid-1950s, the industry collapsed under the weight of a moral panic about the medium’s supposed promotion of juvenile delinquency (which prompted infamous,vicious congressional hearings). Goodman was a poor businessman and a worse boss, hemorrhaging cash and forcing the genial Lee to tell staffers they were fired. To make matters worse, death stalked Lee: He and his wife Joan’s second child died three days after birth, then his closest friend at the company, artist Joe Maneely, died after falling in front of a commuter train. As the staff dwindled, Lee was forced to stand alone as the sole writer and editor of virtually everything his boss published. “I was like a human pilot light,” he wrote in 2002, “left burning in the hope that we would reactivate our production at a future date.” Everything was in free-fall; everything was up for grabs. Lee, at age 38, had little to lose.

There are two accounts of what happened next, and they’re impossible to reconcile. According to Jack Kirby — who died in 1994 — the revolution began with uncontrollable weeping. He had returned to Martin Goodman’s company on a freelance basis in 1958, and he recalled a fateful day when the place hit rock bottom. “I came in and they were moving out the furniture, they were taking desks out,” he said in an infamous 1989 interview with The Comics Journal. “Stan Lee is sitting on a chair crying. He didn’t know what to do, he’s sitting in a chair crying — he was just still out of his adolescence. I told him to stop crying. I says, ‘Go in to Martin and tell him to stop moving the furniture out, and I’ll see that the books make money.’” In his telling, he then single-handedly conceived the characters and plot of The Fantastic Four, the quirky, iconoclastic, epoch-defining superhero series that kicked off the resurrection of the company and the industry.

Lee, as you would imagine, absolutely refutes that story and has his own oft-told version of the path to The Fantastic Four. Here’s how he put it in his 1974 book Origins of Marvel Comics: “Martin mentioned that he had noticed one of the titles published by National Comics seemed to be selling better than most. It was a book called The Justice League of America and was composed of a team of superheroes,” Lee wrote. “Well, we didn’t need a house to fall on us. ‘If The Justice League is selling,’ spake he, ‘why don’t we put out a comic book that features a team of superheroes?’” Lee didn’t want to keep churning out trend-following swill, so he said he dreamed up a superteam “such as comicdom had never known,” with characters who were “fallible and feisty, and — most important of all — inside their colorful, costumed booties they’d still have feet of clay.” He then, so the story goes, conceived the idea for The Fantastic Four by himself, typed out a pitch, and selected Kirby to draw it. Kirby, Lee said, had nothing to do with the initial idea.

This is a pattern you run into for nearly every one of the characters that followed: There’s Lee’s charming, witty account of events; there’s Kirby’s dour, workmanlike one; and never the twain shall meet. The men kept few written records from the time, and the debate over how much credit Lee deserves is the single most controversial matter in the history of comics. These matters aren’t just fanboy quibbles either: In 2009, when Marvel began to rake in cash from its film studio, the Kirby family legally declared Jack was co-creator of all those extremely lucrative characters — and that, because work-for-hire standards were so vague in the early ’60s, they were entitled to a share of the copyright on all those properties. The case went on for five years and very nearly made it to the Supreme Court before Marvel settled under terms that are believed to be quite generous. (To be fair, Lee doesn’t hold the copyrights either — he’s just remained employed by the company that does.)

But when The Fantastic Four No. 1 hit stands on August 8, 1961, all anyone outside Goodman’s offices knew was that the 25-page tale was unlike any other comic book in the medium’s 23-year history. Superhero stories were supposed to be about genial people who happily stumble upon superhuman abilities, then go on their merry way toward justice. That mold was forever broken in the four-page sequence where powers are forced onto the titular quartet — forced upon them quite painfully. Scientist Reed Richards takes his friend Ben Grimm, his girlfriend Susan Storm, and Susan’s brother Johnny on an experimental rocket trip, but they’re bombarded by “cosmic rays.” There are six panels of claustrophobic, crimson-shaded agony: “My — my arms are heavy — too heavy — can’t move — too heavy — got to lie down — can’t move” is Ben’s panicked staccato.

They slam back into Earth and immediately find their situation has gotten even worse. Susan starts to turn invisible and screams as she looks at her disappearing flesh. Ben’s skin melts and expands until he resembles a misshapen pile of orange stones; he immediately blames Reed and tries to beat the tar out of him. Johnny calls his friends “monsters” before levitating and bursting into flame. Reed’s limbs stretch away from him like distended rubber, and he howls, “What am I doing? What happened to me? To all of us?” The characters seem trapped in a horror fable. Eventually, they calm down and decide to use their powers to help mankind — but as they do so, Lee’s dialogue has them tossing passive-aggressive taunts, and Kirby’s pencils show them bearing miserable expressions. The whole thing doesn’t feel like a traditional superhero comic; it’s more like a David Cronenberg movie or a booze-soaked fight at a Thanksgiving dinner. This mix of wild sci-fi invention and human drama continued in the ensuing monthly installments: One issue, the Four would save Earth by transmogrifying alien invaders into cows; just a few months later, they’d face eviction from their headquarters because they’d run out of rent money.

It’s hard to appreciate today just how radical a shift in tone the first Fantastic Four was. But there was another revolutionary aspect of the series, one hidden from the reader but unendingly controversial: It was the first superhero series to use the so-called “Marvel method.” To save time while writing a dozen or more comics at once, Lee had recently developed a thrifty alternative to writing out full scripts. He’d merely come up with a rough plot — ”as much as I can write in longhand on the side of one sheet of paper,” as he put it in a 1968 interview — talk that over with the artist, then make the artist go off and create the entire story from scratch. Every emotional beat, character interaction, and action sequence was now the responsibility of the guys drawing them, who until then had been accustomed to just drawing whatever a script told them to draw. Now it was the artists who built the narrative architecture, and the writers who did something more like buffing up: Once Lee got the artwork back, he’d interpret what he saw and cook up dialogue bubbles, narration, and sound effects. “Some artists, such as Jack Kirby, need no plot at all,” Lee said in that 1968 chat. “I mean, I’ll just say to Jack, ‘Let’s let the next villain be Dr. Doom.’ Or I may not even say that. He may tell me. And then he goes home and does it. He’s so good at plots, I’m sure he’s a thousand times better than I.”

The Marvel method gets a bad rap in the comics community these days because it allowed Lee to claim he’d written stories that were actually co-plotted by the artists, but at the time, it was an artistically fertile game-changer. The tyranny of full scripts was over, and artists were free to come up with graphic ideas that worked for them. “I realized that comics from a script was absolutely paralyzing and limiting,” says John Romita Sr., an artist who worked extensively with Lee in the ’60s and has remained a close friend ever since. “When you had the option of deciding how many panels you’d use, where to show everything, how you pace each page out, it’s the best thing in the world. Comics becomes a visual medium!”

“Even before the sales totals were in, we knew we had a major success because of the amount of enthusiastic fan mail,” Lee says in his new memoir, and Marvel feverishly fed this newfound demand. Over the ensuing months, Lee and Kirby cranked out stories about one eccentric superhero after another. Self-loathing scientist the Incredible Hulk, maimed war profiteer Iron Man, literal god Thor, and ostracized freaks the X-Men all appeared in the space of just two years. Lee had writing chores for as many as eight series at a time and was editor of all of them. That was an incredible burden, but also a creative opportunity: When Lee decided to have all these new characters periodically run into each other in their fictional New York City, he was able to keep that new shared universe straight in his head.

It’s difficult to overstate the significance of Lee’s invention of the idea of a comprehensive shared universe. It was a genius way to move product: If you wanted the full story of what was going on with your favorite characters, you had to buy series that starred other characters. But it was also a creative coup: Marvel was suddenly crafting a massive, unified story in which a reader could totally lose themselves. (It’s no wonder today’s movie studios are all rushing to follow the Marvel model and create their own shared universes filled with Jedis or raptors.)

Young people flocked to newsstands to pick up Marvel comics. College groups would write to Lee, begging him to come speak about the nature of comics art. Newspapers and magazines started writing profiles of Marvel — usually with Lee at their center. He did the talk-show circuit. Filmmakers Federico Fellini and Alain Resnais sought audiences with Lee to tell him how highly they regarded his work. Lee wasn’t a radical leftist, but he knew how to tap the Zeitgeist: He and Kirby created a hyperintelligent black hero, the Black Panther; their female characters were often pugilists, not just pinups; and stories would often depict youthful rebellion and protest sympathetically. Lee was a genius at making fans feel cared for, addressing Marvel’s “True Believers” directly in his delightful letters pages and in missives sent to a Lee-created fan club called the Merry Marvel Marching Society. By 1965, Marvel boasted that it was selling an estimated 35,000,000 comics a year — one comic for every five people in the United States. “He saved the comic-book industry,” says Michael Uslan, producer of the Batman films, comics writer, and historian. “He allowed comic books to grow up and find an older audience. And as we grow up, instead of leaving comic books, we stay with them for the rest of our lives. That’s an incredible thing.”

“What Stan did in the ’60s was really to go out there and evangelize, to be a P.T. Barnum or a Sol Hurok, a promoter of the fact that comics weren’t just a children’s medium and certainly not just a stupid children’s medium,” says longtime comics writer, executive, and historian Paul Levitz. “He seized on every bit of evidence that could be developed: the movie director, actor, the singer, the implied endorsement, the opportunity to talk on college campuses. He certainly enjoys the sound of his own voice and enjoys performing, but he’s really, really good at it.”

The version of that voice that made it into print was another game-changer. Prior to the Marvel revolution, the top superhero series were DC Comics’ tales of characters like Superman, Batman, and the Justice League — and the characters never talked like human beings. (“Green Lantern, the power ring — it’s glowing!” “That means somebody has stolen one of the objects I marked with an invisible aura! Let’s go!”) Lee’s characters used slang, told jokes, and sounded distinct from one another. His narration often broke the fourth wall. And in the comics’ letters pages, Lee spoke to readers like a close friend, directly stoking their enthusiasm and giving them a personal relationship with him. To pick one of hundreds upon hundreds of examples: In Avengers No. 12, there’s a letter from a Steve Lucero of Laramie, Wyoming, who wrote to “compliment you on all your Marvel mags,” say his mom was happy to see him reading so much, and end with a hope that “this letter wasn’t too long and boring.” Lee’s reply: “Aw, you know us, Stevey! No letter is ever boring when it’s flattering us! And be sure to tell your mom ‘hello’ from the guys in the bullpen!”

“This was coming at a time when the baby-boomers were teenagers,” says Lee biographer and comics journalist Tom Spurgeon. “If Stan hadn’t been doing those stories that were for teenagers and not kids, comics would have disappeared. DC was very much doing stories for people under 13, and he was going more for 18.” This is an important distinction, one that helps explain Lee’s significance, as well as his awkward place in current comics geekdom. When you’re a grown-up, you’re going to lump kids’ comics and teen comics in with one another as childish pap. But when you’re a teenager, the difference between the two is massive. In the ’60s, he who controlled the hearts of teens could control the marketplace.

Lee’s most important contribution might also have been his most exemplary case-study:Spider-Man. He swung onto Marvel’s pages in 1962 in a story drawn by a tremendously talented and camera-shy artist named Steve Ditko. In that first adventure, you can see Lee using his unique voice right away with some self-deprecating, fourth-wall-breaking narration: “Like costume heroes?” the first panel asks in thick black ink. “Confidentially, we in the comic mag business refer to them as ‘long underwear characters’! And, as you know, they’re a dime a dozen! But, we think you may find our Spiderman just a bit … different!” He was, indeed. The tale of nebbishy Peter Parker and the spider bite that gave him strength and stickiness is well known now. But it’s like listening to early Beatles singles: They sound dull today because their iconoclasm became a new template.

The story bucked convention in two key ways: The protagonist was a teenager (previously, teens were nearly always sidekicks), and he was prone to being a smart-aleck asshole. After showing off his newfound powers on TV and blowing off a bunch of admirers (“See my agent, boys! I’m busy!”), he blithely lets a criminal run past him and tells an astonished police officer, “Save your breath, buddy! I’ve got things to do!” Of course, the criminal then kills Peter’s uncle, leading him to realize that “with great power there must also come — great responsibility,” perhaps the nine most famous words Lee will ever write. That balance of unconventional humor and emotional agony had never been tried in comics before, and Lee and Ditko deployed it month after month in The Amazing Spider-Man. There was a fundamentally relatable message at the core of the series: No matter how strong you are, you can’t punch your personal flaws.

Speaking of which: Lee’s role in Spider-Man’s creation is the most disputed story of all. For decades, Lee took unequivocal full credit for the character concept, variously saying he was inspired by seeing a spider or remembering a ’30s pulp hero called the Spider. Ditko refuses all interviews, but if you mail a $40 check to a friend of his in Washington State, you can get a stack of Ditko-written manifestos saying Lee just came up with the name and that every other aspect was Ditko’s idea. In a 2001 pamphlet, he rails against the idea that Lee was the sole creator: “So for 30-plus years, the ‘one and only creator’ theme continued to pollute various publication outlets. The subjective and intrinsic mentalities continued their unquestioning, unchallenging, and self-blinding support of the non-validated claims.” (Ditko has a penchant for purple prose.) To make matters even more confusing, Kirby claimed he crafted every aspect of Spider-Man on his own before giving the project to Lee and Ditko.

There’s also the issue of how the artists were credited on an issue-by-issue basis — something far more provably damning for Lee. As Marvel’s popularity grew, he wisely chose to engage fans by giving specific credits at the front of each issue, something the fly-by-night comics industry had rarely bothered to do. But when readers saw “RUGGEDLY WRITTEN BY: STAN LEE, ROBUSTLY DRAWN BY: STEVE DITKO” or “SENSATIONAL STORY BY: STAN LEE, ASTONISHING ART BY: JACK KIRBY,” they were being profoundly misled. The mechanics of the Marvel method meant that, by any reasonable definition, his artists were actually authoring the stories with him. Their resentment grew.

So, though Lee gained the world, he lost the partners who helped him seize it. The principled and eccentric Ditko successfully lobbied to get plot credits in The Amazing Spider-Man but still felt underappreciated by Lee. The two stopped speaking and Ditko quit Marvel outright in 1966. That same year, Nat Freedland of the New York Herald Tribune’s magazine section (the predecessor publication to New York) stopped by to report an infamous feature story called “Super Heroes With Super Problems,” which took a hip New Journalism approach to describing the hot company. Hipness recognizes hipness, so Freedland focused almost entirely on Lee, “an ultra–Madison Avenue, rangy look-alike of Rex Harrison” who “dreamed up the ‘Marvel Age of Comics.’” But Freedland was cruel in his descriptions of Kirby, calling him “a middle-aged man with baggy eyes and a baggy Robert Hall–ish suit” and saying, “If you stood next to him on the subway, you would peg him for the assistant foreman in a girdle factory.”

“That article did enormous damage to Jack, personally and professionally,” recalls Evanier, who knew Kirby better than most. “It convinced Jack he couldn’t get the proper recognition there.” Kirby stayed put for a while (he’d later say he wanted to leave but had to earn money to support his family), but abandoned Marvel to work for DC in 1970. Almost right away, he wrote and drew a short story about a thinly veiled Lee analogue named Funky Flashman. Funky is a verbose fraud who orders around a Roy Thomas pastiche named Houseroy and constantly declares his own greatness without ever producing anything. “I know my words drive people into a frenzy of adoration!!” he insists. “Image is the thing, Houseroy!” Kirby’s anger was shared by other people in the industry who disapproved of Lee’s methods: A DC comic called Angel and the Apefeatured a comics editor named Stan Bragg, who asks a creator, “Why are you so ungrateful? When you write good stories and do good artwork, don’t I sign it?” A satirical series called Sick featured a strip in which comics editor Sam Me tells an artist to make some arduous revisions before reminding him, “And don’t forget to sign my name to it!”

Lee felt hurt by this kind of caricaturing, telling Thomas he couldn’t get why Kirby in particular would be so mean to him. But none of the criticisms shook Lee enough to get him to apologize. In fact, he seemed confused as to why his beloved artists departed. “He’d say, ‘I never fully understand why Jack or Steve left,’” Evanier says. “Steve’s reasons were pretty obvious, and so were Jack’s, and I’d explain them to Stan. He would nod. And then three months later he’d say, ‘Can you explain to me what Jack is upset about?’”

Lee remains maddeningly stubborn about Kirby and Ditko to this day. He sings their praises louder than anyone, saying they were the most tremendous collaborators a guy could ask for and that their art was museum-quality. But he refuses to admit he did them wrong, even as, in the past decade or so, he’s started billing himself as “co-creator” of Marvel’s core cast. Take, for example, this exchange with BBC host Jonathan Ross in a 2007 documentary about Steve Ditko:

“Do you, yourself, believe that he co-created it?” Ross asks, referring to Spider-Man.

Lee sighs lightly. A beat. “I’m willing to say so.”

“That’s not what I’m asking you —”

Lee cuts him off. “No, and that’s the best answer I can give you.” He goes on: “I really think the guy who dreams the thing up created it! You dream it up, and then you give it to anybody to draw it! I mean —”

“But if it had been drawn differently, it might not have been successful or a hit,” Ross counters.

“Then I would have created something that didn’t succeed,” Lee replies.

At the back of Comikaze’s main floor in the Los Angeles Convention Center, you find a row of black curtains below a massive sign that reads, “Stan Lee’s Mega Museum.” If Lee is doing an autograph session in there, it’s impossible to enter unless you’ve paid $80 in advance for his signature (for $25 more, you can get a certificate with a holographic sticker saying the signature is official). But when he’s off doing something else, you can walk through the aisles and see an odd array of objects, nearly all of them signed by Lee. One thing you don’t see there is any evidence of the dozens and dozens of superhero characters he’s made since he left Marvel’s daily writing trenches in the early 1970s.

The shift in Lee’s fortunes and reputation began in 1972. In that year, for the first time since he was a teenager, Stan found himself not writing comics every day. Marvel had new owners, and they wanted him to oversee the empire he’d been so instrumental in building. He was made president and publisher of Marvel Comics. He left the president position soon after, but stuck around as publisher and never returned to the writing trenches he’d spent his life toiling in.

He never found a truly comfortable new normal at Marvel. Right from the beginning, he didn’t quite know how an executive is supposed to act. Roy Thomas recalls an incident in which Lee had a minor quibble about the way a writer had done a bit of Thor dialogue, and cornered that writer in the hallway to address it. The writer, understandably, was terrified that one of his employer’s top men was criticizing him — and doing so out in the open, no less. “I said, ‘Stan, you’re the publisher!’” Thomas says. “‘You’re the guy who created this whole thing! You come down like a ton of bricks on him, they’re not gonna think this is just a little correction, they’ll think that it’s all over for them!’ It’s different when you do it as a publisher and people don’t have a lot of day-to-day interface with you.” The C-suite chafed Lee.

He would still occasionally dip his toe in the tide and write a comic or two, but they never garnered the kind of acclaim he’d received when he was cranking out nearly a dozen every month. Part of the problem was that Lee was a victim of his own success. He’d spent a decade lobbying for comics to be seen as more than kids’ stuff, and, as a result, comics became increasingly inappropriate for youngsters. And while the stories he’d turned out in his golden period were darker and weirder than what had come before, a decade later, they seemed timid by comparison — as did Lee himself. Conway wrote a Spider-Man story in which Peter Parker’s girlfriend is thrown off a bridge and dies, and though it was a bold and buzz-creating sensation, Lee broke Marvel ranks and denounced the decision to kill off a beloved and innocent figure. But that was the trend in comics from the mid-’70s, well into the early ’90s: tales in which death stalked at every corner and heroes became antiheroes. Lee put out stories about spacefaring philosopher the Silver Surfer, but the public was more into blood-soaked tales starring characters with names like the Punisher and Son of Satan. What’s more, the so-called “underground comix” scene of R. Crumb and his cohort was proving that the art world could take comics seriously — but only if the comics were about sex, drugs, and rock and roll instead of superheroes. Lee even tried to collaborate with some underground comix artists to make a Marvel comic featuring them, but that was a sales flop and only lasted five issues.

“Stan was pushing the limit of what his voice could do,” says Conway. “Some people, like a Frank Sinatra, can learn to phrase around a song so you don’t have to sing the notes you can’t sing anymore. But for comics, you can’t do that. Comics are a visceral, gut art form. You’re doing it because you absolutely have to do it, and there’s no reason to do it otherwise. And Stan didn’t have to do it.”

He also set his sights far beyond comics. He had Marvel’s owners put out a magazine called Celebrity that largely existed to get him in photos with movie stars. He did advertisements for Personna razors and Hathaway shirts (“When you create super-heros [sic], people expect you to look like one. I wear Hathaway shirts”). He even pitched an erotic comic strip to Playboy, starring characters with names like “High Priestess Clitanna” and “Lord Peckerton.” It was to be drawn by Romita, but the deal fell through: Romita believes he scuttled it when he told Lee, “I don’t wanna do stuff that I’m ashamed to show my grandchildren.”

Lee then aimed for Hollywood, moving to Los Angeles in 1980 to convince studios that his beloved superheroes could thrive onscreen. It was hard going, and Marvel’s owners at the time didn’t share his confidence about superhero fiction’s chances in live-action. “He was just a lone figure in the wilderness,” Spurgeon, the biographer, says. “He couldn’t take a paper out of his jacket pocket and work out a deal there with anybody. He was a PR and concepts guy.”

In that legendary interview with The Comics Journal, Kirby was even harsher. “I could never see Stan Lee as being creative,” Kirby said, and “I think Stan has a God complex,” and “I’ve never seen Stan Lee write anything,” and so on. Those words became gospel for a generation of cynical fans who had grown out of their childhood awe, and the Journal launched a kind of holy war on Lee, dedicating its October 1995 issue to scathingly critical essays and interviews about him. The irony was bittersweet: Lee had long campaigned to have comics be treated seriously as high art, and the Journal’s high-minded writing was proof that he’d been successful; but the generation of fans who saw comics as a legitimate medium also thought of him as a childish relic.

Lee claims he had a final reconciliation with Kirby at a comics convention shortly before Kirby died in 1994, but Evanier and Spurgeon say the interaction likely never happened.

Then a fork in the road appeared. In 1998, bankruptcy proceedings voided Lee’s contract with Marvel and, after some tense negotiations, he negotiated an extremely lucrative new agreement: an $810,000 annual salary just for being a figurehead, 50 percent of his base salary as an annual pension for his wife, and 10 percent of any profits Marvel would ever make off of movies and TV. He could have used the money to settle into easy elder-statesmanship, even if Marvel never took over Hollywood like we now know it would.

But Lee couldn’t stay out of the game, partly because a persuasive criminal made him an offer he couldn’t refuse. Lee had become friends with a genial professional fund-raiser named Peter Paul, and Paul found out Lee had a clause in his new contract that allowed him to make his own entertainment firm. “He said, ‘Hey, Stan, now you’re free! Lemme build a company,’” Lee gleefully recalled at the time. The company was called Stan Lee Media — SLM for short — and it was a complete disaster.

The plan was to put Lee’s creative genius to work on brand-new characters that he would own, and to push those properties out as comics, movies, toys, video games, and the buzzy new medium of animated “webisodes.” What’s more, there would be brand synergy with hot young entertainers like the Backstreet Boys and the Wu-Tang Clan (“Maybe, in our own way, we can turn them away from gangsta-rapping,” Lee said of the Wu). Lee cooked up one superhero after another: Thunderer! Oxblood! Imitatia! The Streak! Paul raised $1 million in seed money and projected annual revenue of $119 million within five years. It was, in other words, a classic example of a dot-com boondoggle.

Early on in the existence of SLM, Paul admitted to Lee that he had a bizarre and checkered past: He’d served time in federal prison after getting busted for cocaine possession and an attempt to defraud the Cuban government. Lee forgave him for this sin, but what he didn’t know was Paul had already embroiled him in another insane scheme: He was using the Stan Lee brand to rob SLM’s investors. Profits were being exaggerated, there were shady stock sales, and the SEC eventually swarmed SLM to bust Paul for fraud in 2001. He escaped to Brazil, only to be extradited and convicted. Lee was cleared of wrongdoing, but he was humiliated and swiftly severed all ties to SLM. Lee’s new comics-format memoir devotes exactly one panel to the SLM affair. “It ended badly,” a sullen-looking drawing of Lee says, “and the less said, the better.”

While SLM was in its death throes, Lee partnered with two of his friends — producer Gill Champion and lawyer Arthur Lieberman — to form a new venture: POW! Entertainment (short for Purveyors of Wonder!, exclamation point mandatory). Lee wasn’t destitute, but he needed money for legal fees: In addition to the SLM fallout, Lee claimed that Marvel had failed to honor the stipulation of his 1998 contract that called for him to receive a percentage of the company’s film and TV profits. The subsequent lawsuit was a surreal spectacle — like Colonel Sanders suing KFC, as one commentator put it at the time. Movies based on Lee’s co-creations had started to take off at the box office, with 2000’s X-Men and 2002’s Spider-Man, and Lee had made onscreen cameos in both. But his relationship with the company he built had become fraught.

According to historian Sean Howe, Marvel’s newly installed and notoriously prickly owner Ike Perlmutter despised Lee, resented paying him a pension, and had demanded that Marvel stop featuring the phrase “Stan Lee Presents” in issues’ credits pages. The legal battle lasted for three years, concluding with a settlement in 2005. Though the details are secret, Marvel appeared to have made a onetime $10 million payment to Lee. But his profit-sharing for film and TV was ended, just a few years before Marvel started to dominate the box office. If Marvel had kept up its end of the percentage deal, Lee would be making tens of millions of dollars for The Avengers, Guardians of the Galaxy, and the like. He just barely missed the boat.

While in town for Comikaze, I asked POW!’s publicists repeatedly if I could visit the company’s offices. I was only ever given silence or vague allusions to it being a possibility. Finally, as my trip was nearing its close, I decided to make a last-ditch effort and just show up at the address listed on Google Maps. As I was about to leave my hotel, one of the publicists wrote to inform me that I wouldn’t be allowed inside, but I figured it was worth a little peek. I took a bus to the nondescript Beverly Hills office building where POW! resides, tentatively sneaked up to the floor it’s on, and walked to the suite in question. All I found was a windowless wooden door, adorned only with a printout of the company logo. The printout was torn on one end and listing off at a haphazard angle. It felt like an apt metaphor.

Business has never been Lee’s forte, and his past missteps weigh heavily on him. His representatives declined to give me an interview despite more than a dozen attempts over the course of six months, but I was allowed to send a handful of questions via email. The only interesting response came when I asked him what he’d do differently if he could live his life all over again: “I’d have been a better businessman and attempted to gain a share of ownership of the characters I created.”

With POW!, he would. The problem was the characters. The firm’s first high-profile project was Stripperella, a cartoon with an accompanying comic book, both released in 2003. It was done in partnership with Pamela Anderson and men’s-interest TV network Spike, and it followed the titillating tussles of Erotica Jones, a ludicrously buxom woman who pole-dances by day and fights crime by night. It was a spiritual successor to that failed Playboy pitch, filled with ribald wordplay (episode titles included “You Only Lick Twice” and “The Curse of the WereBeaver”) and a tone that placed its tongue firmly in its cheek. Lee, apparently, wanted to push the envelope pretty far: “Stan wanted nudity,” Anderson tells me. “I didn’t.” It failed to find an audience, and though Anderson says she had a great time doing it and loves Lee, she couldn’t devote too much focus to it. There was never a second season.

For the rest of the decade, the company cranked out a lot of projects on a lot of different platforms, but very few of them managed to make an impact. There was a project released in children’s-book and direct-to-video movie format, Stan Lee’s Superhero Christmas. There was a direct-to-cable movie about a superpowered spy played by Jason Connery called Stan Lee’s Lightspeed. There was a reality show on the History Channel called Stan Lee’s Superhumans, in which Lee sent the show’s host off on adventures to find real people who can do unusual things like push needles through themselves or survive venomous snakebites. There was a truly bizarre partnership with the NHL in which Lee came up with superhero mascots for every team in the league. (They were all a little on-the-nose: The Florida Panthers’ hero was the Panther, the Toronto Maple Leafs got a tree-powered crusader named the Maple Leaf, and so on.) And the underwhelming releases kept rolling out: a mobile game called Stan Lee’s Verticus, a comics/cartoon project targeted at the Indian market called Chakra: The Invincible, and so on.

But there’s a crucial thing you have to know about how Lee approaches these products: He’s not an absentee landlord. He’s always substantially involved in the projects bearing his name, in part because he isn’t happy just playing the role of showman — he wants the airtight creative credit that, in recent decades, has come into question, thanks to Ditko and Kirby. So while Lee’s brand is slapped on so many products that you might imagine he’s become like Krusty the Klown or the members of KISS, letting any random product get the Stan Lee seal of approval for the right price, this is very much not the case.

Perhaps the most arresting example comes from veteran superhero-comics writer Mark Waid. He was in charge of managing a line of three comics series based on story and character concepts from Lee and executed by respected industry talent. Waid tells of meeting with Lee to show him a rough draft of an upcoming issue, which Lee read with consternation. “He got to end of it and said, ‘I can’t have my name on this,’ and my heart sank,” he recalls. Luckily, Waid made revisions, and Lee enthusiastically endorsed the finished product — but Waid has never forgotten Lee’s unwillingness to brand something he didn’t like.

Of course, none of this is the most famous stuff Lee has done in the past 16 years. The most famous stuff is the cameos. Going back to the years before Marvel movies took off, he began appearing in Marvel-based TV shows and Saturday-morning cartoons about his co-creations, and he’s remained visible onscreen ever since. In nearly every movie based on a Marvel comic, Lee briefly appears in a zany fashion, playing a mailman, a strip-club owner, a drunk war veteran — that sort of thing. He gets to attend the premieres and do interviews about what he was thinking when he created the characters that have made it to the big screen. He gets executive-producer and co-creator credits on them. Romita says these connections to the Marvel movies are huge for Lee because fame outside the eternally disdained world of comics has always been one of the man’s ultimate goals. “If there were never any successful Marvel movies, Stan would’ve been gone, he would’ve retired,” he says. “It changed everything. It legitimized it. It satisfied him.”

That may be true, but he’s not so satisfied that he’s willing to slow down. “Y’know, most people, when they retire, they say, ‘At last, I’ll have a chance to do what I’ve always wanted to do,’” Lee said in a CNN interview a few years ago. “But I’m doing what I’ve always wanted to do! I’m working with artists, writers, with directors. I’m working on creative things. I’m having fun! I mean, don’t punish me by making me retire.”

Near the end of the Dragons vs. Pandas press conference, Lee abruptly starts talking about the guiding philosophy that drives his work. “When I used to go to bookstores, the only books I would pick out were ones that looked like they were different than anything I normally read,” he says. “We have always tried to come up with things that nobody else is doing. Now, of course, you can do things that nobody else is doing, and the reason nobody is doing it is because they’re stupid ideas.”

Hearing Lee speak at the convention, my mind was cast back to the first and only time we’ve had a one-on-one interaction. It was at the 1998 Wizard World Chicago Comic-Con, when I was 12 years old. I’m honestly not sure when or how I first became aware of Lee — he just seemed omnipresent for anyone who cared about superheroes — but by that age, I was a true believer in his mythology. So I waited in line for nearly an hour to get his signature on a tattered copy of Fantastic Four No. 47. When I finally reached the front of the line, it was like I was in the presence of God. I asked someone to take a photo of the two of us on a disposable camera. The flash went off and he crowed, “You’ve immortalized me!” I could tell it was a joke, but that word, immortal, lingered in my ears. Because that’s just how he’d always seemed to me: somehow above the rest of us, watching with paternal awe at the world he’d made.

Before reporting this article, I’d never had to come up with my own estimation of what Lee means to the world, much less to me, and I had whiplash-inducing changes of heart while reading about him. But his greatest sin was probably overreach: He accomplished so much, but he wanted to claim more; he was a brilliant craftsman in his prime, but he kept creating when he might have been better suited to retirement. Like the superheroes whose stories he wrote, he is a flawed being, capable of pettiness and hubris. But he’s put too much love and joy into the world — into my world — for me to even come close to deriding him.

This puts me in league with the friends and colleagues of his that I interviewed. We understand that he erred, but that only forces us to try harder to understand him and see the man in full. “I think he’ll be remembered as the guy who gave the world the Marvel universe,” says Thomas. “I know various others of us — Jack and Steve — were very important in that. But without Stan Lee, there is no Marvel universe. He’s the one who had the vision.”

In one of his final Comikaze appearances, Lee is onstage having a chat with some younger comics pros, and one of them — Marc Silvestri — tries to rib Lee about being so old that he probably hung out with Moses. Lee seems to take it in stride (or doesn’t hear it, since his hearing isn’t what it used to be), but Silvestri is getting it all wrong. Lee, in a way, is a kind of Moses: a charismatic leader who saved a genre and led his acolytes through the harsh world of mainstream entertainment for decades — only to see his people finally enter the promised land of Hollywood billions without him. So now he stands on the border, smiling and welcoming people in, but always making sure to give them a little tap on the shoulder before saying, Tell ya what, True Believer — if you like this, you’re gonna love the brand-new promised land I’m building just around the corner …

*A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the memoir was ghostwritten.