Good interview and article about A.J. Weberman by David Samuels of the Tablet.

Source: Q&A: A.J. Weberman on Dylan, Lennon, Garbage, New York, and the JDL – Tablet Magazine

Alan Weberman is a stone cold meshugganeh. He is by no means a reliable news source. Yet, by the same token, the legalese that these days must precede any printed record of the former Yippie, drug dealer, JDO activist, and pioneering garbologist’s nonstop provocations should not be taken as evidence that Weberman is somehow innately any less truthful than the celebrities, political figures, and power structures that he delighted in tweaking, torturing, and maligning for the past half-century. Weberman is no more or less corrosive than he always was, and politicians and rock stars are no more honest.

What’s changed, in the meanwhile, is us. We don’t see the point of Webermans anymore. They’re too abrasive. Or maybe, we are all Webermans now, thanks to the Internet, which flushed away the grittiness of a true oppositional culture down the social media toilet bowl. Thanks to Google, Facebook, and Twitter, there is no longer anything thrilling or shocking about calling celebrities bad names and going through their garbage. Or maybe it’s because famous people have more money, and better lawyers. Or because what’s left of the press is run by Ivy League conformist-types who are eager to maintain the pure ivory of their permanent records and are very anxious about keeping up institutional appearances, which are the only real form of capital they have, because the press is broke, which is a fool-proof recipe for boring.

If it helps, you can think of Weberman as a bullet-headed human keyhole into the oppositional culture that New York City nurtured in the bad old days, before Giuliani and Bloomberg cleaned the place up and turned it into one big dormitory for knowledge workers who were good with numbers and would die before eating at the wrong restaurant or sending their kids to the wrong preschool. Everything that was wrong about the old New York is right about Weberman, and everything that is right about the new New York is wrong about Weberman. So, like most things in life, it depends on your angle. Without Weberman, the world will become an even colder and less hospitable place for weirdos, which is something that I oppose.

I met Alan Weberman in his high-rise apartment, which is located in the upper part of the Upper East Side and offers a spectacular view of Queens. Through a haze of smoke, he offered me some of his memories, while being interrupted by the incessant demands of an ill-mannered bulldog, who is clearly the main focus of his affections. An edited transcript of our conversation was then redacted by a lawyer. I put the lawyer’s version aside, as I wrestled with the question of whether a lawyered version of Weberman was even worth publishing.

After an appropriate period of prayerful reflection, which lasted over a year, I have decided that it is important to hear Weberman speak about Bob Dylan, John Lennon, Meir Kahane, being a drug dealer, and some of his other pet subjects. It’s good to remember that being Jewish once meant being half-crazy, in addition to being neurotic and annoying. Anyone who wants to hear a recording of Weberman talking to Bob Dylan on the telephone can click here.

Where did your obsessive focus come from? Were you that way as a kid?

It started when I was in Washington, D.C. on Nov. 22, 1973, as part of an organized demonstration to find out who stole John F. Kennedy’s brain from the National Archives. You know, because the brain was missing. A New York Times reporter came across that. There was an article recently that some people say RFK took it.

So, we had this demonstration, and this guy Bernard Fensterwald was having a conference on the same day. I’d gotten vibes from working with Fensterwald that there was more to him than really met the eye. So, I’d been working all week, not smoking pot, putting up posters, handing out leaflets all over D.C. Then I came back and gave a little speech at Fensterwald’s conference.

Then I met this girl who was working for Fensterwald, and I says, “Let’s get high,” you know. So we started, I had a little hash, but it was Georgetown University, and these nuns were coming in and out. And so I said let’s go back to your dorm room so we went back to her dorm room, getting high and listening to rock and roll. And then somebody starts yelling from downstairs. It’s Steven Soter, you know Carl Sagan’s sidekick. And he shows me these pictures of the tramps who were picked up an hour after the assassination in a freight car you know behind the Texas schoolbook depository. So, you know so one of them looks like, says oh I thought this one was Frank Sturges, but Bernard Fensterwald said he went down to D.C. to Dallas and did a fucking study and it wasn’t the guy.

And I says, “You believe Fensterwald man? Fensterwald’s probably working for the CIA.” I looked at the tramp shots and I says, “Hmm, one of them looks like Howard Hunt, one of them looks like Frank Sturgis, and the other one looks like this guy who I rented a room to when I was going to Michigan State before I got expelled for dealing pot.” So I says, “Wait a minute, how can one guy, one tramp, can look like Sturgis, the other looked like Hunt, they’re both Nixon’s plumbers in Watergate?” Howard Hunt was involved in Bay of Pigs, and Frank Sturgis was involved with every goddamn thing imaginable.

So, I went to the National Archives, and that’s when I started speed-reading documents, and I read every document in the National Archives about the Kennedy assassination. Then I hooked up with this guy Mike Canfield, and Canfield convinced Congressman Gonzalez to introduce a bill to investigate the Kennedy assassination. And that’s how the House Select Committee on Assassinations was formed.

Did you ever read Norman Mailer’s novel Harlot’s Ghost?

No. I went through his garbage, though.

What did you find?

Betting slips.

Haha.

He’s a chicken shit, though. I was there going through his garbage and he came out of his house in Brooklyn Heights and I expected a big confrontation. But I was wearing a trench coat, so he must have thought I was a Fed or something. He just moved along.

I lived on that block, just up the hill from that big Jehovah’s Witness “Watchtower” building. Do you think Dylan was inspired to write “All Along the Watchtower” because of his view of that sign from downtown Manhattan?

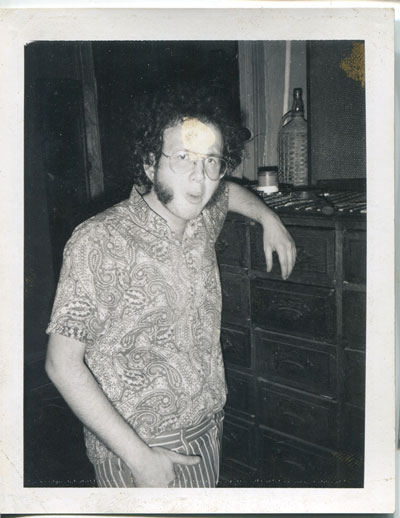

(Photo courtesy of A.J. Weberman)

No, no. All along the watchtower, princes kept the view, while all the women came and went, it’s about his career. Before, when I was at a very primitive stage of Dylanology, I thought the wind began to howl meant Dylan, the wind, like blowing in the wind, began to howl, like Ginsberg’s poem “Howl.” So, I went and asked Ginsberg about it. He comes to the door naked. He says, “No, Weberman no, no.”

But he would ask me for advice. He got mugged a lot, and he wanted to know what to do.

He is a human being.

You know, he fucked around with needles and he got fucking hepatitis. And then he finally got some money.

Why did everybody love the needle so much back then?

Don’t ask me. I didn’t mess with needles. But it’s just a very pleasurable thing, apparently. And when I knew Lennon, he was an addict. See the way he looks at the end of his life: He’s skinny, he’s emaciated. Him and Yoko, time and time again, they didn’t have clothes on. I would follow him into the fucking bathroom and watch him take a piss. You know, what difference did it make, he was nude anyway.

I feel like gestures that seemed perverse and counter-cultural when you made them first back in the day, like digging through Bob Dylan’s garbage, have become widely shared social instincts. In a way, garbage-ology is the soul of the Internet.

You know, the term garbologist existed—in Australian, it meant a garbage collector—but there was no garbology, which is the study of garbage. So, I invented the word “garbology.” It’s come to mean studying garbage to see what you can know, to increase recycling and understand socioeconomic divides and this and that. I did it just to spy on Dylan, essentially.

I’ve read some of the stuff you’ve written about your purported—and in some cases, recorded—phone conversations with Bob Dylan, which are hilarious. Why do you think he kept talking to you?

Well, I brought my Dylan class over to his house on a field trip. And he came out and he says, “Al, whatchu bringing all these people around for?” So I says, “Oh, it’s a field trip for my Dylanology class. But actually it’s a demonstration against all you’ve come to represent.” You know, and so it went. He rolled up his sleeves and he says, “Look, I’m not a junkie.”

Then Dylan called me later on, when I got back to Sixth and Bleecker, and he says “Hey, how’d you like a job as my bodyguard or a chauffeur?” So I says, “You’re trying to buy me off, man. You’re trying to co-opt me and it’s not going to work.” And I started hanging around the studio with him and we had a great time. He writes about it in Chronicles, you know—allegorically.

You know, we always moved in the same circles, druggie-type circles in the West Village. The guy who lived next door to me in the West Village was the guy who Dylan originally crashed with, Ray Gooch. So, there was a connection right there. There were generally fewer people around back then.

Then Dylan wrote “Dear Landlord,” which was the first song about the Dylan- Weberman relationship, and it’s full of threats.

He was right to see you as threatening, no?

No. He was threatening my life and stuff. He could get into a really creepy fucking head, where we’ll be sitting around and he wouldn’t turn the lights on in Houston Street, and he’d be looking at that church on Houston and Sullivan—St. Anthony’s—and it would all get real gray and everything. And then he’d say, “Al, if you get into my life, I might gain a soul.”

I says, “Gain a soul? What do you mean, man? Are you threatening to kill me, are you gonna kill me?” He says, “No, but I know some mafia people who might.”

But guess what. He didn’t want to be blackmailed by the mob for the rest of his life. You know so he went around, he did a number on me himself. He caught me on Bleecker Street and beat the shit out of me.

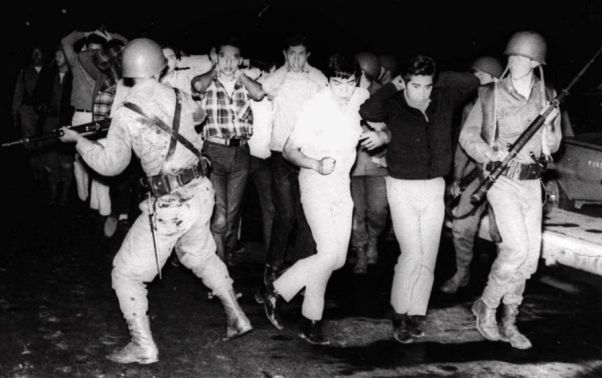

(Photo courtesy of A.J. Weberman)

You were like something he couldn’t get off his shoe.

I was threatening his whole thing. He couldn’t shoot junk in peace. And then I chased him out of Greenwich Village by having a birthday party in front of his house and it was in the centerfold of the Daily News. After that, he couldn’t live in that neighborhood anymore. There were too many hippies camping out in front of his house and stuff.

You could have just left the man in peace. Why did you bother him?

I thought he was a sellout. You know, he sold out the left. But guess what, Dylan was never a leftist. He just fell into the easiest thing that would make him famous.

It was a big fuckin’ laugh what Dylan did. He had people singing how many years can the cannonballs fly before they’re forever banned? And if you look at Dylan in other contexts, he says “catch a cannonball bring me down the line, my bag is sinking low and I do believe it’s time.” So he’s saying, “Let’s find a black heroin connection, my bag is sinking low”—i.e., I’m running out of dope. “How many times must the cannonballs fly”—cannonballs are out of control, namely black people, “before they’re forever banned.” And what he means by banned is, people were banned in South Africa who were part of the ANC, because they opposed Apartheid.

That’s nuts.

Dylan sings racist sub-content, pro-apartheid sub-content, in his lyrics.

You understand that this is your own, very personal interpretation of Dylan’s lyrics, right?

Time after time these things come up. You used to ride on the chrome horse with your diplomat, you used to have diplomatic relations with the biggest exporter of chrome, South Africa. Who carried on his shoulder—Who shouldered the white man’s burden—a siamese cat, slang for a black man, a nigger. Ain’t it hard when you discovered that he really wasn’t where it’s at—wasn’t it hard for you to rationalize what you’d done when you decided to break diplomatic relations with South Africa.

So, that’s where Dylan’s head is at, man. He’s a fucking racist, he’s a fucking Holocaust revisionist, and he’s a Nazi fucking sympathizer. But when I knew him he was a proud Jew, OK? And I was a self-hating fucking Jew, pro-Palestinian, digging my own grave. And not just because I was Jewish. I was a hippie, too.

But then in the eighties, when Dylan wrote “Neighborhood Bully” about the scapegoating of Israel, did you feel some sense that maybe the two of you were on the same trajectory, after all?

Oh, it was a great song, you know. But then Dylan became a Christian. So, he sang, your father was an outlaw and a wanderer by trade, he taught me how to pick and choose and how to throw a blade. OK, so your father is an outlaw—your antecedents killed Christ—and a wanderer by trade, and they were forced to wander the world because of that. He taught you how to pick and choose—the chosen people—and how to throw the blade, circumcision. He oversees his kingdom so no stranger does intrude—he watches very carefully who he takes in and allows to convert to Judaism.

I also discovered backwards masking. You know, when I played “If Dogs Weren’t Free” backwards, it said “If Mars Invades Us” or something. I was friends with Jann Wenner, and so Jann ran it on Random Notes in Rolling Stone. Then people began to play records backwards and they got “Paul Is Dead.”

When you look at Jann Wenner now, he’s buff, right?

I don’t know how he did it, he must be taking steroids or something. When I knew him he was a little wimp I could push around. You know, I got him in the Eastside Bookstore once and threw him up against the wall. But now, I don’t know.

Do you believe that decoding Dylan lyrics for the past 50 years has really been the best use of your highly original mind?

It was like, you know, when you’d buy Ovaltine and if you get enough wrappers they would give you the Ovaltine secret decoder ring, where each number on the ring represented a letter. So, you’d tune into the Ovaltine hour and then you’d copy a letter and then another letter and then what was the message? Drink Ovaltine.

This is another case of that. I wasted my fucking life trying to fucking understand this stuff.

So, you went from Dylanology to Meir Kahane and his followers or proteges in the JDO, the Jewish Defense Organization.

It was Mordechai Levy who came by to spy on the Yippies for the secret service, essentially. Levy came across to spy on me and he didn’t find much anti-Israel stuff among the Yippies. It was all basically, you know, pro-pot single-issue politics. And then he started doing data mining on Nazis. You know, he would find a Nazi’s phone number, call up the business office and say “Could you read me back the numbers that were called from this number.” And then from those records he’d do another search on everyone that the Nazis called. And in that sense he sort of unraveled the neo-Nazi network in the United States at the time.

I was very impressed by his methodology. And essentially he rolled me over. He let me hear calls with Palestinians where he would get them to admit they were working with the Klan. Then he started the Jewish Defense Organization, and then any alleged acts of, shall we say, vandalism, ceased after we formed the JDO, because you can’t do both things at once.

What is the point of what you do now?

The purpose is to fight the Nazis essentially. I’m not like an armchair anarchist or revolutionary. You know, when we were fighting against the war in Vietnam, we were instigating riots.

Well, it would hard to get the Jews of America to riot about anything these days. You could give Iran, say, a nuclear bomb in broad daylight, and you would barely hear a peep from these folks. You could round up all the Gypsies, or the Guatemalans, and put them into concentration camps. Regardless of their political orientation, Jews in America are some pretty wealthy, self-satisfied white people these days, and they are largely ignorant of their own history. That’s why I like hearing stories from people like you.

You’re just mad at Bob Dylan, because you wanted to have a relationship with him that he clearly didn’t want to have, because he thought you were a nut.

No, I’m not. I’m telling you the truth, so you know.

Back in the days of the JDO, a lot of Jews were being put into schools that were integrated for the first time. And then you had the whole Bed-Stuy-Brownsville, community control of the school of school boards, where they threw out the Jewish teachers. So, a lot of Jewish kids were radicalized.

What turned me off to the JDL was the “nigger, nigger, nigger” all the time, you know. The Yippies were opposed to the JDL. We published their credit card numbers in the Yipster Times, and then they came around with baseball bats to beat my head in. I said, “Hey, you’re getting all these charges on your bill, you know what you can do you can get the legitimate charges taken off too you know while you’re at it.”

Kahane was an interesting guy, got kosher food in the prisons. Common fare. That benefited the Muslims, too.

What do you think of Kahane now?

He was a theocrat. He wanted religious police. He was a racist. Israelis decided he was a racist. Ultimately it’s their call.

The Soviet Jewry issue was one place that he had a positive impact. His violence was appropriate there. It threw a scare into people, especially the brain-dead Jews who ran the national Jewish organizations in America, both then and now. It also scared the Russians.

Yeah, absolutely. He put a lot of heat on the Russians. There’s no doubt about it. He went to prison for it, too.

And what do you think about the fact that Kahane worked for the FBI all those years?

He hated the left essentially. But I would have to file an FOIA request and see if I can get his reports to the Feds or his contact sheets or whatever.

Kahane gets out of school and becomes an undercover informant for the FBI infiltrating Klan activity, so he almost looks like a civil rights guy. Then he moves to the Russians and the Soviet Jewry thing, and then he is revealed as an extreme theocrat and a racist. What I’ve always wondered is, did he continue working for the FBI the whole time?

No. Once he started with the so-called terrorists, they don’t want to touch him. You know he’s committing, he’s inciting the commission of illegal acts, he’s participating to some degree. You know they dropped him after that.

Then, of course, in an irony of history, Kahane is the one that al-Qaida ends up targeting first, because they recognized him. They’re like, “That guy’s is really dangerous, because he’s the Jewish version of us.” And the failure to really follow up on the investigative leads in the Kahane assassination—because everyone thought that Kahane was simply a crazy Jewish racist who embarrassed everyone and probably did deserve to get shot—opened the door to the first World Trade Center attack, and then to the success of the Sept. 11 plot.

It was stupid. They had Emad Salem in there for the first World Trade Center bombing, this guy Carson Dunbar took him out, he was head of the New York FBI office. Then the bombing occurred, they put him back in the cell, and then they arrested everyone including Sheikh Rahman, and they made tapes of Sheikh Rahman talking to Emad Salem. And Emad Salem is saying, “Let’s bomb the FBI building.” And Rahman says, “Slow down slow down. It took us three years to train the one who killed Kennedy.” You know, and when this came up on trial, everybody the U.S. attorney, Lynn Stewart, the whole fucking crew, they weren’t going to say, “Hey, that could have been Robert Kennedy.” They all just laughed and said, “Oh, how could it be John Kennedy?”

And guess what: Rahman was close to Mohammad [M.T.] Mehdi, and Mehdi was close to Sirhan Sirhan, who did kill Robert Kennedy.

When you read accounts of the assassination of Robert Kennedy, it’s always presented as some inexplicable Oswald-like lone gunman event—except the man who did it, Sirhan Sirhan, had a very clear political purpose, which was to mark the anniversary of the Six Day War and to protest American support for Israel. He killed Robert Kennedy because he understood him to be a powerful American Zionist who was running for President.

Robert Kennedy was going to send U.S. fighter jets to Israel. Sirhan Sirhan was a Palestinian, and he was trained by a Muslim Brotherhood cell. The FBI still won’t give me documents about this one suspicious guy who ran a little study group in which Sirhan Sirhan participated, an Egyptian. They won’t give me his name.

Let’s talk about your relationship with John Lennon.

How that started was that we invaded Allen Klein’s office, he did the fucking Concert for Bangladesh album, and he kept all the money instead of giving it to the Muzzies in Bangladesh. So, New York magazine does a whole story on it, and we figure, “Hey, if this guy has to rip off the starving people of Bangladesh, he must be one hungry motherfucker.” So, we had our free lunch for starving music executives program where we went to the dumpsters on 1st Avenue near the fruit stands, got all this rotten fruit, came into Klein’s office, and tossed it around. Fucking Phil Spector was there man, he attacked my old lady, Anne. So, then he had the bodyguards throw us out.

So then, John and Yoko call me. And Yoko says, “Come on over for tea with you and Anne.” You know, so we went over to Bank Street. And then the friendship started.

What do you think they wanted? Did they want protection, because they were new to New York?

No, no. They were pissed off at Allen Klein, they liked what we did, you know. We spoke for them, too. They liked activism.

That guy John Lennon was a revolutionary. You know, “working-class hero.” He was into that fucking IRA. I met IRA guys over there who were selling hash and smurfing arms and sending it back to the IRA in Ireland. He was crazy, you know. He gave me money to start riots in Miami, at the Republican Convention.

So, Lennon believed in his politics, unlike Dylan?

You know, Lennon, he was using smack a lot of the time. You’d go there and they’d say, “Oh he’s depressed, you can’t go in the room.” They’d just load me up with records and Yoko’s art and everything, you know. And, in retrospect, you know, I would say he was going through cold turkey. He had no track marks, he was snorting at the time.

Back when Lennon convinced me he was up to revolutionary shit, we went and we put a phone line, we went to the back of the house, to John Cage’s phone line, and put an extension into Lennon’s house so when Cage went to sleep at night, Lennon could make his calls on Cage’s line without the FBI tapping them.

Did John Cage ever know that?

I don’t think so. I know Andy Warhol knew that we stole his furniture. What happened was, we’d just moved, we got back from Miami and we had the Yippie headquarters on 3rd Street and 2nd Avenue in a basement on the Angels block. So, we were looking for like a space heater or something. So, I was walking by Cooper Square and I saw this door was busted open. So, I walked upstairs and then holy shit, there was all this art deco stuff was there. You know bureaus and lamps and clocks made out of marble. I said, “Wow, somebody abandoned this.”

So, I had this guy come with a truck and loaded it all into a truck and brought it back to my loft and to the Yippie house. A week later, I read in New York magazine that somebody looted Andy Warhol’s art deco stash. So, later at a party, Dana Beal went over and told him, “Andy, we were the ones that took it, we thought it was abandoned property.” Andy says, “I don’t care, as long as you didn’t sell it, it’s OK with me.”

What did Lennon want from America?

What did he want? He loved New York, you know. He liked Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman. You know, they’re entertaining people. And David Peel, of course. He was a revolutionary, so he just fit right into the crew basically. He came to demonstrations.

I had one, you know, “Paul Is Dead,” we were demonstrating outside Linda Eastman’s parents’ house. You know we had a hearse and we had a big mock funeral for Paul McCartney because his album was so apolitical. So, he and Yoko, they showed up in bags and read a whole statement.

When did you stop seeing him?

After he moved to the Dakota. Then they got real heavy into heroin. Really heavy, you know. They became addicts.

Did you ever see John Lennon use heroin?

No, he knew I was opposed to it. Because I was saying that Dylan was an addict, and he had sold out his left-wing thinking to use heroin—when of course there was no left-wing thinking. He just became the Marxist minstrel, because that’s what was happening at the time.

You’re just mad at Bob Dylan, because you wanted to have a relationship with him that he clearly didn’t want to have, because he thought you were a nut.

No, I’m not. I’m telling you the truth, so you know.

But you admire Dylan. You think he is very smart.

Oh yeah, he’s smart. He’s a freak. He played at Hubert’s Flea Circus. You know, you could ask him to sing any song and he’d sing it, like some kind of machine on 42nd Street. I’m waiting for him to write about that, because I used to go to Hubert’s all the time. He loved it in New York at the time, the gaslight. The Café Wha? I worked at the Wha? I paid Jimmy Hendrix $30 a night for three sets.

Jimi Hendrix is the one person in music history that I would trade everything I own for the chance to spend three hours in a small room where he was playing live.

(Photo courtesy of A.J. Weberman)

Oh, I heard him all the time. We would drop the actual glassware on the floor when he started to play, and then sweep it up later on, you know, so we wouldn’t miss a second. We’d go out and listen to him. Man, he’d go crazy, he’d play with his tongue, he’d play behind his back, he had all kinds of stuff—a lot of Dylan covers, “All Along the Watchtower,” “Like a Rolling Stone,” “Wild Thing.”

I remember Jimi saying to me when Eric Burdon was in the audience one night—“He’s going to sign me to go to England, I’m going to have plenty of money man, and I’m going to take every drug there is.” And I says, “You sure you want to take every one?” He says, “Yeah, I’m sure.”

He was a nice guy. Friendly, not condescending. He saw himself as basically a black Yippie. He gave the money to Abbie Hoffman to send joints to Congress. Every congressman got a joint. And, according to Abbie, a big percentage of them didn’t turn their joints over to the FBI.

Did you believe that pot was going to change people’s heads and change American society for the better?

And acid. We were going to squirt the cops with DMSO and LSD in water guns. DMSO would make their skin a permeable membrane. And of course the LSD would be psychotomimetic, it would make them crazy. But people don’t take acid anymore.

I don’t even know where I’d get acid in New York City these days. And if I did drop acid in my present condition, I would probably flip out and become a real-estate broker at Corcoran or something. So that part of my life is clearly over with.

It became an ordeal. But it could end regressive behaviors it can end alcoholism, it has good therapeutic value if taken under the right circumstances.

What do you make of the speed at which pot is being legalized in America?

I’m happy about it. You know, I got radicalized when I sold five joints to a fuckin’ undercover cop at Michigan State. I was facing 20 years on the sail, minimum mandatory, 10 years, when they vacuumed my pockets and found little minute amounts of cannabis. I had to come to New York City, get a job from the Lawrence employment agency, go see a shrink, you know, and then pay the district attorney 5,000 to let me off the fucking hook.

I turned Dana Beal on to pot, and then Dana came to New York City, escaped from a mental hospital where his mother put him for attacking someone in his class, he got a job at Klein’s on Union Square, in the record department, and then he moved on to the Record Hunter on 5th Avenue and 42nd, enrolled at NYU, was an A student. And then I turned him on to LSD. And he said, I want to be a revolutionary. So we had the first smoke-in in Tompkins Square Park, in 1967 in the Summer of Love. The East Village Other gave us an office on Avenue A and 10th Street, and we put a big sign in the window, Psychedelic Revolution. And anyone, we had marches. Anyone, anytime there was a pot bust we’d march through the East Village, and people were very happy to have us doing that. They’d throw flowers at us. Including the fucking flower pot.

So, then we opened three stores, Dana got busted, he had to go underground, and he hooked up with the Weather Underground in Wisconsin, and we continued to push for legalized marijuana. Myself, publisher Rex Weiner, and some other people, we had the first Marijuana Day Parade. May Day is J Day. John and Yoko sponsored it one year. We had a giant joint on stage. Yossarian, the underground cartoonist, would do the posters. We had had somebody smoking pot in an iron lung, had a hippie tied a little kid in a wheelchair or a high chair and a hippie forcing him to smoke pot, you know all kinds of weird, bizarre stuff. And then NORML came along, and so it became more widespread.

The current President of the United States writes in his memoirs about smoking pot.

Yeah, he lived next door here, in the adjoining building. You can see from the terrace downstairs, that fire escape where Obama said he went out to smoke dope. I think it’s a progressive thing. But then you know you’ve got Nazis like Ron Paul who want to make all drugs legal for people who are looking for a shortcut to happiness, who are never going to be able to find that happiness via traditional economic means. That’s part of his hidden agenda to fuck up the African American community, because he is basically a Nazi at heart.

I was staying at Grover Norquist’s town house, right—

Grover Norquist, the Republican direct-mail guru?

He was like a libertarian, he loved rock and roll, he had the greatest collection of rock records, man.

You were friends with Grover Norquist because of his record collection?

We had a friend in common, and I needed a place to stay in D.C. So, my friend takes me over to Spotlight, which was a real right-wing John Birch-type magazine, right, because I’ve done research for [late Congressman Henry] Gonzalez and [Sen. Richard] Schweiker, who created a Congressional Commission to investigate the conclusions of the Warren Commission about the circumstances around Kennedy’s death. And so I show them the tramp shots.

And so they say, “Oh this is very interesting. What’s your name?” And I say, “Allen Jules Weberman.” And then the guy says “Allen Jew Weberman?” And so I say, “Who are these fucking guys?” So, then I went back and listened to their stinking broadcast and I says, “Holy shit, it’s fucking Father Coughlin has come to life again.” And then I started to subscribe to the Spotlight. And in every issue, it was Ron Paul this, and Ron Paul that. Ron Paul was at this meeting. Ron Paul was their hero. That was his fan club, his base.

To have somebody like Ron Paul alive is like having a cancer. His big catch-phrase is “the New World Order.” Do you know what the new world order is? The new world order is where the Jews control everything. It’s another way of saying ZOG, the Zionist Occupation Government. It’s dog-whistle politics.

Do you feel the same way about Ron’s kid, Rand Paul?

Yeah. He wants to cut off aid to Israel. And he goes to Israel and says how much he likes the place and then ultimately he wants to destroy it. You know what he was named after? The Rand, the South African currency.

That’s hilarious. But is that true?

That’s what I believe. Ask Ron Paul.

What do you think of this city now? I was born here, I grew up here, but I stay out of Manhattan these days, because it generally depresses me.

Well, it’s lost a lot of its interesting places, really, like 4th Avenue and the bookstores, the electronic places on Courtland Street. You know it’s become pretty homogenous—Payless Shoes, Starbucks, ATMs, Duane Reade. And basically you have de facto segregation now, in that you need to have an income that’s like 40 times the amount of the rent per year or something.

Right. No one is a racist anymore, because even that would mean that they had an allegiance to something other than money. But then I remember the shooting galleries and the junkies, the people living in abandoned buildings, and that time wasn’t so good, either. I hate that fake nostalgia for the New York I grew up in from people who came here in 2011 to be stockbrokers or work for some crappy Internet company. The old New York City had its virtues, but it was pretty dangerous and shitty.

Everybody was getting ripped off. You know you work at a job, make $50 a week and you buy something and then next thing you know the junkies have come and stolen it from you. My customers at low numbers in the East 60s were getting home and people were trying to break down their doors in home invasions.

The city was fucking chaos, you know. But for me, it was wonderful. Because they were taking riff-raff. Everybody wanted to rent to me, even on MacDougal Alley, a little town house they were going to rent opposite Washington Square. I finally settled on 240 Central Park South, overlooking the park there. Antoine Saint Exupery’s old apartment. It was a love nest for somebody who owned 6th Avenue Electronics. So I had a terrace, wood-burning fireplace, in a tower of 240 Central Park South. And it was rent stabilized. I had to pay money to get the guy out and pay a fee to the broker, but they didn’t really scrutinize your records so much, because it was a buyer’s market.

But the city was deteriorating. There were pornography places on every block. There were all kinds of roving gangs around 8th Avenue and 42nd Street and 9th Avenue.

Was it fun being a drug dealer in the city?

Yeah, except for the rips.

Did you have guys with guns take stuff from you?

No, just once. What happened was this idiot guy from High Times was doing some story on coke dealers. So he calls me up and he says, “Oh do you want me to bring my friend around, he’s a big coke smuggler.” I says, “No, don’t bring him around.” So, he brought him around anyway. Then the guy sent his crew back to rip me off. You know so when somebody left, they came up, they cuffed me up, you know hit me a couple of times with a gun, kicked the dog, and stole a bunch of reefer from Gainesville, but they missed the mushrooms, you know. So, I says, “Aw fuck.”

So, what I did was I put double doors on there so you got buzzed in one door, and you’re in a little hallway and then you get buzzed in the other door with a TV camera to see who it was and then tear gas that could be remotely controlled. I hired somebody to put the doors in.

And sure enough the rips came back. And what they did was there was next door we had Studio 10 at 10 Bleecker Street, Quiet Riot played there and other bands of note. So I look out the window and all of the sudden, the black guards are white. The rips had kidnapped the guards, they’d kidnapped the black guards and tied ’em up and put ’em inside 10 Bleecker, and got their uniforms and were outside the door. So then this woman comes who was not a criminal herself, but comes from a crime family whose name would be easily recognizable, and she refused to open the door.

So they let her go, and then I buzzed the guy in. You know, so he comes in and then all of a sudden, the lights go out, the tear gas goes off, and then me and this guy who later actually ended up working in Times Square as a bouncer in one of the peep shows, cleaning up the semen with a fucking mop, and this other guy Smitty, who was also happened to have organized crime connections, but was forced into it by his father. And they come down and we have two fuckin shotguns, Ithacas—we cocked the fuckin Ithacas and said “We’re gonna fuckin blow you away.” And then boom, we hear a fuckin shot goes off. I release the front door and he goes limping away. He shot himself in the leg!

So that was the Wild West back then, man. The cops saw everybody going in and out in and out, all these people like Jim Jarmusch, I ran into him the other day, he was a customer. Ginsburg brought a whole bunch of people around. The President’s brother [name has been excised at lawyer’s request]. Other people I don’t want to mention. That photographer dude who did the pictures of the young kids, Robert Mapplethorpe, brought his crew around. The people from Saturday Night Live, the writers, it was a salon. You know, everybody you could get jobs, you could meet, advance your career, meet other people. And then the cops chased us out and I had to start a delivery service.

And now you comment on stories on the Internet. What’s the pleasure in that?

Well, a lot of my comments are pretty absurd. Like this woman today, she ran, she came in number 75 in the marathon. So she said, “Oh I finished in 5 and 40.” So I says, “How can you finish in 5 minutes and 40 seconds?”

What are your favorite sites to comment on?

Well, I’m barred from Huffington Post, and I’m barred from the Gothamist. Wenner got me barred. You know because when they came out with the Rolling Stone thing, with the Chechen bomber’s picture on the cover of Rolling Stone, you know, then I said “Aw, man, Wenner is doing intellectual limbo. He’s reached a new fuckin low.” You know, I knew the guy was a fucking low-life from years back. But I didn’t realize it went this deep. Even his own writer Matt Taibbi wouldn’t defend him, put his heart in the defense, because he was almost killed by Chechnyan separatists in Moscow. And the Daily News, somehow I got banned from there.

The Forward, I was banned for a little while because I said that a lot of gay Jews don’t like Israel, because they were maltreated when they were younger by other Jews.

Do you think the open information culture that the Internet has created has been a good thing for American democracy?

It spread a lot of ignorance. It gives a lot of ignorant people a chance to express themselves. When you see some kind of a factoid, a lot of times it’s repeated time after time, so you just put it in quote marks and put it in the Google search, and then you can see that it comes up in certain groups over and over again. So you know that somebody’s started it and the rest of the idiots just promulgated it. But the big thing is that Facebook has changed a lot of people’s lives.

You like Facebook?

Facebook is good. It gives people a chance to express themselves.

There was something in your spirit, in good ways and bad, that is now widely diffused throughout the culture because of the Internet. It’s become part of our cultural DNA. You had so much passion and aggression and interest and you had tools and you were an obsessive. I think that energy is part of what makes the Internet run. That, and porn.

Right, right. Well, you know we were tied in with Cap’n Crunch, you know he lived at 9 Bleecker, and he was making the—

Yeah, the long-distance phone hacks. Ron Rosenbaum wrote a great magazine article about that, in the days when there were great magazine articles.

In Esquire.

[Stops to take a phone call]

They’re putting up like a garbage transfer point here, so all the wealthy people at Asphalt Green are pissed off. But guess what? Asphalt Green used to be an asphalt plant that the mob used to make inferior cement and stuff. So what are they so afraid of? It’s not going to be toxic, it’s just going to be people’s garbage. Rich people’s garbage!

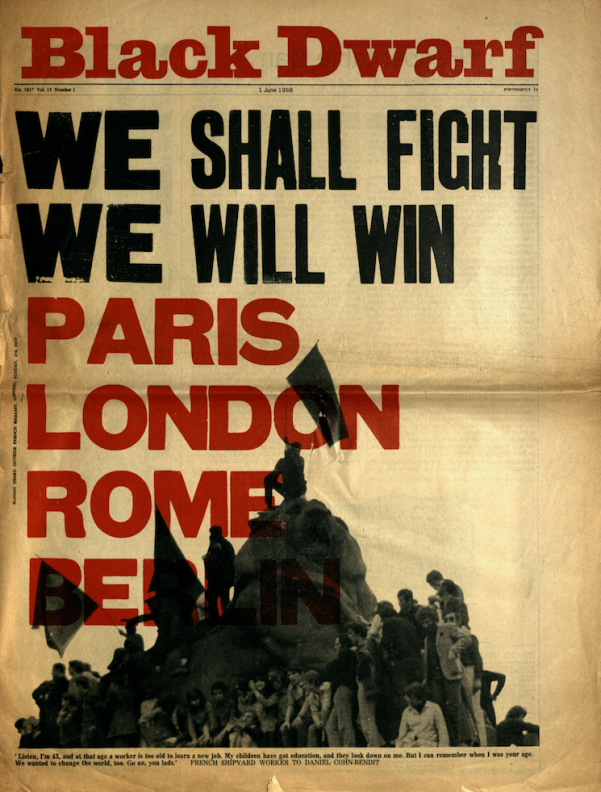

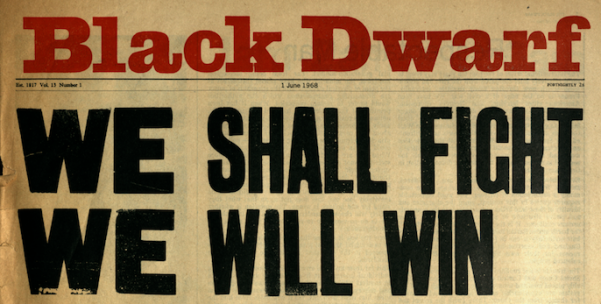

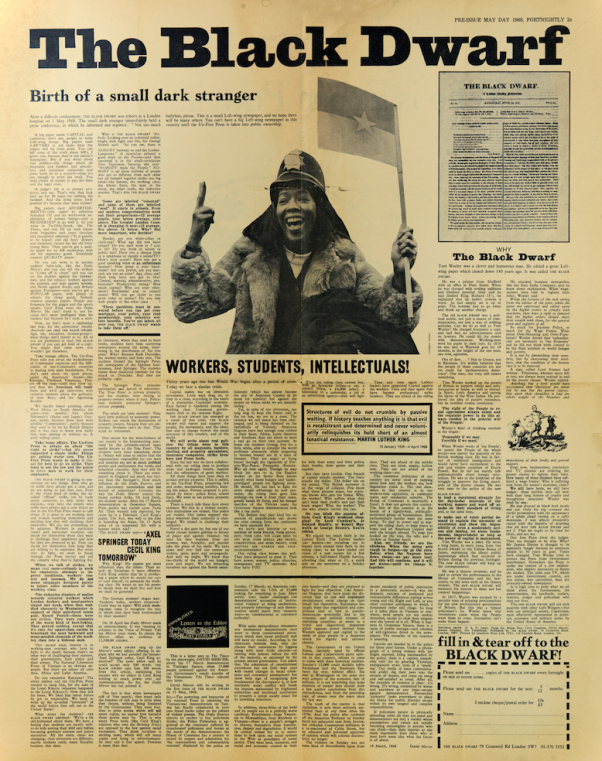

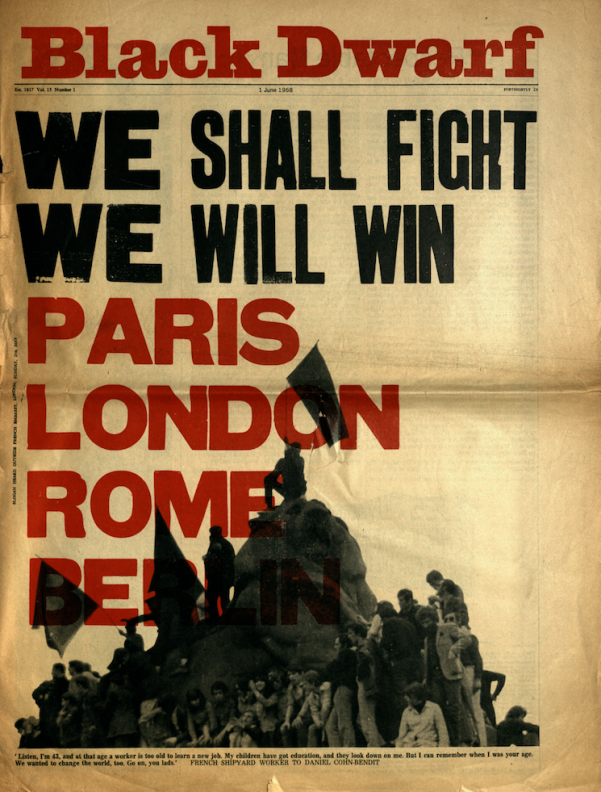

Andy Merrifield discusses the influence of Guy Debord and the Situationist International on the events of May ’68.

Andy Merrifield discusses the influence of Guy Debord and the Situationist International on the events of May ’68.