“Drugs. Sex. Revolutionary violence. From its first pages, Susan Stern’s memoir With the Weathermen provides a candid, first-hand look at the radical politics and the social and cultura…

“Drugs. Sex. Revolutionary violence. From its first pages, Susan Stern’s memoir With the Weathermen provides a candid, first-hand look at the radical politics and the social and cultura…

Tag Archives: counterculture

Heaven and Hell Coffee Lounge in Soho, W1 |Eric Lindsay

This is a brilliant blog post about the Heaven and Hell Coffee Bar in Soho written by it’s founder Eric Lindsay (link at end). Sadly not with us anymore. Check it out!!

Ray Jackson and I opened Heaven and Hell in late 1955. I had the idea from when I had been working in Paris, where there was a type of cheap cabaret called “Ciel at l’Enfer” “Heaven and Hell” in Pigalle. The name and the place intrigued me, so later when I was in Paris again with Ray, I took him along to see the place and he also thought it was tacky but great.

The name stayed in my memory for a later date.

Here are some old photographs that I have just come across to show you how much the original impressed me. “Ciel et l’Enfer” was an intriguing name.

We had already sold the Regency Coffee Bar in East Sheen, which we opened with £200, £100 each, sometime in 1953. The Regency look was in, so we bought chairs from an antique shop in Putney for 5/- each and the owner of the shop taught me how to give them the antique look. We bought cheap floor covering, Ray’s uncle hung the wallpaper and my mother made the tablecloths and curtains. I used the same red Regency striped material to upholster the chairs, it was all a bit make do and mend, but the final result looked great. The major expense was the Gaggia Coffee Machine, which we paid off for. So espresso coffee came to East Sheen!

We thought we would do business, well forget it! I thought we would be stuck there for the rest of our lives. East Sheen was half way on the bus route between Hammersmith and Richmond, and really one should never get off the bus. I was convinced it was a place that people just stopped off to die. There was literally no business. Although everybody who lived there had the airs and graces of society toffs, they had no cash flow to buy a cup of coffee. In fact they hadn’t got a pot to piss in! But they lived in East Sheen so they had a little status. (They thought!)

Fortunately both Ray and I continued working in Theatre and TV, and Ray in films because we needed something extra to survive.

We were ‘so busy’ at the Regency that one person could run the whole place – serve coffee, do the cooking, the lot. So Ray and I worked alternate days. When I was on duty I would take an order and call out to the kitchen and then rush round talking to myself (the invisible chef). At least it was a good way to pass the time and it gave the customers the idea that we had staff. I thought I was going to be stuck there forever. We earned £10 a week each. My bus fares cost me £5, so you can see I was really in pocket! Finally we managed to sell the place to a guy who had retired from Claridges Hotel with a pension who wanted something easy to do in his retirement years. Well I could have told him that he wouldn’t be rushed off his feet here, but I didn’t and we sold the Regency for the princely sum of £1000, which was a profit, and we both breathed a sigh of relief!

We then started searching around for empty premises in Soho because I certainly wasn’t going out of town again. It had to be a shop and basement so that Heaven could be on the ground floor and Hell downstairs. We finally came across a little shop with a basement at 57 Old Compton Street. The ground floor had a small jewelry shop sharing the premises called of all things “Going Gay”. Do you think it was an omen? The gentleman who owned the freehold was called Harry Shanson, and he owned all the freeholds of 55, 57 and 59 Old Compton Street W.1.

Shaws the estate agents who were handling the property arranged for Ray and myself to see Mr. Shanson in his office in the City. Well, somehow it must have been our lucky day, because we talked to him and told him we were actors and what we wanted to do with the premises and the name we were going to call the coffee bar and the whole theme. He was interested in everything we had to say. Finally the question of rent came up and Ray and I nearly fell of the chairs when he told us what he wanted. It was far too much for us to afford. We got up to leave and explained that we just couldn’t afford to pay that sort of rent. He asked us how much we could afford. I told him half of what he was asking, to which he replied, “O.K.” With that, we both nearly passed out. Ray and I left his office floating on air.

We started work at 57 Old Compton Street. From the St. Martins School of Art we found a designer to make the plaster casts for the lights in Heaven and also Hell. Beforehand, Ray and I decided that Heaven should have an ethereal theme with sun flowers for lights with cherub faces. The staircase leading to Hell was a giant Devil’s mouth, which you walked down into. Hell was totally black with red flames climbing up the walls.

Out of the walls for lights we had these arms holding lighted Devil masks. The emergency exit, which we had to have, was a ladder in the middle of the room closed on 3 sides with a red curtain on which was a full length painting of the Devil with horns, tail and pitch fork. It was all very atmospheric and the customers adored it. On the street wall we had a light box with a colour transparency of Heaven and below it Hell. From the moment we opened, the place was full, at lunchtimes and evenings. I used to have to stand on the door letting customers in as a seat became vacant whilst they were queuing out in the street. Not many people wanted to stay in Heaven, they all wanted to go to Hell. No pun intended. As you may gather, business was fabulous, especially when the Soho Fair was on.

Over the years Harry Shanson and his wife became firm friends. He was one of the kindest people in the world. One day when we had been running quite a few years, Harry’s son, who was a bit of a monster when he was young, came in and said to me, “My daddy owns this place! It’s ours.” So I politely said to him “Fuck off!”

There was never a dull moment in Old Compton Street. The 2 I’s was next door. The customers would go from coffee bar to coffee bar. The 2 I’s used to have their windows smashed in regularly. We fortunately were left alone. Everyone seemed to making money and at 9 pence a coffee it was some hard going.

Prostitutes were on every street corner. The flat above Heaven and Hell was occupied by Suzy, an elegant French lady of the night who really would have been more at home in Mayfair, but I suppose she wanted a quick turn over! She wore the stair carpet out all the time. Next door at No. 57, Jackie, another French beauty, much younger than Suzy, could turn 100 customers a day. My mother, who used to come up to town regularly, used to sit in the window in Heaven and keep score. She was so intrigued by it all.

Well, the time came when Ray and I decided that we would like to get a flat together, so I spoke to Harry Shanson. The lovely Suzy got her marching orders and Ray and I moved into Flat 1, 57 Old Compton Street at a rent that he asked us what we would like to pay, so that also was very reasonable. It was a known fact that he could always get at least double from the tarts. I did think she might send the ‘heavies’ in after being thrown out and when she found out that we had taken the flat, but no, she was always pleased to see me and talk when I saw her on her new beat at the corner of Greek St. and Old Compton St. Working ‘flats’ were not that difficult for the ‘girls’ to come by.

Suzy had kept the place spotless, after all she had he own French maid who was on duty full time during the working hours. The bedroom looked as though it had seen plenty of action. But after we had redecorated the whole place even Suzy wouldn’t have recognized it as her own little bordello.

We never had live music in Heaven and Hell, just two jukeboxes one in Heaven and one in Hell, with the same records in each. It was easier than all the hassle with live music because the customers never left. With us, they stayed about an hour and left, rather than sitting there all night. Also it was much more profitable as we would get loads of double plays from the 2 machines.

So the money rolled in and we were ready to roll out onto our next venture which was:

“THE CASINO de PARIS STRIPTEASE THEATRE CLUB”

P.S. If any of you ‘older readers’ happen to come across a picture of yourselves taken inside “Heaven and Hell,” I would be very happy to include it into my blog.

Source: Heaven and Hell Coffee Lounge in Soho, W.I. | ericlindsay

Soho stories: celebrating six decades of sex, drugs and rock’n’roll

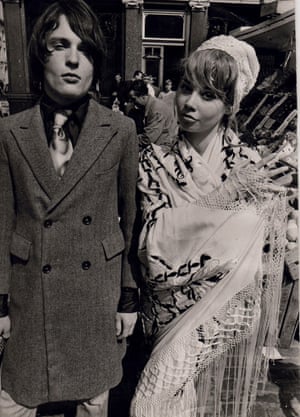

Soho’s fashionable Carnaby Street in the 1970s. Photograph: Robert Estall Photo Agency/Alamy

My sister was working for Paramount Pictures when I first visited Soho as a wide-eyed teenager. The place had been a home for the film industry since at least 1908, when colour film pioneer Charles Urban moved into offices on Wardour Street. In the 1970s, all the big film companies had offices here.

Dirty, smelly, noisy Soho was an unbelievably exciting mixture of pubs, restaurants, cafes and markets. And the people! Spotty, chain-smoking youths wheeling handcarts piled high with film cans narrowly avoided being hit by taxis as the most multinational and multicultural mix of people I’d ever seen surged around the streets.

But let’s face it, for a teenage boy, Soho had one other key attraction: it was very, very naughty. Red lights were everywhere and every other entrance seemed to be a strip club, massage parlour, sex cinema or sex shop selling magazines and 8mm home movies. Displays inside and outside the shops, sometimes plastered on entire walls of buildings, were as graphic as the law – or rather, the notoriously corrupt “porn squad” of the time – would allow.

When I started as a reporter on the film industry trade paper Screen International,the area was still dominated by the sex trade. By the mid-1980s, things were beginning to change. Westminster council, under pressure from some high-end residents, began clamping down on the sex trade, refusing to renew licences for sex shops and closing the many illegal video shops that had sprung up to capitalise on the new VHS boom.

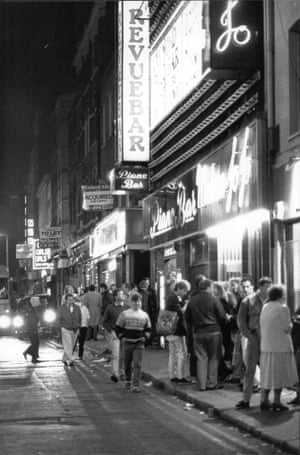

Brewer Street, 1988. Photograph: Rex

Within five years, the gay community had started taking over empty shops and bars, and from the flat where, as an independent film producer, I now lived and worked, I saw the transformation of Old Compton Street in the 1990s into a vibrant hub of cafes and shops fuelled by the “pink pound”.

Old, louche Soho carried on in the shape of pubs such as the Coach and Horses and the York Minster (now called the French House), clubs such as Gerry’s and the Colony Room and illegal drinking dens. New, louche Soho showed its bleary face in the wave of contemporary clubs such as the Groucho, Blacks, the Union and Soho House. An evening out for me usually lasted from 7.30pm to 7.30am and involved walking less than a hundred yards, as there were just so many places to drop into, with so many extraordinary people to meet.

Soho has always been a village and historically it’s been a village full of low-lifers and high-lifers, romantics and realists, drunks and dreamers, sex workers and bar workers – every walk of life is represented. But one thing binds us together – a ferocious loyalty to the place.

Even though the alleyway on which I live could accurately be described as “dodgy”, it still feels the safest place I’ve ever called home. People have always looked out for each other in Soho, and if a girlfriend was ever bothered by a random guy as she was unlocking the door to my house, you could bet that a local dealer, working girl or strip-club caller would be at her side like a shot, checking that she was OK.

When I moved into the flat, the restaurant owner below my old place organised trollies with the local market workers to shift my stuff down the road. When I was locked out once, one of the local pimps rounded up some of his clients to join me in yelling for someone to come down and let me in.

Of course, there’s always been a dark side and even my somewhat rose-tinted spectacles allow me to acknowledge that. But to date, despite the best efforts of the police and gentrifiers, no one has been able to prove that a Mr Big is moving behind the scenes of the sex business, in the way that the so-called Maltese mafia ran the vice trade in the 1950s and 60s. The women I know are hard-working, self-employed girls and their treatment was deplorable during the questionable police raids at the end of 2013 (which happened to coincide with a Westminster council meeting to vote on the demolition of some historic buildings and construction of a steel-and-glass eyesore that even the council’s planning department thinks is oversize and poorly designed).

That raid really marked the latest phase of gentrification in Soho, where it seems like every other building is being gutted or demolished to make way for expensive flats, most likely to be bought by overseas investors. Much of this gentrification is fuelled by developments such as Crossrail 1 and 2 (the latter of which threatens to destroy the Curzon Soho and inflict years of massive construction work in the heart of the theatre district). Much of the gentrification is due to plain greed overriding any kind of social commitment or social policy.

Rents are soaring and many small businesses are being forced out. My village is turning into Any City Centre Anywhere, with identikit gimmicky pop-up hipster venues replacing cafes, restaurants, bars and shops that have been in situ for years. And it remains to be seen whether replacement music venues such as the “new” Madame JoJo’s when it opens in Walker’s Court will be able to provide a similar experience at similar, inexpensive prices to the old one. Our hardware store, which closed last week while a new hotel is built above it, will not be back in two years, having been told that its rent will have doubled, if not tripled, by then.

It was with all of this in mind that I became one of the founder members of Save Soho, whose call to arms is “Inclusive, not Exclusive”. In the short time it has existed, and thanks in no small part to the high profile of fellow committee members Benedict Cumberbatch and Stephen Fry, the organisation has focused attention on the impact of the area’s ongoing gentrification and already helped to chalk up a number of small but significant victories, such as saving Rupert Street’s historic Yard Bar from poorly conceived and destructive “development”.

No one opposes change. I hope my little history of the Soho I know and love demonstrates that this area is perfectly able to move with the times. But change cannot simply be about profit for a handful of people.

And if change results in the wholesale demolition of the very things that make Soho unique and original, rather than finding ways to respect and build on this unique square mile’s existing history and heritage, then I, along with my Save Soho colleagues, will continue to lobby and campaign as loudly as we can.

Colin Vaines is a film producer and long-time Soho resident.

The 1950s

Polly Perkins on… performing at the Windmill theatre

The Windmill girls. ‘It was like a boarding school,’ says Polly Perkins, ‘where you danced and took your clothes off.’ Photograph: Rex

My father was an actor/manager at a club opposite the Windmill theatre; he worked for Paul Raymond sometimes. When I was 15 he told me: “Go and do an audition at the Windmill” and I did. I knew nothing about the place – I had no idea the audition would involve taking my clothes off. But there was an amazing atmosphere there; it was the warmest, kindest place. Everyone was really lovely and an older Windmill girl would show you what’s what. Iris, who took me under her wing, we’ve been friends all these years.

I didn’t have to take any clothes off for the first few months. I was 16 when I did. I was dying [of embarrassment] that first time; I’d always been very shy. The lord chamberlain wouldn’t allow a nude person to move in a theatre, so you had to stand very still. I had to do it reasonably regularly after that but I got used to it. It wasn’t all nudes; they had fantastic tap dances and ballets, brilliant performers and comedians… I can’t tell you how amazing it was. We had to be there at 11.15 in the morning and it went on till 10.30 at night. We’d do six shows in a day. A lot of people – well, they were all men – they’d stay the whole bloody day sometimes, with either a newspaper or a bowler hat on their knee; I’ll say no more.

We used to go to a cafe next door called the New Yorker to drink lemon teas, and the coffee bars: Heaven and Hell, Act One Scene One (that’s where the actors would go) and the 2i’s, where the rock’n’roll musicians were. Everybody there was in love with my friend Perrin from the Windmill. Tommy Steele wanted to marry her, so did Billy Fury. She was beautiful; the girls from the Windmill entered her into a Brigitte Bardot lookalike contest. They were like that, the girls.

We’d go to Berwick Street market, where they had the barrow boys selling fruit, and they were absolutely lovely. It wasn’t all that whistling or anything suggestive, it was: “How you doin’, darlin’?” The Kray twins would be up having a drink in Soho but whatever they were doing, it wasn’t happening in Soho. You could talk to anyone – you can’t do that now. Even the girls at the strip clubs, they were all lovely too, you’d see them running up Old Compton Street with a little bag full of feathers…

We were very glamorous, but it wasn’t something we felt. We were self-critical, all of us. But the older girls were so nice to the younger ones, they’d help with the makeup and things; it was like a boarding school, where you danced and took your clothes off! Though not everyone did; Iris was too good a singer and they’d have lost her [if they’d made her]. But I was too young to argue and too grateful for the job. I started out on £12 a week in 1959 and every year I got a rise. When I left I was on £16-£17 a week, which was a lot of money then.

The Windmill theatre closed a couple of years after I left. I don’t think I’ve seen anything like it before or since. It taught me everything I know about my stagecraft; the discipline, getting on with people, dressing-room politics and the loyalty of friends.

Interview by Corinne Jones

Molly Parkin on… drinking at the Colony Room

Francis Bacon, one of the original members of the Colony Room. Photograph: The John Deakin Archive/Getty Images

The place in Soho that started it all off for me was the Studio Club in Swallow Street. I’d gone there with my friend Betty, with whom I was sharing a basement flat in Earl’s Court. She was very beautiful and fashionable and I was very arty. I used to wear black and put calamine lotion on my face, very pale, and lots of black pencil around my eyes. So there was a nonconformist look about me. All I needed was a slot to fit in. The Studio Club was a place for artists and jazz musicians and it had a tiny dancefloor and an amazing atmosphere to it. It was there I met [the illustrator] John Minton. He was gay and very beautiful and a wonderful dancer – and he was the first one to take me to the Colony Room.

The first time I walked up that narrow staircase I was horrified – it seemed to me so shabby and there were men with faces like I’d never seen before – very lived in, let’s put it that way. The place was rocking. The room was tiny and packed with photographs and bits and pieces and lumpy places to sit and the conversation was loud and the piano was pounding with jazz.

I took to the drink immediately, I couldn’t say no. When I came out on to Dean Street, I couldn’t even walk but I knew that an amazing life had opened up to me. The hangovers were appalling but it did enhance my creativity.

I was very impressed by Muriel [Belcher, the famously rude owner], the way she used swear words in such a beguiling way. You’d bring in somebody that she had not seen before and she’d just look them up and down and say: “I don’t like the look of you cunty, fuck off.” Then she would wink at the rest of us and burst out laughing. She was a very handsome woman: she had a hooked nose, black hair drawn back from her face, very strong, dark eyes and, because of this “don’t care” attitude, everybody adored her. Francis Bacon was passionately in love with her.

I became very close to him in the years between my marriages. He was so kind and attentive and funny. One time he took me to the Golden Lion in Dean Street. Homosexuality was still illegal at that time but this was the place all the gay boys would go to when they arrived in London to meet kindred spirits. I remember Francis throwing all these £5 notes into the air and all the boys were scrambling for them, shouting: “Francis, Francis!” I’ve never seen such adoration.

I stopped going to the Colony Room in 1987 when I found myself in the gutter. I’m 83 now and I’ve been without a drink for 28 years, but those were my precious years. Every single moment that you were there was like being in heaven, because of the jokes and the laughter and the bonhomie. It was like lifeblood to me.

Interview by Joanne O’Connor

The 1960s

John Pearse on… working as a tailor in Carnaby Street

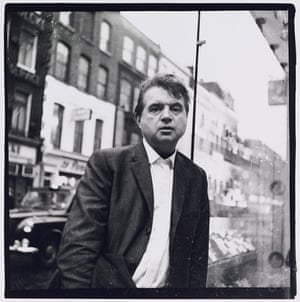

John Pearse and friend in 1966: ‘We were peacocks in sharp-as-a-knife tailoring.

I left school aged 15 because I wanted to be in Soho. It was 1961 and my first job was on Wardour Street, upstairs from the Marquee Club, in a print factory. I was a lithographic artist, but I only lasted about eight weeks because I couldn’t stand the noise of the machines clunking. I wanted a calm job, so I thought I’d become a tailor and get some peace. And also I’d get the suit I wanted to wear that I couldn’t afford to buy. I decided I’d learn to make it.

There was a whole band of us, various peacocks parading around in sharp-as-a-knife tailoring. The Who, I think, Keith Moon, Brian Jones, people like that. We gravitated around the Flamingo Club, the Roaring Twenties and especially the Scene Club in Ham Yard, off Great Windmill Street. Of course the Stones played there, the Animals, anyone who was anybody was playing there. When Kennedy was shot in 1963, I remember they closed the Scene Club in honour of him that night.

Carnaby Street was a dirt track then, but there was John Stephen and Donis and these gay outlets, let’s say. They were the only places you’d get French imported stuff from – the hipster trousers and matelot shirts – which we liked. And the famous Levi’s shop was on Argyll Street, next door to the Palladium. You’d know if they had them in stock because you could smell the dye when you walked in

When Time magazine ran its London: the Swinging City issue in 1966, Carnaby Street was gone up in smoke for us. It had become vastly overpopulated and commercialised by then; John Stephen had more or less the whole street and a lot of the indigenous little shops had gone. We were on our own route on the King’s Road in Chelsea, with our shop Granny Takes a Trip. My tailoring expertise served me very well over there and then Carnaby Street started copying all those things we were producing.

I stopped making suits for a few years – mostly working in film – but came back to Soho in 1986. I loved this building in Meard Street and I thought I’d do film production in the basement and sell a few suits to supplement my income. There was a pool table, so it was quite a clubby atmosphere, and for a couple of years I would have been the most exclusive, discreet tailor in the world, because you really had to know where to find me. It was all word of mouth; classic English tailoring, lots of vintage fabric. Jack Nicholson was a big client in those days, Hollywood people and Jagger, lots of different people.

I’ll stay in Soho until I get kicked out; I won’t get bored with it. It’s such a vibrant place and it always seems to evolve. It never stands still, so you either go with it, or you get off.

Interview by Tim Lewis

From the archive: George Melly on… the rhythm and blues invasion

The Who on stage at the Marquee in 1967. Photograph: Ray Stevenson/Rex Features

Over the last year the British version of rhythm and blues has elbowed the Liverpool beat groups, always excepting the Beatles, out of the charts – and it looks as if it’s here to stay for a while.

Like most pop trends R&B started in the clubs, but it’s learned something. The top beat groups, and the top trad bands before them, priced themselves out of the clubs and played concerts only, but nearly all the R&B groups continue to play the clubs even after they’ve made the top 20. As a result they are holding their public and their music has not yet ossified.

British R&B today is a wide river, but it has two sources. One springs from traditional jazz, the other from modern. In Wardour Street are two clubs which could lay claim to promoting these tributaries. They are the Marquee on the traditional side, and the Flamingo on the modern.

The Marquee was originally in Oxford Street. In those days it featured all kinds of jazz but relied on trad to pay its way. Ironically enough, it was Chris Barber, the traditional band leader, who introduced the R&B viper into trad’s bosom. Interested in all forms of black music, he instituted in 1962 an experimental evening of R&B featuring Cyril Davis and Alexis Korner.

By the time the Marquee moved to Soho in 1964, the music was big enough to justify two evenings a week. On R&B nights at the Marquee it’s a very young audience and, if one of the groups gets into the hit parade, it’s a big one. It seems bright and lively, but they neither know nor care about the history of the music, only about its local heroes. An admirable policy of the Marquee is to bring over the great black blues singers whenever possible.

Up the road at the Flamingo there’s an older crowd. The Flamingo was one of the midwives of modern jazz in this country, but two and a half years ago an ex-Billy Fury sideman called Georgie Fame introduced a Sunday afternoon session of modern R&B, accompanying himself on the Hammond organ. A year ago the club moved over to an almost exclusively R&B policy.

This is an edited extract of an article that originally appeared in the Observer on 28 February 1965

Writer and agony aunt Irma Kurtz on… the search for bohemia

Irma Kurtz, centre, with Muriel Belcher and friend at the Colony Room Club. To order The Colony Room Club 1948-2008: A History of Bohemian Soho by Sophie Parkin visit thecolonyroom.com.

I came to London in the 60s in search of bohemia. I was escaping from the conventional destiny that was laid out for me in America, which was to marry a lawyer, maybe a doctor, in Connecticut, to live in the suburbs, have three children and two cars. I’d found it in the West Village in Manhattan and on the left bank in Paris and when a friend took me to the French House in Soho, I thought: “Thank heavens they have it here too.”

We use the word “bohemia” very easily but what it meant to me was an area where the affluent mix with the poor, where the gay mix with the straight, where long ago women could mix with men and be listened to. It’s a strange area of equality among people who are not generally considered equal and where celebrity is practically invisible. In bohemia, nothing matters but your conversation and your ability to talk to others.

The French House was everything I’d dreamed of. Everyone was leaning at the counter, no one was sitting down, everyone smoked, the mix was so welcoming. The main thing that bohemia had was a curiosity about newcomers, it wasn’t prejudiced against anyone, except of course fascists and bigots.

One of the hardest things for a young woman of any time to find is a place where she’s comfortable going in on her own. But it didn’t take long before I knew I was going to recognise people and I made a best friend, Jeff Bernard. He had a corner, his corner, and a circle of people around him, his court, because he was so funny. He wasn’t easy and he was a hell of a drinker and most nights I’d leave him to go back to where I was living in Shepherd’s Bush.

He once said to me: “Oh Irma, I’m so glad we never did the deed because it would have spoiled a wonderful friendship.” And it was.

I was with him a lot at the end and so was Norman Balon, the landlord of the Coach and Horses. He was so good to Jeffrey. When he was bedridden, he kept him in food and made sure the flat was clean. He’s not a cheerful person, Norman, and he used to yell at people in the bar, but he was a good guy. There was a certain kind of bar person – characters such as Norman and Muriel [Belcher] – sharp-tempered, sharp-witted, they were the guardians of bohemia. If people were rude, if they were arrogant, if they were bigoted – things that have no place in bohemia – they’d get them out.

I stayed in Soho long enough to see the end of the great bars. I remember going into one of my favourite pubs and there was a television screen up, and I thought “uh-oh”. This was not long before I moved out. I remember thinking: “I’m not leaving Soho, Soho is leaving me.” When I go back now I’m very homesick for what it was. I don’t know where you go to find bohemia now. I asked one of my young friends and she looked at me and she asked me seriously: “Have you tried online?” JO’C

The 1970s

Keith Hehir-Lynch on… being a teenage ‘runner’ for a stripper

‘Two old men were fighting over her satin knickers.’ Photograph: Mark Mawson/Robert Harding/Rex

It’s 1973. There is an oil crisis in the Middle East. The IRA are blowing up anything and everything. Richard Reid the shoe bomber has unfortunately just been born and JRR Tolkien has unfortunately just died. There is a secondary banking crisis that causes negative equity in the housing market and the UK has finally admitted to being within 30 miles of the near continent and has joined the European Economic Community. A new value added tax has been stuck to everything, the Conservatives are in power and Sunderland only go and beat Leeds 1-0 in the FA Cup final.

It was against the backdrop of these events that I tripped and fell on a feisty and now angry stripper on a chilly and crisp November afternoon just off Soho Square in the West End of London…

After being told something clearly physically impossible to do by myself, I offered to carry her heavy bag as an apology. She accepted and pushed me into the club shouting at me to hurry the fuck up. I passed the big fat Greek doorman and followed her down the red-lit stairs. “Look after my bag,” I was instructed with a long red finger nail pointing within an inch of my eye. She also warned me not to move. So I didn’t.

Another reason I didn’t move was because I was in the second row of a smoky and dark, sparsely attended strip club watching a brightly lit stripper do what strippers do. As I hadn’t seen many naked women in the flesh, this became an instant highlight of the previous four days.

My next surprise was Cathy. A brunette, pale-skinned and curvy, full lips with the reddest of lipstick, was now wearing a blonde afro wig and on stage taking her clothes off to Walk on the Wild Side by Lou Reed. That song still stops me in my tracks at whatever I’m doing. I remember her perfectly arched back and fine arse moving and gyrating to it.

I felt compelled to make myself useful for the privilege of watching her unbelievably perfect bottom and picked up the knickers and basque thrown to the side near the front of the small stage and I put them in her bag. Within minutes, Cathy the stripper, now minus the wig, was marching towards me on the way out of the door. She grabbed the bag I was holding and sped off past me. I followed her out.

She watched me collect her outfit and gave me 50p, thanked me and rushed off. I ran after her and asked where she was off to next. She was already speed walking to another strip club 100 yards up the street, one of about 15 or so she would perform in rotation most nights.

So the deal was done. Cathy often called me a cheeky little bastard, but I got £2 a night from her and in turn saved her money buying new outfits because either the top or the bottoms were nicked during a performance by the other girls or snatched away by paying punters wanting souvenirs. I was a goalkeeper of knickers, the comedic fighter of old men to rescue a bra. I even ended up on my arse on one occasion with two old men fighting it out over her black satin knickers. I say “old”, but anyone over 30 would have been old to my 14-year-old self.

I’d like to think she regales her grown-up children with tales of her exploits today. Maybe she tells the tale of a young man who she once paid to pick up her knickers. Maybe she has never ever told a living soul of her life as a stripper. Maybe…

@Mr_Taxi_Man

Chris Sullivan on… the best nightclubs of the decade

Johnny Rotten, right, and Sid Vicious of the Sex Pistols at the Marquee Club in 1977. Photograph: Dennis Morris

I’ve probably spent more time in Soho than any other place on Earth. My first visit was to Crackers nightclub on Wardour Street in September 1975, aged 15. With its exceedingly flamboyant gay, straight, black and white clientele, united by their love of US underground funk music, there was nowhere like it in the UK and, as I soon discovered, exactly the same could be said of its locale.

Subsequent trips further fuelled my enthusiasm. We caught an early Sex Pistols gig in the El Paradise strip joint on Brewer Street in April 1976, imbibed chemically enhanced punch and lost ourselves, only to resurface the next afternoon on a bench in Soho Square. After that came Louise’s, the Sapphic nightspot on Poland Street that we, at first, thought a rather straight disco full of blokes in suits, before realising they were all women. Accordingly, they didn’t bat an eyelid as the Sex Pistols, the so-called “Bromley contingent” and assorted bondage-clad youth invaded their club.

In October 1978, my old partner in crime, fellow Welshman Steve Strange, invited me to his weekly Bowie night at a club called Billy’s on Meard Street – a tiny paved street full of street walkers, red lights and brothels. The club, replete with sticky carpets, foul toilets and bad drinks, was usually populated by hookers, androgynous rent boys and moody gangsters. On a Tuesday, though, it was given over to our gang of former punk-rocking Bowie fans – among them the likes of Boy George, Marilyn, Siobhan Fahey, Marc Almond and Philip Sallon – who, with a newfound love of electro music, would soon put the cat among the pigeons. In truth, Soho was the only place for us. Nowhere else would have us.

The following year, I was accepted into Saint Martins College of Art on Charing Cross Road to study fashion. For many, Saint Martins was as much about the social life as it was about studying and Soho was thus enriched by the students, especially the fashion brigade, who sucked the lemon dry. We’d spend lunchtimes in the French House or the Duke of Cambridge (or my favourite, Ward’s Irish House beneath Piccadilly) and hang out with actors and journalists and then, when the bars shut at 2.30pm, we’d try and wangle our way into the morally decrepit Colony Room on Dean Street. The image of Stephen Linard in gold lamé Elvis suit, bleached quiff and eyeliner next to Kim Bowen, with her foot-high Stephen Jones head-dress and silent movie star makeup, propped up between Francis Bacon, Molly Parkin and George Melly, is not easily forgotten.

Above all, Soho was hilarious. One lunchtime I saw two thoroughly androgynous male Saint Martins fashion bods come to blows over a piece of gold lame in the bargain bin at Borovick Fabrics. Jeered on by the market lads, the fight was broken up by a middle-aged prostitute who looked like a chemically abused Diana Dors.

When too broke to hang out in pubs, we students would often duck into the Academy arts cinema on Oxford Street and catch Scorsese’s Mean Streets and Truffaut’s 400 Blows for a couple of quid, while book shops like Foyles fulfilled one’s every literary need. It was against this backdrop that I opened my own Monday-night soiree in 1980 at the St Moritz, with Robert Elms, Graham Smith and Steven Mahoney, which was packed from day one. Subsequently, I partnered Steve Strange and Rusty Egan for a club called Hell in Covent Garden, did a long-running Tuesday at Le Kilt in Wardour Street, and then in 1982 opened the Wag at 33 Wardour Street, which I ran for 18 years.

Soho was then a dodgy red-light district, which was why so many of us were given nights to run. Soon they blossomed all over Soho, playing soul, funk, reggae, African music, goth, punk, mod, electro, Latin and jazz, and the area was jumping again. Young bands, DJs, graphic designers, painters, artists, film-makers and poets all found clubs in which to display their wares and every night of the week there’d be a handful of after-hours pubs that serviced trendies, trannies, hookers, villains and plain old club workers.

After the Wag came Soho Brasserie, the Groucho, Soho House and the march of haute cuisine, which – always the first sign of an area’s creative decline – is followed by gentrification, increased rents and a general loss of soul, all of which many of us are fighting against.

Soho is the pulsing Queen Bee of London. We have to look after it.

The 1980s

Peter Dowland on… being one of the young guns of hairdressing

The Cuts salon, ‘a community centre for weirdos’, counted Bowie among its customers. Photograph: Getty Images

I joined Cuts in 1985, aged 21, just after it moved from Kensington Market to Frith Street, next door to Bar Italia. We were the first anti-salon. Even just walking past, it looked so different. The energy in there was crazy – Boy George called it “a community centre for weirdos”. David Bowie came, Boy George, Neneh Cherry, Jean Paul Gaultier. Bros were sent to us by their record company. They had perms and long hair and we just shaved it all off and gave them quiffs. It produced tears on the day. But no one was ever treated any differently. Maybe Michael Hutchence would ask to have his hair cut in the basement to avoid the paparazzi. But once down there, we’d just hang out. Everyone was really into the music; we’d be avid consumers of the latest beats and hip-hop from America. We’d always be the first guys to have it, so there was a real energy of discovery all the time.

Cuts’s original founders James Lebon and Steve Brooks were part of the Buffalo fashion collective. It was a synergy of like minds working in design, music, photography. They consistently put out groundbreaking images: macho but camp, feminine but hard. I told them I wanted a job assisting the stylist Ray Petriwho created the Buffalo Boy look. James suggested I start by cutting hair with them. And 30 years later I’m still here.

At first we just rented two chairs – the other hairdressers were two old Italian boys. But we got busy pretty quickly. We were the young guns. The whole film industry and nightlife was here. It was the can-do era. People would go: “Right. I’m going to be a video director” and just do it on whatever budget you could scrape together. Everything felt possible. Music was about two turntables and a drum machine – using other people’s records as instruments and repurposing them. It was creative salvage, a bit like Tom Dixon’s furniture. We had loads of his pieces in the shop – magazine racks made out of manhole covers.

Things weren’t exposed so quickly, so you were able to build your thing without being in the glare of the media. I think kids have a hard time now – whatever little thing they’re getting into is up online having the life sucked out of before it’s even had time to learn to walk.

People tell me it was really intimidating going into the salon for the first time – but as soon as you were through the door you realised everyone was very nice. It wasn’t contrived cool. It was just the chemistry of the people who were there. Hairdressing had a very set image then and James and Steve wanted this quite hetero, sexy feel.

The downside now is that every hairdresser has full-sleeve tattoos and looks like a Hells Angel. When I walk round Shoreditch, I think: “Gosh, we’ve created a monster.”

Interview by Liz Hoggard

The 1990s

The Very Miss Dusty O on… Madame Jojo’s nightclub

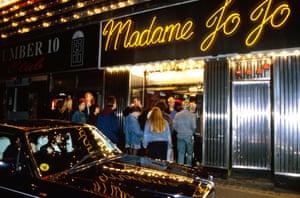

Outside Madame Jojo’s in the 90s. Photograph: Gianni Muratore/Alamy

I came to London from Birmingham in 1989 and got friendly with these people who ran a big club, Bambina’s. They asked me if I’d do the door in drag – it was a fairly new thing at the time and created quite a stir. I’d change my look from day to day: waist-length green dreadlocks one day, the next a shaved head and full makeup. One day, their DJ didn’t show up and I was asked to DJ in the VIP room. I drifted into it, really, and ended up working at places like Bang, Fred’s, the Village, and the Ghetto, which has now been knocked down to make space for that hideous, monstrous Crossrail thing.

Soho became very gay very quickly: in the 90s I’d say it was 90% gay on certain streets. It was a safe place: if you wanted to hold your boyfriend’s hand you held your boyfriend’s hand. I could walk down Old Compton Street in a bikini and no one would bat an eyelid. The crowds were a mixture of the out and fashionable with the underground and sleazy, celebrities mixing with prostitutes, punks and pimps. Everybody was thrown into the melee: it wasn’t corporate, it wasn’t mundane. Now it’s becoming like a creme brulee – bland, all one colour – whereas in those days it was more like a trifle, colourful and glittery.

The Very Miss Dusty O at her Trannyshack night. Photograph: Alamy

Madame Jojo’s was of huge importance to me. Trannyshack, which was the Wednesday nights I ran there, was a very significant part of my life. If you weren’t from London and you imagined what Soho was, that’s what Trannyshack was: a mixture of everyone, gays, straights, drag, transgender, punks, hipsters, pop stars. We never had to advertise. It was a bit like going back to Berlin in the 30s.

All sorts of things used to happen – Grace Jones dancing on tables, Jean Paul Gaultier and Donatella Versace doing the conga in the road outside – it was a very special place. Soho will be more magnolia for its loss.

I think the gay scene has changed. In those days, because there was no internet, if you wanted to be part of a movement you actually had to go to these places. Now all you have to do is click on Facebook to find out exactly what’s going on: you can live almost a fantasy life. I was upset to see Soho change, but other things have arisen in different areas. East London caters for the alternative side of clubbing, with venues like East Bloc and the George & Dragon; Vauxhall caters for the more mainstream muscly gays who want to dance to house music.

When Jojo’s closed last year it was the final nail in the coffin for me. I’d become gradually more disillusioned with the area. I’ve reached my mid-40s, I’m settled down with someone, and your interests change, don’t they? People often say to me: “But you were the queen of Soho for all those years.” Well, yes, and when I left it was my choice. I wasn’t pushed – I abdicated.

Interview by Kathryn Bromwich

John Maybury on… illegal after-hours clubs

One of my great friends and mentors was Derek Jarman and Soho was very much his stomping ground. It was Derek who introduced me to the basics, like going to Berwick Street market, or to Chinatown for a cheap bowl of char siu. There would be all these different worlds that intersected there.

You might luck out and some old queen would take you to L’Escargot for dinner, and there were always different after-hours clubs, such as the Pink Panther. People like Leigh Bowery used to go there – this was when he was just a weirdo on the scene. I won’t go into what sort of things went on in there, but we were regularly raided by the police and everyone would drop everything they had, so there would suddenly be a carpet of substances on the floor and everyone would be marched out on to the street and then, half an hour later, everyone would march back in again and pick up everything they’d left on the floor.

Places like that were so transient: they were there and then they were gone. The place I miss most has to be the Colony Room. I was first taken there as a young punk in the late 70s by the painter Michael Wishart. Francis Bacon was there and I was terrified of him. I had dyed hair and makeup, and, ironically, so did he.

He was very much a hero, which is why I made the film Love Is the Devil. 1995, when I started working on it, was a really interesting time [at the Colony Room] because there was a sudden change of the guard – you still had a lot of the crowd from the 50s and 60s, as well as people such as Sarah Lucas, Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin.

Soho is always mutating. Back then, people moaned about the influx of gay clubs, saying that was a kind of gentrification. Old Compton Street turned into something they didn’t recognise in the 90s. A lot of the old Colony Room crowd resented the imposition of gay culture, because they saw themselves as queers, not gays. They existed at a time when being gay was illegal and they found the gay scene contrary to their code of being.

But what’s happening now is a whole other ball game; places disappear almost overnight. What’s great about London, though, is that despite the property developers, people will always find a new place to gravitate to and then the gentrification virus will creep into that area as well.

Margot Henderson on… the French House pub and its atmospheric dining room upstairs

The French House on Dean Street. Photograph: Alamy

Fergus and I met when I was working at the Eagle [in Farringdon] and he was working at the Globe in Notting Hill. We fell in love and decided we wanted to open a restaurant together. He had a friend called Jon Spiteri, who said that there was space above the French House pub in Soho. We were all regulars, so John spoke to Lesley and Noel [the proprietors] and they were very keen. The three of us were partners there from 1992 before Fergus and John went off and did St John together in ’95. It was a bit upsetting, but Mel [Melanie Arnold, John’s wife] and I became great partners, and it was all for the best. We had all our small children there and manned the French for seven to eight years. We loved it there – it was our baby.

It was a gorgeous pub full of atmosphere, with some great characters. We really felt a part of it. The dining room was small and intimate, we had people proposing there, we had funerals, marriages, everything. We started to do a lot of art events: White Cube had a lot of their dinners there – we did a dinner for Nan Goldin. Mel was living in Broadwick Street and I was in Covent Garden, so we would bring our little kids into the restaurant every day and it was very much family-based; we knew everyone on the street. The woman who used to clean the spanking-mag shop next to Patisserie Valerie used to give all the kids teddy bears. Everyone just knew everyone, it had a real village atmosphere, and I think the French House dining room brought that with it as well. Lucian Freud would come up and sit in the kitchen and flirt with all the young chefs… Lots of artists came, all the local naughty people – people who love to eat and drink and have long lunches.

Our three children all went to Soho Parish primary, a really lovely school in the middle of Soho. It was very small, and really suffered from funding, so Mel and I had an art auction for it at the Groucho and sold £180,000 worth of art, which everyone was in absolute tears about – it was pretty amazing! Damien Hirst did his first skull, Sarah Lucas did a piece – it was all very exciting.

Bar Italia was very good with children; it’s been our place for ever. I think it saved me, actually. Every morning, I’d head straight there and read all the papers with a baby on my front before going into work.

We were very sad to leave. We put our hearts and souls into it and we didn’t mind not making lots of money. It was just so hard not to have a business in Soho. There’s an atmosphere of people looking out for one another there; it’s a friendly, happy place.

The 2000s

Michele Wade on… Soho’s cafe culture

Michele Wade outside Maison Bertaux: ‘Jeffrey Bernard would sit upstairs and fall asleep in his chair.’ Photograph: Rob Greig/Rex

I’ve been involved in Maison Bertaux since I was about 17, in the late 70s. I fell in love with Soho, but especially in love with the shop, the whole atmosphere. I started as a Saturday girl, then I was a waitress and then I went to study at Rada. I made a little bit of money in acting, so when Mme Vignaud, my boss, said she wanted to sell the business, I bought it from her. I was 25 or 26.

There weren’t so many places in Soho then where you could have tea, coffee, conversations. The pubs used to close between 3 and 5pm, so we got a slightly different clientele because of that… I remember Jeffrey Bernard used to come in sometimes after drinking at the Coach and Horses at lunchtime. He’d sit upstairs and fall slightly asleep in his chair and then go to the pub again afterwards. We also used to have the art school [Central Saint Martins] up the road and the students used to come here to sit upstairs and draw… it was relaxing for people. Alexander McQueen was a real regular, just gorgeous. We knew him quite well.

Now my sister, Tania, and I run a little art gallery upstairs. We’ve got Noel Fielding’s artwork up there, he’s really charming. Clients? We’ve had all sorts: Derek Jarman was always coming here, he was a marvellous person; Steve McQueen, Howard Hodgkin, Grayson Perry…

The big thing of Soho is the freedom for people to be who they are. I’ve got a [male] customer who comes in dressed as a woman and no one pays any attention. I think people worry the corporations might squeeze down that freedom. In Soho, there’s space for everybody, but other burgeoning areas – like Shoreditch, Dalston, Peckham – they’re not as inclusive. Maybe that’s why a lot of businesses can coexist in Soho.

We’re frightened about the rent going up so high that we can’t afford to be here, but I try never to be scared. When I first took over Maison Bertaux, we only did one type of tea, but now we do about 20; we only did cafe au lait, but now we do all the coffees. Soho is always changing and you’ve got to adapt and be attractive to people who are enjoying the change. But people have to help each other to make sure there’s room for everyone.

The vicar from the church nearby comes to get his ham-and-cheese croissant every Saturday and Sunday and we’ve got a lot of irregular regulars from all over the world who come to Maison Bertaux when they’re in London. We also have quite a few people coming in who aren’t homeless, but who’ve fallen on hard times, so we give them something to keep them going.

Soho’s always had that history of having different kinds of businesses and restaurants, and I think that’s what makes it unique, because every building’s had a restaurant in it before and before that and before that… Everyone over 40 who knows Soho, they’ll have a memory of it. People won’t have those memories of Hoxton, or places like that. CJ

Tim Arnold on… why we started the Save Soho campaign

Singer-songwriter Tim Arnold in Blacks Club, Dean Street, in one of Soho’s oldest buildings. Photograph: Iain G Reid

I got a place at St Martins to study fine art in 1994, but then I got snapped up for an eight-record deal by Sony. I never went to art school. I was living on Charing Cross Road, Sony were on Great Marlborough Street and I was going to places like Cafe Bar Sicilia, the Atlantic Bar and the Astoria, so Soho was my world. I was hanging out with people like Jarvis Cocker and Alex James from Blur.

In 2010, I decided to write a book, called Soho Heroes. I’ve interviewed over 100 people: tailors, restaurateurs, DJs, remarkable characters I’ve worked with and lived alongside all these years. And then I started working on a concept album, The Soho Hobo, which is really just me trying to understand what it is about the place that I love so much. As I was working on those two projects I kept seeing Soho disappearing bit by bit.

And then Madame Jojo’s closed and I realised it isn’t enough to sing about Soho any more; you’ve got to do something. That’s when I wrote to Boris Johnson and enlisted Benedict Cumberbatch who in turn enlisted Stephen Fry to sign the letter. I set up the Save Soho website so that people who felt the same could come together, and then suddenly we were getting 25,000 hits a week.

It’s hard enough for new artists starting out, without the small venues closing down. And with somewhere like Denmark Street, young kids want to walk down the street where the Rolling Stones recorded, they want to possibly bump into Jimmy Page buying a guitar. They want to have that feeling that I had when I was in Madame Jojo’s and rubbing shoulders with the likes of Jarvis Cocker – “I must be in the right place because all the guys who inspire me are here.” There’s a passing of the baton and, culturally, there’s a responsibility to keep those venues inclusive and let them continue.

For 400 years, Soho has allowed people to think differently, from Karl Marx, who wrote Das Kapital in Dean Street, right up to Paul O’Grady, who was doing the kind of comedy that would have got him thrown out of any other place in England. It’s a national platform for innovation and creativity, and it’s under threat from people who want to turn it into a rich person’s playground.

As a singer-songwriter, I have been ignited by the spirit of the area. I write at least a song every day and I usually do it looking out of my window in Frith Street. I’ve led a very bohemian life, sacrificing everything that’s respectable for creativity. I wouldn’t have had that life anywhere else. JO’C

Laurence Lynch on… much-missed institutions

Laurence Lynch. Photograph: Alpha Press

There is an energy in Soho that sends people mad. When I first moved to Soho about 25 years ago, it was not only the madness that interested me, it was the small independent business people; they still do, the grafters who keep our community alive with their warm welcomes and industry. I love pubs and that was where I was able to meet people, make friends and pick up work. It was all word of mouth – that was how Soho worked.

After many years, I was taken to the Colony Room, 41 Dean Street, where I became a member. To me, it was the centre of the centre. I spent a year of my life with Sebastian Horsley, Hamish McAlpine, Ian Freeman and others trying to save it. Change of use was turned down, but the landlord appealed and now the Colony is a one-bedroom flat. It is not the only Soho treasure lost in the past 10 years. Here’s a roll call:

• The New Piccadilly restaurant in Denman Street, voted the joint best cafe in London, demolished to build the Ham Yard hotel complex.

• The Bath House pub, Dean Street, demolished, Crossrail.

• The Black Gardenia, Dean Street, demolished, Crossrail.

• The Astoria music venue, Charing Cross Road, demolished, Crossrail.

• The Intrepid Fox, Wardour Street, world-famous rock pub, now a burger bar.

• The Devonshire Arms, Denman Street, now Jamie’s Italian.

• The Soho Pizzeria, Beak Street, now a burger bar.

• The King’s Head and Dive Bar, Gerrard Street, demolished, Chinese restaurant.

• The Lorelei Italian restaurant in Bateman Street, there for about 40 years, replaced by a restaurant that lasted six months.

And now it’s the turn of Berwick Street market’s adjoining shops, which are being destroyed to make way for another hotel. Lastly – for now – the plot on which Curzon Soho cinema stands in Shaftesbury Avenue is now being eyed up for Crossrail 2.

That is a lot to take out of a small area in such a short time. The living thing that is Soho is having its limbs removed. But we’re not ready to put the keys back through the letterbox and turn the lights out yet. Now, whose round is it anyway?

Laurence Lynch is a playwright and plumber. His play, Burnt Oak, runs until tonight at the Leicester Square theatre

The 1960s Counterculture in Britain and America – a talk by Kenny Wilson at Secular Hall, Leicester on October 6th 7.00 p.m.

I am doing a talk at The Secular Hall, Humberstone Gate, Leicester on the 6th October 7.00 p.m. Hope you can make it. It should last about an hour including audio and film clips, and there will be an opportunity for questions and comments at the end. Also, in the spirit of the time, it is free.

Counterculture Talk Leicester October 6th at Secular Hall

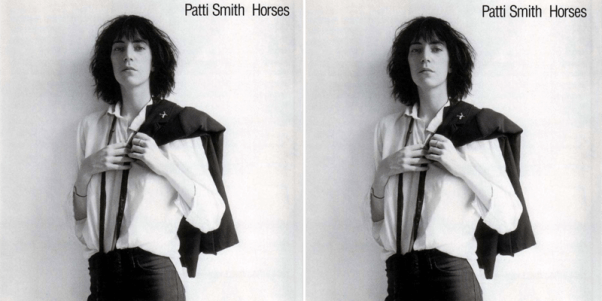

Camille Paglia on the Iconic Cover of Patti Smith’s Horses | Literary Hub

Source: Camille Paglia on the Iconic Cover of Patti Smith’s Horses | Literary Hub

“THE MAPPLETHORPE PHOTO SYNTHESIZES MY PASSIONS AND WORLD-VIEW”

In 1975, Arista Records released Horses, the first rock album by New York bohemian poet Patti Smith. The stark cover photo, taken by someone named Robert Mapplethorpe, was devastatingly original. It was the most electrifying image I had ever seen of a woman of my generation. Now, two decades later, I think that it ranks in art history among a half-dozen supreme images of modern woman since the French Revolution.

I was then teaching at my first job in Vermont and turning my Yale doctoral dissertation, Sexual Personae, into a book. The Horses album cover immediately went up on my living-room wall, as if it were a holy icon. Mapplethorpe’s portrait of Patti Smith symbolized for me not only women’s new liberation but the fusion of high art and popular culture that I was searching for in my own work.

From its rebirth in the late 1960s, the organized women’s movement had been overwhelmingly hostile to rock music, which it called sexist. Patti Smith’s sudden national debut galvanized me with the hope (later proved futile) that hard rock, the revolutionary voice of the counterculture, would also be endorsed by feminism.

Smith herself emerged not from the women’s movement but from the artistic avant-garde as well as the decadent sexual underground, into which her friend and lover Mapplethorpe would plunge ever more deeply after their breakup.

Unlike many feminists, the bisexual Smith did not base her rebellion on a wholesale rejection of men. As an artist, she paid due homage to major male progenitors; she wasn’t interested in neglected foremothers or a second-rate female canon. In Mapplethorpe’s half-transvestite picture, she invokes her primary influences, from Charles Baudelaire and Frank Sinatra to Bob Dylan and Keith Richards, the tormented genius of the Rolling Stones who was her idol and mine.

Before Patti Smith, women in rock had presented themselves in conventional formulas of folk singer, blues shouter, or motorcycle chick. As this photo shows, Smith’s persona was brand new. She was the first to claim both vision and authority, in the dangerously Dionysian style of another poet, Jim Morrison, lead singer of the Doors. Furthermore, in the competitive field of album-cover design inaugurated in 1964 with Meet the Beatles(the musicians’ dramatically shaded faces are recalled here), no female rocker had ever dominated an image in this aggressive, uncompromising way.

The Mapplethorpe photo synthesizes my passions and world-view. Shot in steely high contrast against an icy white wall, it unites austere European art films with the glamorous, ever-maligned high-fashion magazines. Rumpled, tattered, unkempt, hirsute, Smith defies the rules of femininity. Soulful, haggard and emaciated yet raffish, swaggering and seductive, she is mad saint, ephebe, dandy and troubadour, a complex woman alone and outward bound for culture war.

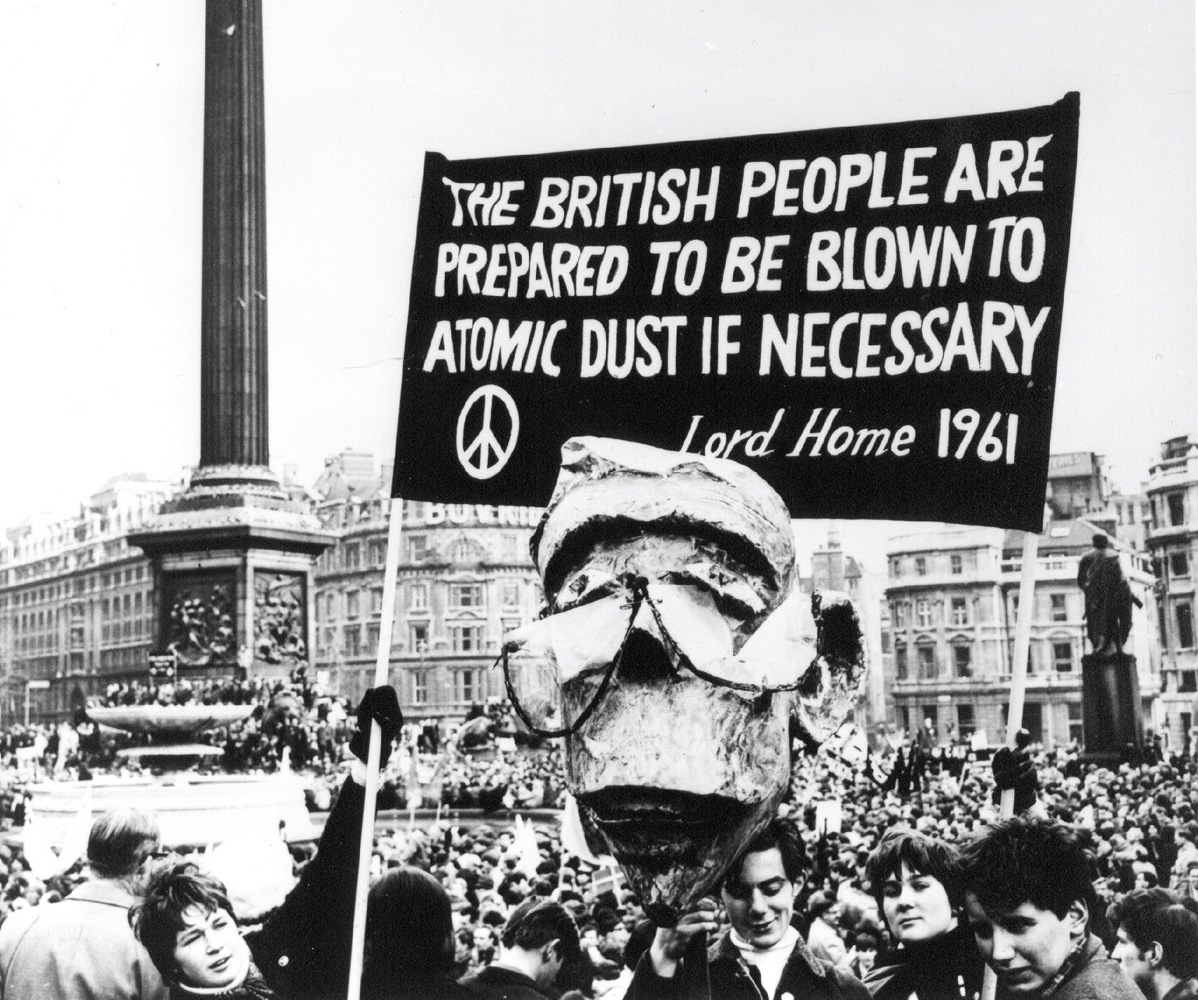

The Untold Story of the Peace Sign

You can find the original of this at Fastcode Design website.

The symbol that would become synonymous with the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) was first brought to wide public attention on the Easter weekend of 1958 during a march from London to Aldermaston in Berkshire, the site of the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment. The demonstration—the first large-scale anti-nuclear march of its kind—was organized by the Direct Action Committee Against Nuclear War (DAC), one of several smaller groups in the U.K. that would go on to form CND. Some 500 symbols were held aloft by protesters as they walked the 52 miles from Trafalgar Square, which suggests that the organizers were aware of the need for both political and visual impact. The fact that, in the form of Gerald Holtom, they already had a professional designer and graduate of the Royal College of Art on board perhaps explains why the symbol achieved immediate success, as well as the swiftness with which it was officially adopted by CND a few months after the march. Holtom was a conscientious objector (during World War II he had worked on a Norfolk farm), and also an established designer. He had created designs as diverse as fabrics based on west African patterns from the late 1930s and a range incorporating photographs of plankton for the Festival of Britain in 1951.

According to Professor Andrew Rigby, writing in Peace News in 2002, Holtom was responsible for designing the banners and placards that were to be carried on the Aldermaston march. “He was convinced that it should have a symbol associated with it that would leave in the public mind a visual image signifying nuclear disarmament,” writes Rigby, “and which would also convey the theme that it was the responsibility of each and every individual to work to remove the threat of nuclear war.”

In a sense, Holtom’s design did represent an individual in pursuit of the cause, albeit in an abstract way. The symbol showed the semaphore for the letters N (both flags held down and angled out from the body) and D (one flag pointing up, the other pointing down), standing for Nuclear Disarmament. But some years later in 1973, when Holtom wrote to Hugh Brock, editor of Peace News at the time of the formation of the DAC, the designer gave a different explanation of how he had created the symbol.

“At first he toyed with the idea of using the Christian cross as the dominant motif,” Rigby explains in his article, “but realized that ‘in Eastern eyes the Christian Cross was synonymous with crusading tyranny culminating in Belsen and Hiroshima and the manufacture and testing of the H-bomb.’ He rejected the image of the dove, as it had been appropriated by “the Stalin regime…to bless and legitimize their H-bomb manufacture.'”

Holtom in fact decided to go for a much more personal approach, as he admitted to Brock. “I was in despair. Deep despair,” he wrote. “I drew myself: the representative of an individual in despair, with hands palm outstretched outwards and downwards in the manner of Goya’s peasant before the firing squad. I formalized the drawing into a line and put a circle round it. It was ridiculous at first and such a puny thing.”

In Holtom’s personal notes, reproduced by peace symbol historian Ken Kolsbun, the designer recalls then turning the design into a badge. “I made a drawing of it on a small piece of paper the size of a sixpence and pinned it on to the lapel of my jacket and forgot it,” he wrote. “In the evening I went to the post office. The girl behind the counter looked at me and said, ‘What is that badge you are wearing?’ I looked down in some surprise and saw the ND symbol pinned on my lapel. I felt rather strange and uneasy wearing a badge. ‘Oh, that is the new peace symbol,’ I said. ‘How interesting, are there many of them?’ ‘No, only one, but I expect there will be quite a lot before long.'”

In fact, the first official series of badges made by Eric Austin of the Kensington CND branch were made of white clay with the symbol formed from black paint. According to CND, these were in themselves a symbolic gesture as they were distributed “with a note explaining that in the event of a nuclear war, these fired pottery badges would be among the few human artifacts to survive the nuclear inferno.”

The symbol itself became more formalized as its usage became more widespread. The earliest pictures of Holtom’s design reproduce the submissive “individual in despair” more clearly: the symbol is constructed of lines that widen out as they meet the circle, where a head, feet and outstretched arms might be. But by the early 1960s the lines had thickened and straightened out and designers such as Ken Garland, who worked on CND material from 1962 to 1968, were able to use a bolder incarnation of the symbol in their work. Garland built on the graphic nature of the symbol to create a play of black-and-white shapes for a series of striking posters. He also used a photograph of his daughter Ruth in the design for a leaflet on which the symbol was used in place of the O in “SAY NO.”

In the U.K. the symbol has remained the logo of CND since the late 1950s, but internationally it has taken on a broader message signifying peace. For Holtom this perhaps came as a bonus since, according to Rigby, he had been frustrated with his original design, which depicted the struggle inherent in the pursuit of unilateral action. Shortly before the Aldermaston march Holtom experienced what he termed a “revolution of thought.” He realized, Rigby writes, that if he inverted the symbol “then it could be seen as representing the tree of life, the tree on which Christ had been crucified and which, for Christians like Gerald Holtom, was a symbol of hope and resurrection. Furthermore, that inverted image of a figure with arms stretched upwards and outwards also represented the semaphore signal for U—Unilateral.”

This last quirk of a symbol that had its message so neatly encapsulated in its design meant it could echo both the frustrations of the anti-nuclear campaigner in the face of political change and the sense of optimism that the task at hand would bring. This was another example of the thinking Holtom would bring to the first march to Aldermaston, which has since become an annual event. Of the lollipop signs he designed for the event, half displayed the symbol in black on white, the other half white on green. “Just as the church’s liturgical colors change over Easter,” CND explain, “so the colors were to change, ‘from Winter to Spring, from Death to Life.’ Black and white would be displayed on Good Friday and Saturday, green and white on Easter Sunday and Monday.”

From the beginning, Holtom’s aim had been to help instigate positive change, to bring about a transformation from winter to spring. Today CND continues to pursue this mission, just as the peace movement does internationally.

This was excerpted with permission from TM: The Untold Stories Behind 29 Classic Logos (Lawrence King). Buy a copy here for $27.

Poster for my lecture at the Bath Royal Literary & Scientific Institution 12th July

More London Coffee Bars of the 1950s and 60s

This is the full unexpurgated Central London Cafe Tour put together for Architecture Week 17-26 June 2005. The tour takes in a range of 1950s and 1960s London cafe styles. As you can see many more have since closed down, overwhelmed by the big corporate chains like Starbucks, Costa and Caffe Nero! Support your independent Coffee Bar!!

The walk starts off in Marylebone, curves along the edges of Bond St, plunges into Soho, then arcs up to Goodge St.

French cafés and US diners have received substantial cultural focus over the decades. But the old style Italian Formica cafes of the 1950s, and earlier, have never been given their due despite their manifest contribution to the (sub)cultural life of post war Britain.

Often dismissed as ‘greasy spoons’, Classic Cafes (those unchanged British working men’s Formica caffs which retain most of their mid-century fixtures and fittings) are actually mini-masterpieces of vernacular 1950s and 1960s design.

Most are now vanishing in a welter of redevelopment. But once, their of-the-moment design and mass youth appeal galvanised British cultural life and incubated a whole postwar generation of writers, artists, musicians, crime lords and sexual interlopers.

For a country that had emerged from World War Two economically crippled and facing the complete collapse of long-held social and political certainties, the caffs became forcing houses for the cultural advance guard coursing through London at the time.

The classic cafes of the 1950s added an impassioned colour to Britain’s post war social, artistic and commercial scene. The mix of cafes, a nascent TV industry and the skiffle cult effectively created a new world order as, from 1963-1967, London dictated youth culture to the world.

Within a decade of the first Soho espresso bar, The Moka at 29 Frith Street, being opened in 1953, London became the world’s hippest city: a ferment of music, fashion, film, advertising, photography, sex, crime, and the avant-garde.

The cafes were, “the first sign that London was emerging from an ice age that had seen little change in its social habits since the end of the first world war. Once the ice began to crack, everything was suddenly up for grabs.” Without them, the unleashing influence of the 1960s might never have been so seismic.

Today, the big coffee combines are destroying classic cafes en masse. By deliberately negotiating exorbitant leases, and raising ‘comparables’ (rent levels used to calculate local rent increases) they are putting competitors out of business at an astonishing rate. This brutal Starbuck-ing of the high street is leading to the wholesale erasure of British vernacular retail architecture.

“The architecture and ambience of [classic cafes] is fast being levelled in a kind of massive cultural, corporate napalming by the big coffee chains… they will not rest until every street in the West is a branded mall selling their wares. Orwell’s nightmare vision in 1984 was of a jackboot stamping on the human face forever. If the coffee corporates have their way, the future is best represented as a boiling skinny latte being spilt in the lap of humanity in perpetuity.” (Adrian Maddox, The Observer, Aug 1 2004)

The loss of London’s classic cafes should be particularly sadly felt. For their far-reaching impact on modern Britain, we owe them, and their founders, an immense debt of gratitude. And a serious duty of care.

Guardian: June 22 2005: ‘Greasy spoon wars’ by Chris Hall

There is no greater call to arms during this year’s Architecture Week (June 17-26) than that of saving the old-style Italian cafes from the 1950s, often disparaged as greasy spoons or working men’s caffs.

Adrian Maddox, author of the definitive book on the subject, Classic Cafes, has compiled a “last chance to see” tour of around 30 of them in London (see http://www.classiccafes.co.uk for details).

Maddox’s concern is with the design and ambience of these cafes, which he finds “bracingly Pinteresque, seedy and despairing”.

The pictures in his book are part Edward Hopper, part Martin Parr.

I met Maddox at the New Piccadilly cafe, the “cathedral of cafes”, in a side street by Piccadilly Circus.

“Everything here is original, apart from the mirrors,” he says. He’s soon enthusing about the Thonet chairs, the three shades of Formica and the extremely rare horseshoe menu.

This Saturday, the cafe can be seen on BBC1 in the new Richard Curtis film, The Girl in the Cafe, with Kelly MacDonald and Bill Nighy.

For Maddox, it’s a war against the big coffee chains whose “policy of extermination” is forcing these cafes out of business.

He reckons that there are only 500 classic cafes left in the UK. Two London cafes, Pellici’s in Bethnal Green and Alfredo’s (now S&M) in Islington, have been grade II listed by English Heritage, but most, if not all, will be gone in a few months or years, he claims.

Is listing the answer? Catherine Croft, director of the Twentieth Century Society, says: “A lot of the charm is in the furniture and the menus and what’s on the tables. It’s popular art, not high architecture. Listing them can only protect the building elements.”

In fact, the owner of the New Piccadilly, Lorenzo Marioni, is glad that English Heritage didn’t recommend it for listing last September, as this would have diminished his potential for selling it, which he still might have to do.

With his landlord demanding ever higher rent, he’s never going to be able to compete with the big chains. “I’d just love to be here at a reasonable rent, serving the local community at a reasonable price,” he says.

Start: south Marylebone High Street (Bond St tube/Baker St tube)

Golden Hind [73 Marylebone Road W1]

Open for nearly forty five years, and owned by the Schiavetta family, this Art Deco Vitrolite chip shop has a full range of classic cafe chairs and tables.

Paul Rothe & Son [35 Marylebone Lane W1]

Untouched, early twentieth century deli and old-fashioned provisions shopwith cafe area featuring unique, folding white leatherette-seating (late 60s vintage). Many archive pictures, and a full history of the premises, are displayed in the windows. (Rothe’s liptauer sandwiches are legendary.)

Marylebone Cafe [58 Marylebone Lane W1]

Plain-style caff on the verges of Oxford St. Good exterior mosaic tile patterning and a big bold nameplate and awnings. Decent booth interior. John and Alma Negri were the proprietors for many years from the late 50s to the late 60s. “My paternal grandparents ran it before that. I remember seeing my auntie Brenda on the evening TV news in 1963, crossing Wigmore Street, with a tray of tea and biscuits: they were for Christine Keeler and John Profumo when they had just been arrested… We only opened at lunchtimes and it was run by my dad’s twin sisters, Anna and Maria. I think they were as big a draw as the steak and kidney puddings.” (Peter Negri)

The Lucky Spot [14 North Audley St W1]

Oddly grand carved stone exterior. Heavy on crypto-Swiss ambience. High-backed carved pews, lots of dark panelling which the owner insists is meant to be Elizabethan pastiche.

Sandwich Bar [Brooks Mews W1] RIP

Hidden gem, utterly overlooked in a superb lost mews by Claridges. Amazing sign and door handle. Brilliant green leatherette seats. Worn Formica tables. Interesting mix of clientele: cabbies & Claridges doormen. Functional and friendly. A model of British utility. (One of only two remaining establishments to be listed in ‘The Good Cuppa Guide’ of the 1960s.)

Chalet Coffee Lounge [81 Grosvenor St W1]

One of the original first generation Coffee bars. This swish little place is kitted out in 60s Swiss-style (very much like the Lucky Spot in North Audley St, St Moritz in Wardour St, and the Tiroler Hut in Westbourne Grove.) This styling was once all the rage as Alpine-exotica briefly irrupted throughout Europe after the war. Wistful seemingly hand-drawn exterior sign, lots of polished brown wood, fancy ironwork lighting, inlaid coloured lights, and pew-bench seating. (Don’t miss the two basement sections hidden at the back.)

RIP/Site of… Rendez-Vous [56 Maddox St W1]

Gaze longingly at the outside Espresso Bongo-like sign and then scoot into one of the very best London caffs left standing around Bond Street. It’s arranged like a domestic living room: covered tables, wooden chairs, lovely lights, lashings of warm Formica…

RIP/Site of… Euro Snack Bar [Swallow St W1]

The little Euro Snack Bar was installed in an obscure street lined with lap-dancing clubs. Superb orange and green frontage (with top 60s typography), small, comfortable booths, low ceilings, and odd little mini-counters on every table for holding the drab-green salt n’ pepper sets. (These are featured on the cover of the book Classic Cafes.)

Source Cafe [78 Brewer St W1] RIP

Ruined cafe (near New Piccadilly) that has some interesting original 1950s exterior features: marble and Vitrolite stall riser with chrome stall-boards; chrome transom/ventilators. (A well-preserved ‘harvest’ mural is still visible through the windows.)

Cafe Rio [58 Brewer St W1]

Unremarkable modernised cafe, however a historic family archive is displayed on the walls.

The New Piccadilly [8 Denman St W1] RIP

A cathedral amongst caffs – a place of reverence. One of the few populuxe Festival of Britain interiors left in the country. Pink Vitrolite coffee machine. Big plastic horseshoe menu. 50s clock. Wall-to-wall yellow Formica. Rows of shiny dark wood booths. The New Piccadilly menu alone is a collectors-item. “I’ve seen 50 years of change in this place,” says proprietor, Lorenzo Marioni, whose late father, Pietro, founded the joint in 1951. Lorenzo was born in a village in the Apennines, not far from Pisa. His parents moved to London shortly after the Second World War. He followed them in 1949. Within a year he was washing up and peeling the potatoes. The Marionis once owned six cafés but sold the premises, one by one, to the next wave of immigrants. Soho gangster Albert Dines once sat in the New Piccadilly and told the young Lorenzo about his association with Prince Felix Yusupov, one of the conspirators who killed Rasputin and sought refuge in London in 1919. In 1956, the cafe became a meeting point for Hungarian dissidents fleeing the Soviet invasion. (Lorenzo remembers the day when one of their number proudly showed his father a rival’s severed finger, wrapped in a handkerchief.)

Lina Stores [18 Brewer St W1]