We Shall Fight, We Will Win: On The Black Dwarf and 1968

The Black Dwarf was announced with a free broadsheet on 1 May 1968 and published four weeks later. The inspiration was the struggle of the Vietnamese liberation movement against American imperialism that had taken over territories from the European colonial powers. The Tet offensive by the Vietnamese NLF (National Liberation Front) that year had witnessed an assault on most of the provincial capitals in occupied South Vietnam which culminated with a surprise assault on the US Embassy in Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh city), where the stars and stripes were lowered and the NLF flag hoisted. This symbolism, as well as real gains on the ground, marked the beginning of the end of the US war. The game was up. The tortures, use of chemical weapons, destruction of the ecology by defoliants carried on for another seven years. Imperial narcissism knows no boundaries. It was the Tet offensive that boosted the anti-war movements in the United States and across the world.

In Britain the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign grew rapidly. In October 1967, 10,000 marchers came close to entering the US embassy. In March 1968 contingents from the German SDS and the French JCR joined us as 30,000 people mobilised by the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign surrounded the US Embassy in London. We had been baton-charged by mounted police (‘The Cossacks, the Cossacks’ was our cry as we edged forward thinking of Vietnam and Petrograd 1917). Mick Jagger, marching with us, angered by police brutalities, thought we should have answered force with force. Britain was hopeless. A few months later he wrote Streetfighting Man. Culture was intervening in politics.

‘Hey! think the time is right for a palace revolution, but where I live the game to play is compromise solution

Hey, said my name is called Disturbance; I’ll shout and scream, I’ll kill the King, I’ll rail at all his servants’

The BBC refused to play it. He scribbled a note ‘For you!’ and sent it to me with the song. We published the lyrics in The Black Dwarf, aligned with a text by Engels on street fighting. A debate on the new music and the new mood erupted briefly in the New Left Review with Richard Merton (Perry Anderson’s nom-de-plume) arguing that:

“… it is incorrect to say that the Stones are ‘not major innovators’. Perhaps a polarization Stones-Beatles such as Adorno constructed between Schoenberg and Stravinsky (evoked by Beckett) might actually be a fruitful exercise. Suffice it to say here that, for all their intelligence and refinement, the Beatles have never strayed much beyond the strict limits of romantic convention: central moments of their oeuvre are nostalgia and whimsy, both eminently consecrated traditions of middle-class England…By contrast, the Stones have refused the given orthodoxy of pop music; their work is a dark and veridical negation of it. It is an astonishing fact that there is virtually not one Jagger-Richards composition which is conventionally about a ‘happy’ or ‘unhappy’ personal relationship. Love, jealousy and lament—the substance of 85 per cent of traditional pop music—are missing. Sexual exploitation, mental disintegration and physical immersion are their substitutes.”

In Britain music, in France cinema, were the auguries of what was about to come.

VSC broke with the more traditional opposition to the war. It declared its solidarity with NLF and supported its victory. Whereas the old New Left had launched CND and developed a ‘third camp’ position, the VSC responded to the conjuncture. The NLF was created, led by the Vietnamese Communist Party. It was armed by the Soviet Union and China. At one point, Bertrand Russell, distinguished VSC sponsor, wrote an open letter to Leonid Brezhnev, then leader of the Soviet Union, demanding that the Soviet Air Force be dispatched to defend the Vietnamese.

This was the political context in which The Black Dwarf was launched. It was conceived as a political-cultural weekly. The idea came from Clive Goodwin, a radical literary agent who became the publisher. The first meeting to discuss the paper took place at his house on 79 Cromwell Road. The room was lit by Pauline Boty’s paintings. She had been married to Clive and died of leukaemia in 1963. Present were Clive, the poets Christopher Logue and Adrian Mitchell, the playwright David Mercer, Margaret Mattheson, BBC script editor Roger Smith, D.A.N. Jones (who we wanted to be editor) and myself. Behind the scenes were Kenneth Tynan (who offered to review the House of Commons, but didn’t), Ken Trodd and Tony Garnett. We all agreed it was a great idea. Christopher Logue was sent off to look at old radical journals in the British Museum. The following week he returned with the name: The Black Dwarf. It was a polemical paper edited by Thomas Wooler in 1817 and agitating viciously and satirically for electoral and parliamentary reform. The title was inspired by the stunted bodies and soot-stained faces of coal miners.

Communication was slow in those days and it wasn’t till late afternoon on 9 May 1968 that we got news that something serious might erupt in Paris. The Sorbonne had been occupied! Five thousand people were packing the amphitheatre. Action Committees of various sorts were sprouting like magic mushrooms. The isolation of the Nanterre March 22 Committee had been broken. Of its two principal inspirers, Daniel Bensaid died some years ago, steadfast as ever, while the other Daniel (I think his last name was Cohn-Bendit) died politically. His corpse, I’m reliably informed, is currently on guard duty at the Elysee cemetery. He now regards Macron as the true representative of ’68. We published Sartre’s remarks to the Sorbonne students in the amphitheatre:

“Something has emerged from you which surprised, which astonishes and which denies everything which has made our society what it is today. That is what I would call the extension of the field of possibility. Do not give up.”

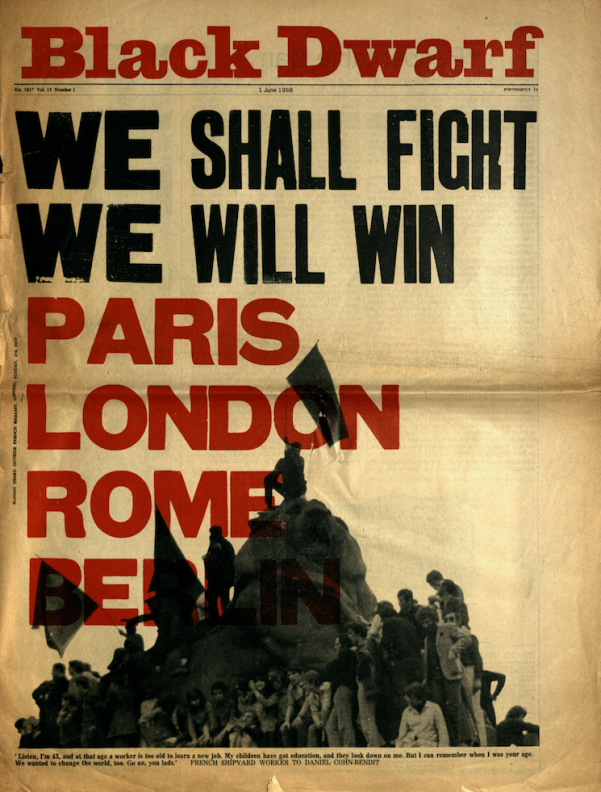

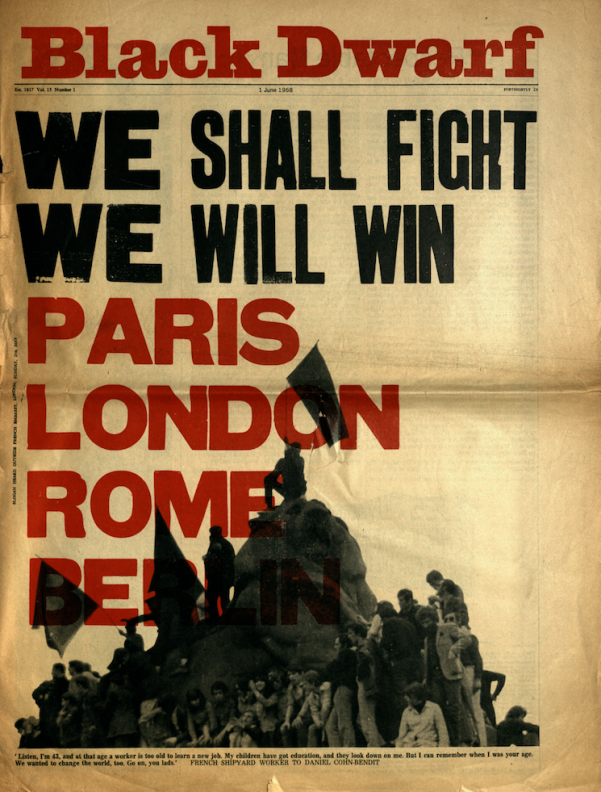

The night of the barricades on 10 May set France on fire. Soon the whole country was involved and 10 million workers went on strike, occupying factories in Rouen, Nantes, Paris, Lyon, etc. It seemed as if the Paris Commune had been reborn. As the first issue was brought to us, I thought the cover chosen by D.A.N. Jones was too weak and watery. We needed to identify with the movement. On a scrappy piece of paper, I wrote: ‘We Shall Fight, We Will Win, Paris, London, Rome, Berlin’ and handed it to our designer, Robin Fior. Everyone except Jones agreed. We decided to pulp 20,000 copies of the first issue. Jones walked out and I was appointed editor.

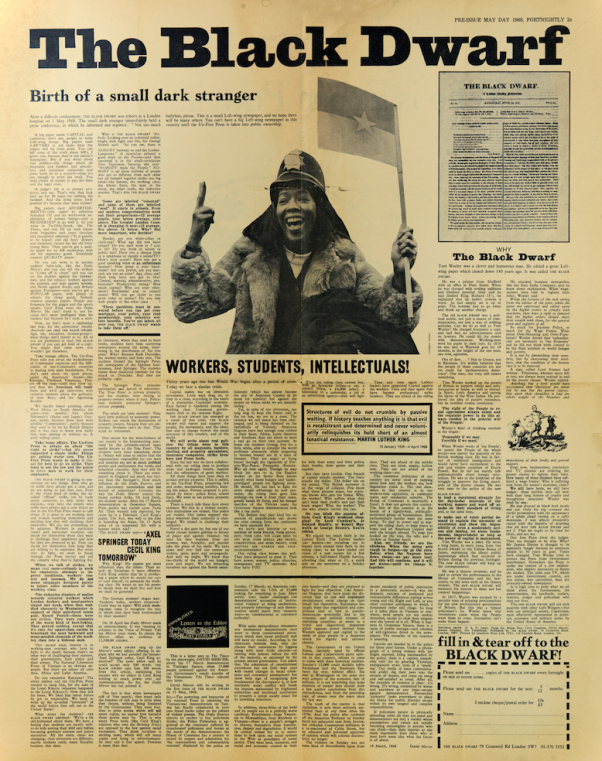

In our May Day broadsheet in 1968 we had described the first Editor of the old paper thus:

“Tom Wooler was a clever and humorous man. He edited a great left-wing paper which closed down 140 years ago…He was a printer from Sheffield with an office in Fleet Street. When he was charged with writing seditious and libellous material (they said he had libelled King Richard II) he explained that he hadn’t written a word. He had simply set it up in print!”

He was acquitted but forced a change in the law. Henceforth printers became liable as well. Ironically our Black Dwarf was rejected by almost a hundred printers and we finally ended up taking the train to a printer in Bala, North Wales the only printshop prepared to do the job. It was the same with distributors. They rejected us en masse. Only the great Collets’ bookshop on Charing Cross Road in London and a few radical bookstores elsewhere in the country (all gone now) stocked the magazine. We were dependent on street sellers and Mick Shrapnell a VSC/hippy militant used to sell 500 copies on his own. The musical Hair , a huge West End hit, helped with the lead actress displaying the latest issue on stage in every performance. Our supporters in the painting fraternity: David Hockney, Ron Kitaj, Jim Dine, Felix Topolski didn’t have much dosh but donated paintings that we auctioned. Other donors would drop in with much needed cash. We managed to print 45 issues of the paper and were amongst the first to declare 1969 as the ‘Year of the Militant Woman?’ with Sheila Rowbotham’s stunning manifesto. I had told the designer David Wills that it should be designed like an old-fashioned manifesto. The unreconstructed pig tried to subvert the message by placing the manifesto on two gigantic breasts. Sheila rang in a state as she saw the proofs. I rushed over, had it changed and sacked Wills on the spot afterwards. These things happened.

Politics was getting polarised and a number of the staff and EB members split on my decision to publish three pages from dissident ANC guerrillas who had been tortured and denounced by their leaders simply for asking critical questions of overall strategy and tactics. I was convinced they were genuine. Supporters of the ANC leadership were horrified when the magazine appeared. Thabo Mbeki led a squad of supporters to buy up all our copies in Collets. We reprinted. But the vote had revealed a division between Trotskyists and the others and a split took place. Was it avoidable? Probably, but left politics was becoming more and more polarised after the French May and the Prague Spring. A group of us left and established The Red Mole, much more linked to the IMG [International Marxist Group]. Another problem was lack of funds. We were in trouble anyway but the split was regrettable. The non-Trotskyists set up Seven Days , a paper I liked very much which should have survived.

The Black Dwarf and Seven Days are now digitalised in full and made available by the Amiel-Melburn Trust archive, an extremely valuable resource.