Great Central Railway, Loughborough June 2016

Further evidence of the importance of coffee bars in the radical culture of the 1960s. (From the New York Times.)

In the summer of 1967, Fred Gardner arrived in San Francisco with the Vietnam War weighing heavily on his mind. Gardner was 25 years old, a Harvard graduate and a freelance journalist for a number of major publications. He was attracted to Northern California’s mix of counterculture and radical politics, and hoped to become more actively involved in the movement to end the war. He was particularly interested in the revolutionary potential of American servicemen and couldn’t understand why antiwar activists and organisers weren’t paying more attention to such a powerful group of potential allies.

Ever since completing a two-year stint in the Army Reserves in 1965, Gardner had been closely watching the increasing instances of military insubordination, resistance and outright refusal that were accompanying the war’s escalation. From the case of the Fort Hood Three — G.I.s arrested in 1966 for publicly declaring their opposition to the war and refusal to deploy — to the case of Howard Levy, an Army dermatologist who refused his assignment to provide medical training for Special Forces troops headed to Vietnam, it was clear that the Army was fast becoming the central site of an unprecedented uprising. By 1967, the “G.I. movement” was capturing national headlines.

And it wasn’t just the war that was aggravating American servicemen. The military’s pervasive racial discrimination — unequal opportunities for promotion, unfair housing practices, persistent harassment and abuse — fueled increasing outrage among black G.I.s as the war progressed. Influenced by the civil rights and black liberation movements, black soldiers participated in widespread and diverse acts of resistance throughout the Vietnam era. Racial tensions were particularly high in the Army, where a vast majority of draftees were being sent, and where evasion, desertion and insubordination rates among black G.I.s exploded in the war’s later years. An antiwar movement in the military was beginning to take shape, with black soldiers often its vanguard.

Antiwar veterans protest at the Federal Building in Seattle, September 1968. CreditFred Lonidier

As Gardner sat in the radical coffeehouses of San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood that summer, he thought about the explosive power of servicemen turning against the war and wondered how that power could be supported and nurtured by the civilian antiwar movement. Most of all, he wanted to find a way to reach out to disaffected young G.I.s, to show them that there was a whole community of antiwar activists and organizers who were on their side. He finally settled on an idea: opening a network of youth-culture-oriented coffeehouses, just like the ones in North Beach, in towns outside military bases around the country.

In January 1968 he did just that, travelling with a fellow activist, Donna Mickleson, to Columbia, S.C., home of Fort Jackson, one of the Army’s largest training bases and the crown jewel of the state’s many military installations. The UFO coffeehouse, decorated with rock ’n’ roll posters donated from the San Francisco promoter Bill Graham, quickly became a popular hangout for G.I.s — and a target of significant hostility from military officials, city authorities and outraged local citizens (“It’s a sore spot in our craw,” a Columbia official said.) The coffeehouse was located just off base, out of the military’s reach but close enough for soldiers to visit during their free time — places where active-duty servicemen, veterans and civilian activists could meet to plan demonstrations, publish underground newspapers and work to build the nascent peace movement within the military.

By the summer of 1968, major antiwar organizations took notice of the controversy the UFO was stirring up in Columbia and initiated a “Summer of Support” to organize funds for more coffeehouse projects around the country. In ensuing years, more than 25 “G.I. coffeehouses” opened up near military bases in the United States and at a number of bases overseas.

Over the course of six years, the coffeehouse network would play a central role in some of the G.I. movement’s most significant actions. At the Oleo Strut coffeehouse in Killeen, Tex., local staff and G.I.s mobilized to support the Fort Hood 43 — a large group of black soldiers who were arrested at a meeting to discuss their refusal to deploy for riot control duty at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. A black veteran present at the meeting described its mood: “A lot of black G.I.s knew what the thing was going to be about and they weren’t going to go and fight their own people.” Army authorities were caught off guard by the publicity the coffeehouse brought to the case, and began to examine their strategies for dealing with political expression among the ranks.

When eight black G.I.s, each of them leaders of the group G.I.s United Against the War in Vietnam, were arrested in 1969 for holding an illegal demonstration at Fort Jackson, the UFO coffeehouse served as a local operations center, drumming up funds for lawyers and promoting the “Fort Jackson Eight” story to the national media. After G.I. and civilian activists created intense public pressure, officials quietly dropped all charges, signaling a shift in how the military would respond to soldiers expressing dissent.

During its brief lifetime, the G.I. coffeehouse network was subjected to attacks from all sides — investigated by the F.B.I. and congressional committees, infiltrated by law enforcement, harassed by military authorities and, in a number of startling cases, terrorized by local vigilantes. In 1970, at the Fort Dix coffeehouse project in Wrightstown, N.J., G.I.s and civilians were celebrating Valentine’s Day when a live grenade flew in through an open door; it exploded, seriously injuring two Fort Dix soldiers and a civilian. Another popular coffeehouse, the Covered Wagon in Mountain Home, Idaho (near a major Air Force base), was a frequent target of harassment by outraged locals, who finally burned it to the ground.

Though their numbers dwindled as the war drew to a close in the mid-1970s, G.I. coffeehouses left an indelible mark on the Vietnam era. While popular mythology often places the antiwar movement at odds with American troops, the history of G.I. coffeehouses, and the G.I. movement of which they were a part, paints a very different picture. Over the course of the war, thousands of military service members from every branch — active-duty G.I.s, veterans, nurses and even officers — expressed their opposition to American policy in Vietnam. They joined forces with civilian antiwar organizations that, particularly after 1968, focused significant energy and resources on developing social and political bonds with American service members. Hoping to build the resistance that was already taking shape in the Army, activists at G.I. coffeehouses worked directly with service members on hundreds of political projects and demonstrations, despite relentless government surveillance, infiltration and harassment.

The unprecedented eruption of resistance and activism by American troops is critical to understanding the history of the Vietnam War. The G.I. movement and related phenomenon created a significant crisis for the American military, which feared exactly the kind of alliance between civilians and soldiers that Fred Gardner had in mind when he opened the first G.I. coffeehouse in 1968. Despite the extraordinary political and cultural impact that dissenting soldiers made throughout the Vietnam era, their voices have been nearly erased from history, replaced by a stereotypical image of loyal, patriotic soldiers antagonized and spat upon by ungrateful antiwar activists. In the decades since the war’s end, countless Hollywood movies, books, political speeches and celebrated documentaries have repeated this image, obscuring the war’s deep unpopularity among the ranks and the countless ways that American troops expressed their opposition.

This historical erasure serves a distinct purpose, casting dissent — from wearing an antiwar T-shirt to kneeling during the national anthem — as inherently disrespectful, even abusive, to American soldiers. A fuller reckoning with the era’s history would begin by acknowledging the countless G.I.s and civilians who stood together against the war. G.I. coffeehouses are a vital window onto this history, showing us places where men and women came together to share their common revulsion at the war in Vietnam, and to begin organizing a collective effort to make it stop.

“The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man is a 1962 book by Marshall McLuhan, in which the author analyzes the effects of mass media, especially the printing press, on European culture and human consciousness. It popularized the term global village, which refers to the idea that mass communication allows a village-like mindset to apply to the entire world; and Gutenberg Galaxy, which we may regard today to refer to the accumulated body of recorded works of human art and knowledge, especially books. McLuhan studies the emergence of what he calls Gutenberg Man, the subject produced by the change of consciousness wrought by the advent of the printed book. Apropos of his axiom, ‘The medium is the message,’ McLuhan argues that technologies are not simply inventions which people employ but are the means by which people are re-invented. The invention of

View original post 215 more words

Bob Hyde (1927-73) studied and then taught at St. Martin’s; from the mid-sixties until his death he was a senior lecturer at Wimbledon School of Art and lecturer at the Royal College of Art, where he helped establish the Environmental Media Degree with Sir Hugh Casson. In 1966, Bob devised and directed a ballet for ITV involving two dancers and projected images and in 1969 he designed Play Orbit, an exhibition organised jointly by the ICA and the Welsh Arts Council for the Royal National Eisteddfod of Wales. This exhibition invited one hundred British artists to create a toy or game.

Through his photography, Bob captured London and Britain in fragmentary form, creating work justifiably comparable in quality to that of Saul Leiter.

I love to find a good Paris photo story that I haven’t seen before, and this one that I found buried in Life magazine’s archives is a quite a treat. Veteran photographer for the magazine Loomis Dean followed a group of young students in 1961, getting an intimate peek into their lives as they pursued the bohemian dream in mid-century Paris.

And you know what? It doesn’t seem like much has changed. Clicking through, I noticed the routines didn’t seem so different from the Paris I’ve come to know today. Whether you start out in a tiny attic room or student dorms, throw yourself into the café culture or lose yourself in art museums, Paris is more recogniseable than ever in this photo story from decades past…

Actual photo caption: “Student with a hangover”.

A college dormitory at number 57 Rue Lacépède in the 5th arrondissement (Latin Quarter).

There is still a café under this building called La Contrescarpe (see it here on Google earth).

A student looking through his music.

Students studying in a park.

Art students visiting a gallery.

Strolling down the Seine…

Art students “picnicking” with their models…

All photos (c) LIFE

This is a video of my talk at BRLSI in July. It’s not great quality but you get the whole thing! I originally put it on YouTube but it got blocked because of my use of two Bob Dylan songs. This was a bit disappointing but I have decided to upload it here instead. I hope Bob won’t mind too much, he always seemed to understand the true value of copyright theft and plagiarism!

Me? I’m having trouble with the Tombstone Blues!

Friday 3rd and Saturday 4th of March 2017 I attended a conference at DMU, Leicester about film maker Peter Whitehead, and celebrating the donation of his archive to the University.

I found out about it late but am really glad I went. There were some excellent talks that brought new light to the meaning and relevance of the 1960s Counterculture, and other aspects of the Swinging 60s, and also a sublime showing of Whitehead’s Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London on the big screen at Phoenix Square Cinema, Leicester. It was almost like watching a different film to the one I have only previously seen on YouTube.

This is a fascinating view of what was happening at the height of what is now seen as the first great flowering of the Counterculture. It is not uncritical though and the seeds of it’s decline can be seen in the interviews of contemporary stars like Julie Christie, Michael Caine and David Hockney. There is almost a sense of impending loss, and also a critique of it’s superficiality and materialism.

The film is really a response to Time Magazine’s famous article about Swinging London that shifted American’s ‘must visit’ tourist location from Paris to London. After a brilliant start with footage from the UFO Club accompanied by a great version of Interstellar Overdrive by Pink Floyd, Michael Caine bizarrely announces that “…it all started with the loss of the British Empire….”

There is no narrative as such but a series of Chapters that are linked by the time and place, and a general sense of bewilderment by the participants. Following some amazing footage of the Rolling Stones live in Ireland Mick Jagger comes across as a slightly lost , petulant school boy trying to make sense of it all “… they don’t like violence but they themselves are violent which doesn’t seem to make sense…”. Yes okay Mick, thanks for that, you sound just like my mother. Julie Christie, who looks absolutely stunning, bemoans the fact that she is totally superficial and has nothing to say “… everything’s happening to me and I’m not happening to anything…am I allowed to talk?…”. David Hockney is not impressed by ‘Swinging London’ at all and prefers New York and California. The bars stay open til 2 a.m. and the drinks are cheaper and he can meet ordinary people in the clubs, unlike London which is overpriced and exclusive. To be fair though, David Hockney has been moaning about something for most of his life, quite often about not being allowed to smoke cigarettes wherever he wants! He is very amusing though. When Julie Christie smokes a cigarette in the film she doesn’t look like she quite knows what to do with it. Vanessa Redgrave, on the other hand, exudes confidence and political commitment and sings a capella and lectures the audience, a bit like an over-confident trainee teacher.

Andrew Loog Oldham is the stereotype of a cynical, Svengali-like pop manager who talks about how he ‘invented’ the Rolling Stones image as the ‘bad boys’ of pop, which, in fact, they quite obviously are not. He revels in his lack of knowledge but obviously believes he can do anything he wants “… I might get into politics someday..or films” he says. In some ways, this is quite a refreshing and confident attitude. Nevertheless, he never did get into either politics or films which is probably just as well as I am sure he would have joined the ranks of the Thatcherites and done something really terrible like close down the NHS or sell the whole of England to Disneyworld. The film ends where it began with some amazing footage of dancers at the UFO Club and the music of Pink Floyd. A truly remarkable film! There is a real sense of dynamism and change. The way the music accompanies the live performances of the Stones is inspired especially with the song Lady Jane. Whitehead doesn’t bother about synchronicity and blends unrelated recordings with live footage. Have You Seen Your Mother Baby (Standing in the Shadows), a surprisingly dark and seemingly uncommercial recording (even though it was a top ten hit), it’s not unlike the Velvet Underground, plays while the band and audience go wild and Lady Jane introduces a strange and eerie sense of calm.

The rest of the conference passed quickly. It took place over two days but the papers delivered were so fascinating that I never lost interest the whole time I was there. This has got to be a first for me, my attention can easily wander! I usually have alternative activities at hand in case I get bored! Didn’t need them this time! There were a wide range of themes that dealt with the 60s with some, but not all, relating to the work of Peter Whitehead

Adrian Smith discussed the interesting sub genre The Love Business: European Prostitution Drama as British Popular Entertainment. This dealt with the film distributors who were showing European films, many of which had a serious sub-text, as soft porn films to a British audience. There are some echoes of this theme in a recent Channel 4 series Magnifica 70 that deals with film and censorship in Brazil in 1970. Worryingly, this is about a right wing dictatorship in Brazil but could just as easily be about censorship and social control in Britain in the 1960s. Definitely worth a look.

Richard Farmar looked at the bizarre film The Touchables and Melanie Williams gave an interesting account of the film maker David Hart. She talked about the “Right-wing Counterculture” which to some would be a contradiction in terms. The majority of countercultural participants were either “left wing” or perhaps “apolitical” but she made a very good argument about how many issues, like women’s lib or gay rights, could belong to either the left or right. She pointed out how politician and journalist Jonathon Aitken started as a countercultural figure in the 1960s but ended up as a cabinet minister in the Conservative Government of the 1980s (before he ended up in jail, that is!). I have investigated elements of right wing attitudes in my essay The Decline of the 1960s Counterculture and the Rise of Thatcherism in which I look at libertarianism and other aspects of the counterculture in the 1980s such as sexual freedom, drug taking and “alternative” businesses such as Virgin and Gap.

Caroline Langhorst gave an interesting talk on three lesser known films of the 1960s all of which are critical of the optimism and the joie de vivre of the period. These are Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London, Privilege (starring Manfred Mann singer Paul Jones) and Herostratus (featuring a young Helen Mirren).

Both Privilege and, especially, Herostratus are relatively unknown films. Privilege had a cinema release in the 1960s (I actually saw it) but I believe Herostratus was virtually lost, although there is a copy now on Blu-ray (which I have yet to see). There are some clips of it on YouTube which are quite intriguing. Personally, I feel that the films that really define and critique the era, especially in terms of pop music and the counterculture, are Easy Rider, Performance (featuring Mick Jagger) and, of course, Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London. What becomes generally apparent is the mainstream media’s inability to really understand what is going on during this period. Their attempt to commercialise the movement in films of the time often produced a cliched view of pop culture and society that, for some, defines what the 1960s are about but is actually a ridiculous fiction.

There were some interesting talks about feminism in the 1960s. Alissa Clark investigated Peter Whitehead and Niki de Saint-Phalle’s collaberation Daddy. In 1972, Saint Phalle shot footage for this surreal horror film about a deeply troubled father-daughter, love-hate relationship. She was an artist, sculptor and film maker who made quite an impact on the avant garde scene from the 1940s onwards.

There was also a passionate and forceful account of radical filmmaker and theatremaker Jane Arden who I had actually not heard of before. In 1970, Arden formed the radical feminist theatre group Holocaust and then wrote the play A New Communion for Freaks, Prophets and Witches. The play would later be adapted for the screen as The Other Side of the Underneath (1972). Arden directed the film and appeared in it uncredited; screenings at film festivals, including the 1972 London Film Festival, caused a considerable stir. The film depicts a woman’s mental breakdown and rebirth in scenes at times violent and highly shocking; the writer and critic George Melly described it as “a most illuminating season in Hell”, while the BBC Radio journalist David Will declared the film to be “a major breakthrough for the British cinema”. Interesting stuff!

Stephen Glynn gave an entertaining look at Whitehead’s films of the Rolling Stones including the iconic promotional film for the song We Love You and Steve Chibnall showed us what the 1960s Counterculture was like in a provincial city, namely Leicester! Well, I should know because I was there, but he managed to come out with facts that I knew nothing about. For example, how the local paper The Leicester Mercury led a campaign to close down the late night clubs and coffee bars that proliferated at the time. Do You Know What Your Children Are Up To While You Sleep? screamed the headlines. My favourite band Legay complained that they had hardly anywhere left to play and were moving to London! I am shocked and stunned by these revelations!

Jimi Hendrix at the Leicester Art College Hawthorn Building. Local rock and roll band Warlock ended up doing the support spot.

Richard Dacre gave an entertaining account of the Counterculture and Peter Whitehead at the Royal Albert Hall. Apparently, after Wholly Communion, poetry performances were banned at the hall for more than 20 years! Hilarious. I am looking forward to the Whitehead inspired festival at the RAH later on this year!

Source: Camille Paglia on the Iconic Cover of Patti Smith’s Horses | Literary Hub

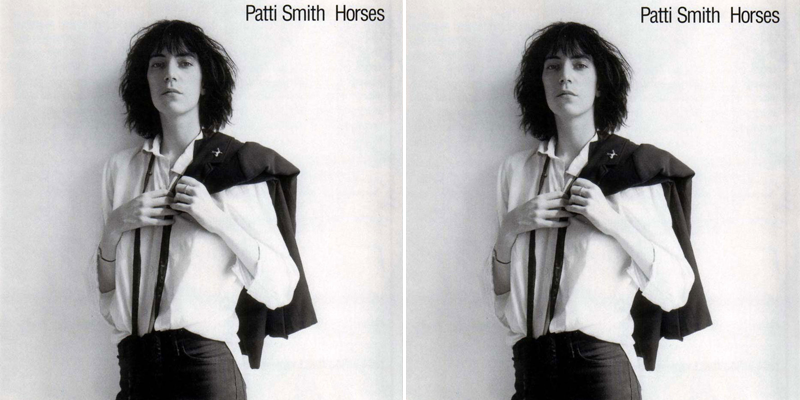

In 1975, Arista Records released Horses, the first rock album by New York bohemian poet Patti Smith. The stark cover photo, taken by someone named Robert Mapplethorpe, was devastatingly original. It was the most electrifying image I had ever seen of a woman of my generation. Now, two decades later, I think that it ranks in art history among a half-dozen supreme images of modern woman since the French Revolution.

I was then teaching at my first job in Vermont and turning my Yale doctoral dissertation, Sexual Personae, into a book. The Horses album cover immediately went up on my living-room wall, as if it were a holy icon. Mapplethorpe’s portrait of Patti Smith symbolized for me not only women’s new liberation but the fusion of high art and popular culture that I was searching for in my own work.

From its rebirth in the late 1960s, the organized women’s movement had been overwhelmingly hostile to rock music, which it called sexist. Patti Smith’s sudden national debut galvanized me with the hope (later proved futile) that hard rock, the revolutionary voice of the counterculture, would also be endorsed by feminism.

Smith herself emerged not from the women’s movement but from the artistic avant-garde as well as the decadent sexual underground, into which her friend and lover Mapplethorpe would plunge ever more deeply after their breakup.

Unlike many feminists, the bisexual Smith did not base her rebellion on a wholesale rejection of men. As an artist, she paid due homage to major male progenitors; she wasn’t interested in neglected foremothers or a second-rate female canon. In Mapplethorpe’s half-transvestite picture, she invokes her primary influences, from Charles Baudelaire and Frank Sinatra to Bob Dylan and Keith Richards, the tormented genius of the Rolling Stones who was her idol and mine.

Before Patti Smith, women in rock had presented themselves in conventional formulas of folk singer, blues shouter, or motorcycle chick. As this photo shows, Smith’s persona was brand new. She was the first to claim both vision and authority, in the dangerously Dionysian style of another poet, Jim Morrison, lead singer of the Doors. Furthermore, in the competitive field of album-cover design inaugurated in 1964 with Meet the Beatles(the musicians’ dramatically shaded faces are recalled here), no female rocker had ever dominated an image in this aggressive, uncompromising way.

The Mapplethorpe photo synthesizes my passions and world-view. Shot in steely high contrast against an icy white wall, it unites austere European art films with the glamorous, ever-maligned high-fashion magazines. Rumpled, tattered, unkempt, hirsute, Smith defies the rules of femininity. Soulful, haggard and emaciated yet raffish, swaggering and seductive, she is mad saint, ephebe, dandy and troubadour, a complex woman alone and outward bound for culture war.

Books reviews with the occasional interview thrown in for good measure

The art we all forgot, and rightly so.

Words for the mind, body and spirit

Classic Rock: More than meets the eye... and ear!

a group of singer/songwriters based in Leicestershire U.K.

Vanlife 4x4 | Adventure Motorhome Travel

It's what life throws at you and sometimes quite unexpectedly

Our adventures in Boris our motorhome

He not busy being born, is busy dying.

A collection of posts from Kenny Wilson's Blog at kennywilson.org

parisian.swing@outlook.com 0782 564 0991

Uncovering the silent era

Good time Scottish Ceilidh and Folk Dance Band

07825640991 kenny.wilson@outlook.com

0782 564 0991 kenny.wilson@outlook.com

A food and drink blog for Leicestershire

Gathering TV Dramas from around the World