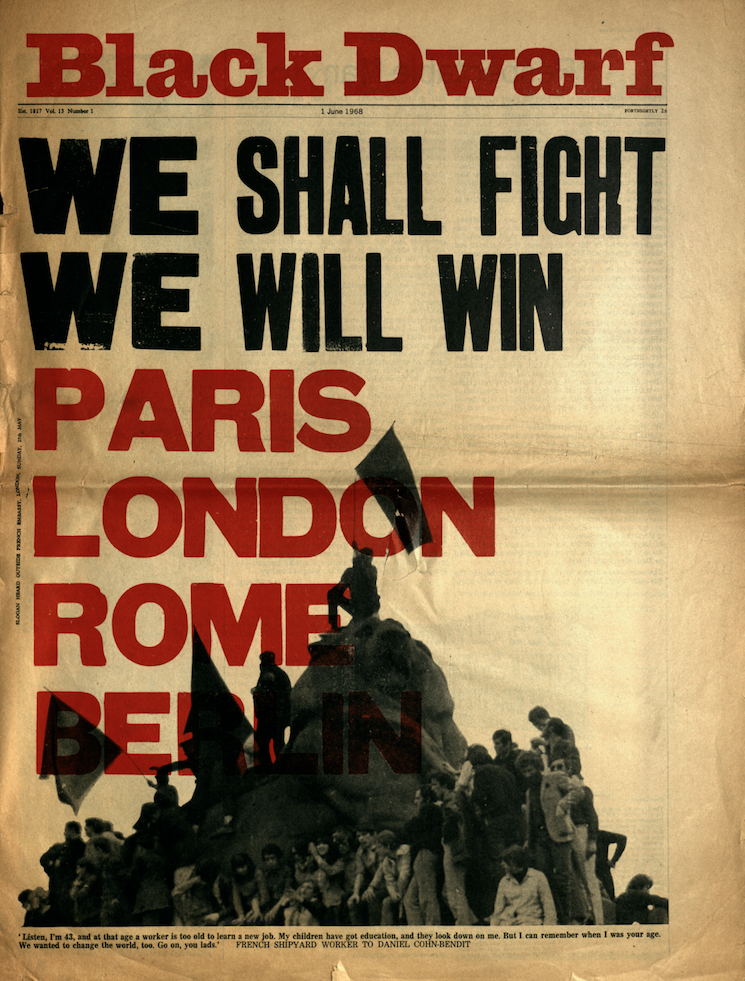

The Revolution of Modern Art and the Modern Art of Revolution

Timothy Clark, Christopher Gray, Donald Nicholson-Smith & Charles Radcliffe & others

(unpublished text,1967)

The Crisis of Modern Art: Dada and Surrealism

‘NEVER BEFORE,’ wrote Artaud, ‘has there been so much talk about civilisation and culture as today, when it is life itself that is disappearing. And there is a strange parallel between the general collapse of life, which underlies every specific symptom of demoralisation, and this obsession with a culture which is designed to domineer over life.’ Modern Art is at a dead end. To be blind to this fact implies a complete ignorance of the most radical theses of the European avant-garde during the revolutionary upheavals of 1910-1925: that art must cease to be a specialised and imaginary transformation of the world and become the real transformation of lived experience itself. Ignorance of this attempt to recreate the nature of creativity itself, and above all its vicissitudes in Dada and Surrealism, has made the whole development of modern art incoherent, chaotic and incomprehensible.

With the Industrial Revolution, there began a change in the whole definition of art – slowly, often unconscioulsy, it changed from a celebration of society and its ideologies to a project of total subversion. From being the focus and guarantee of myth, “great” art became an explosion at the centre of the mythic constellation. Out of mythic time and space it produced a radical historical consciousness which released and reassembled the real contradictions of bourgeois “civilisation.”

Even the antique became subversive – in 50 years, art escaped from the certainties of Augustan values and created its own revolutionary myth of a primitive society. For David and Ledoux, the imperative was to capture the forms of life and self-consciousness which had produced the culture of the ancient world; to recreate rather than to imitate. The 19th century was only to give that proposal a more demoniac and Dionysian gloss.

The project of art – for Blake, for Nietzsche – became the transvaluation of all values and the destruction of all that prevents it. Art became negation: in Goya, in Beethoven, or in Gericault, one can see the change from celebrant to subversive within the space of a lifetime. But a change in the definition of art demanded a change in its forms and the 19th century was marked by an accelerating and desperate attempt at improvising new forms of artistic attack. Courbet began by touting his pictures round the countryside in a marquee and ended in the Commune by superintending the destruction of the Vendome column (the century’s most radical artistic art, which its author immediately disowned).

After the Commune, artists suffered a collective loss of nerve. Mythic time was reborn out of the womb of historical continuity, but it was the mythic time of an isolated and finally obliterated individuality. In the novel, Tolstoy or Conrad struggled to retain a sense of nothingness; irony teetered over into despair; time stopped and insanity took over.

For the Symbolists, the evasion of history became a principle; they gave up the struggle for new revolutionary forms in favor of a purely mythic cult of the isolated artistic gesture. If it was impossible to paint the proletariat, it was equally impossible to paint anything else. So art had to be about nothing; life must exist for art’s sake; the ugly and intolerable truth, said Mallarme with complete disdain, is the “popular form of beauty.” The Symbolists lived on in a realm of an infinitely elegant but stifling tautology. In Mallarme himself, the inescapable subject of poetry is the death of being and the birth of abstract consciousness: a consciousness at once multiform, perfect, magnificently anti-dialectical and radically impotent.

In the end, for all its fury (and Symbolists and Anarchists worked side-by-side in the 1890s) revolutionary art was caught in contradictions. It could not or would not break free of the forms of bourgeois culture as a whole. Its content and method could become transformations of the world, but, while art remained imprisoned within the social spectacle, its transformations remained imaginary. Rather than enter into direct social conflict with the reality it criticized, it transferred the whole problem into an abstract and inoffensive sphere where it functioned objectively as a force consolidating all it wanted to destroy. Revolt against reality became the evasion of reality. Marx’s original critique of the genesis of religious myth and ideology applies word-for-word to the rebellion of bourgeois art: it too “is at the same time the expression of real distress and the protest against real distress. It is the sigh of the oppresses creature, the heart of a heartless world, just as it is the spirit of a spiritless situation. It is the opium of the people” [Marx, Contribution to the critique of Hegel‘s “Philosophy of Right”].

The separation and hostility between the “world” of art and the “world” of everyday life finally exploded in Dada. “Life and art are One,” proclaimed Tzara; “the modern artist does not paint, he creates directly.” But this upsurge of real, direct creativity had its own contradictions. All the real creative possibilities of the time were dependent on the free use of its real productive forces, on the free use of its technology, from which the Dadaists, like everyone else, were excluded. Only the possibility of total revolution could have liberated Dada. Without it, Dada was condemned to vandalism and, ultimately, to nihilism – unable to get past the stage of denouncing an alienated culture and the self-sacrificial forms of expression which it imposed on its artists and their audience alike. It painted pictures on the Mona Lisa, instead of raising the Louvre. Dada flared up and burnt out as an art sabotaging art in the name of reality and reality in the name of art. A tour de force of nihilistic gaiety. The variety, exuberance and audacity of the ludic creativity it liberated, vital enough to transmute the most banal object or event into something vivid and unforeseen, only discovered its real orientation in the revolutionary turmoil of Germany at the end of the First World War. In Berlin, where its expression was most coherent, Dada offered a brief glimpse of a new praxis beyond both art and politics: the revolution of everyday life.

Surrealism was initially an attempt to forge a positive movement out of the devastation left in the wake of Dada. The original Surrealist group understood clearly enough, at least during its heyday, that social repression is coherent and is repeated on every level of experience and that the essential meaning of revolution could only be the liberation and immediate gratification of everyone’s repressed will to live “” the liberation of a subjectivity seething with revolt and spontaneous creativity, with sovereign re-inventions of the world in terms of subjective desire, whose existence Freud had revealed to them (but whose repression and sublimation Freud, as a specialist accepting the permanence of bourgeois society as a whole, could only believe to be irrevocable). They saw quite rightly that the most vital role a revolutionary avant-garde could play was to create a coherent group experimenting with a new lifestyle, drawing on new techniques, which were simultaneously self-expressive and socially disruptive, of extending the perimeters of lived experience. Art was a series of free experiments in the construction of a new libertarian order.

But their gradual lapse into traditional forms of expression – the self-same forms whose pretensions to immortality the Dadaists had already sent up, mercilessly, once and for all – proved to be their downfall: their acceptance of a fundamentally reformist position and their integration within the spectacle. They tried to introduce the subjective dimension of revolution into the communist movement at the very moment when its Stalinist hierarchy had been perfected. They tried to use conventional artistic forms at the very moment when the disintegration of the spectacle, for which they themselves were partly responsible, had turned the most scandalous gestures of spectacular revolt into eminently marketable commodities. As all the real revolutionary possibilities of the period were wiped out, suffocated by bureaucratic reformism or murdered by the firing squad, the Surrealist attempt to supersede art and politics in a completely new type of revolutionary self-expression steadily degenerated into a travesty of its original elements: the mostly celestial art and the most abject communism.

The Transformation of Poverty and the Transformation of the Revolutionary Project

FROM THEN till now . . . nothing. For nearly half a century, art has repeated itself, each repetition feebler, more inane than the last. Only today, with the first signs of a more highly evolved revolt within a more highly developed capitalism, can the radical project of modern art be taken up again and taken up more coherently. It is not enough for art to seek its realisation in practice; practice must also seek its art. The bourgeois artists, rebelling against the mediocrity of mere survival, which was all their class could guarantee, were always tragically at cross-purposes with the traditional revolutionary movement. While the artists – from Keats to the Marx Brothers – were trying to invent the richest possible experience of an absent life the working class – at least on the level of their official theory and organisation – were struggling for the very survival the artists rejected. Only now, with the Welfare State, with the gradual accession of the whole proletariat to hitherto ‘bourgeois’ standards of comfort and leisure, can the two movements converge and lose their traditional animosity. As, in mechanical succession, the problems of material survival are solved and as life, in an equally mechanical succession, becomes more and more disgusting, all revolt becomes essentially a revolt against the quality of experience. One knows very few people dying of hunger. But everyone one knows is dying of boredom.

By now it has become painfully evident to everyone – apart from a gaga radical left – that it is not one or another isolated aspect of contemporary civilisation that is horrifying, but our own lives as a whole, as they are lived on an everyday level. The utter debacle of the left today lies in its failure to notice, let alone understand, the transformation of poverty which is the basic characteristic of life in the highly industrialised countries. Poverty is still conceived in terms of the 19th century proletariat – its brutal struggle to survive in the teeth of exposure, starvation and disease – rather than in terms of the inability to live, the lethargy, the boredom, the isolation, the anguish and the sense of complete meaninglessness which are eating like a cancer through its 20th century counterpart. The left blithely accepts all the mystifications of spectacular consumption. They cannot see that consumption is no more than the corollary of modern production – functioning as both its economic stabilisation and its ideological justification – and that the one sector is just as alienated as the other. They cannot see that all the pseudo variety of leisure masks a single experience: the reduction of everyone to the role of passive and isolated spectators, forced to surrender their own individual desires and to accept a purely fictitious and mass-produced surrogate. Within this perspective, the left has become no more than the avant-garde of the permanent reformism to which neo-capitalism is condemned. Revolution, on the contrary, demands a total change, and today this can only mean to supersede the present system of work and leisure en bloc.

The revolutionary project, as dreamed among the dark satanic mills of consumer society, can only be the creation of a new lease of life as a whole and the subordination of the productive forces to this end. Life must become the game desire plays with itself. But the rediscovery and the realisation of human desires is impossible without a critique of the phantastic form in which these desires have always found the illusory realisation which allowed their real repression to continue. Today this means that ‘art’ – phantasy erected into a systematic culture – has become Public Enemy Number One. It also means that the traditional philistinism of the left is no longer just an incidental embarrassment. It has become deadly. From now on, the possibility of a new revolutionary critique of society depends on the possibility of a sex revolutionary critique of culture and vice versa. There is no question of subordinating art to politics or politics to art. The question is of superseding both of them insofar as they are separated forms.

No project, however phantastic, can any longer be dismissed as ‘Utopian’. The power of industrial productivity has grown immeasurably faster than any of the 19th century revolutionaries foresaw. The speed at which automation is being developed and applied heralds the possibility of the complete abolition of forced labor – the absolute pre-condition of real human emancipation – and, at the same time, the creation of a new, purely ludic type of free activity, whose achievement demands a critique of the alienation of ‘free’ creativity in the work of art. Art must be short-circuited. The whole accumulated power of the productive forces must be put directly at the service of man’s imagination and will to live. At the service of the countless dreams, desires and half-formed projects which are our common obsession and our essence, and which we all mutely surrender in exchange for one or another worthless substitute. Our wildest fantasies are the richest elements of our reality. They must be given real, not abstract powers. Dynamite, feudal castles, jungles, liquor, helicopters, laboratories . . . everything and more must pass into their service. “The world has long haboured the dream of something. Today if it merely becomes conscious of it, it can possess it really.” (Marx, Letter to Ruge, September 1843)

The Realisation of Art and the Permanent Revolution of Everyday Life

“The goal of the Situationists is immediate participation in a varied and passionate life, through moments which are both transient and consciously controlled. The value of these moments can only lie in their real effect. The Situationists see cultural activity, from the point of view of the totality, as a method of experimental construction of everyday life, which can be developed indefinitely with the extension of leisure and the disappearance of the division of labour (and, first and foremost, the artistic division of labour). Art can stop being an interpretation of sensations and become an immediate creation of more highly evolved sensations. The problem is how to produce ourselves, and not the things which enslave us.” (‘Theses on Cultural Revolution’, Internationale Situationniste No. 1, 1958)

IT IS NOT enough to burn the museums. They must also be sacked. Past creativity must be freed from the forms into which it has been ossified and brought back to life. Everything of value in art has always cried aloud to be made real and to be lived. This ‘subversion’ of traditional art is, obviously, merely part of the whole art of subversion we must master (cf. Ten Days That Shook the University). Creativity, since Dada, has not been a matter of producing anything more but of learning to use what has already been produced.

Contemporary research into the factors ‘conditioning’ human life poses implicitly the question of man’s integral determination of his own nature. If the results of this research are brought together and synthesized under the aegis of the cyberneticians, then man will be condemned to a New Ice Age. A recent ‘Commission on the Year 2000’ is already gleefully discussing the possibilities of ‘programmed dreams and human liberation for medical purposes.’ (Newsweek, 16/10/67). If, on the contrary, these ‘means of conditioning’ are seized by the revolutionary masses, then creativity will have found its real tools: the possibilities of everyone freely shaping their own experience will become literally demiurgic. From now on, Utopia is not only an eminently practical project, it is a vitally necessary one.

The construction of situations is the creation of real time and space, and the widest integrated field before it lies in the form of the city. The city expresses, concretely, the prevailing organisation of everyday life. The nightmare of the contemporary megalopolis – space and time engineered to isolate, exhaust and abstract us – has driven the lesson home to everybody, and its very pitilessness has begun to engender a new utopian consciousness. “If man is formed by circumstances, then these circumstances must be formed by man.” (Marx, The Holy Family). If all the factors conditioning us are co-ordinated and unified by the structure of the city, then the question of mastering our own experience becomes one of mastering the conditioning inherent in the city and revolutionising its use. This is the context within which man can begin, experimentally, to create the circumstances that create him: to create his own immediate experience. These “fields of lived experience” will supersede the antagonism between town and country which has dominated human life up to now. They will be environments which transform individual and group experience, and are themselves transformed as a result; they will be cities whose structure affords, concretely, the means of access to every possible experience, and, simultaneously, every possible experience of these means of access. Dynamically inter-related and evolving wholes. Game-cities. In this context, Fourier’s dictum that “the equilibrium of the passions depends upon the constant confrontation of opposites” should be understood as an architectural principle. (The subversion of past culture as a whole finds its focus in the cities. So many neglected themes “” the labyrinth, for example “” remain to be explored.) What does Utopia mean today? To create the real time and space within which all our desires can be realised and all of our reality desired. To create the total work of art.

Unitary urbanism is a critique, not a doctrine, of cities. It is the living critique of cities by their inhabitants: the permanent qualitative transformation, made by everyone, of social space and time. Thus, rather than say that Utopia is the total work of art, it would be more accurate to say that Utopia is the richest and most complex domain serving total creativity. This also means that any specific propositions we can make today are of purely critical value. On an immediate practical level, experimentation with a new positive distribution of space and time cannot be dissociated from the general problems of organisation and tactics confronting us. Clearly a whole urban guerilla will have to be invented. We must learn to subvert existing cities, to grasp all the possible and the least expected uses of time and space they contain. Conditioning must be thrown in reverse. It can only be out of these experiments, out of the whole development of the revolutionary movement, that a real revolutionary urbanism can grow. On a rudimentary level, the blazing ghettoes of the USA already convey something of the primitive splendor, hazardousness and poetry of the environments demanded by the new proletariat. Detroit in flames was a purely Utopian affirmation. A city burnt to make a negro holiday . . . shadows of most terrible, yet great and glorious things to come. . . .

The Work of Art: A Spectacular Commodity

UNFORTUNATELY, it is not only the avant-garde of revolutionary art and politics which has a different conception of the role to be played by artistic creativity. “The problem is to get the artist onto the workshop floor among other research workers, rather than outside industry producing sculptures,” remarks the Committee of the Art Placement Group, which is sponsored by, amongst others, the Tate Gallery, the Institute of Directors, and the Institute of Contemporary Arts (Evening Standard, 1/2/67). In fact, industrialisation of ‘art’ is already a fait accompli. The irreversible expansion of the modern economy has been forcing it to accord an increasingly important position for a long time now. Already the substance of the tertiary sector of the economy – the one expanding the most rapidly – is almost exclusively ‘cultural.’ Alienated society, by revealing its perfect compatibility with the work of art and its growing dependence upon it, has betrayed the alienation of art in the harshest and least flattering light possible. Art, like the rest of the spectacle, is no more than the organisation of everyday life in a form where its true nature can at most be dismissed and turned into the appearance of its opposite: where exclusion can be made to seem participation, where one-way transmission can be made to seem communication, where loss of reality can be made to seem realisation.

Most of the crap passed off as culture today is no more than dismembered fragments – reproduced mechanically without the slightest concern for their original significance – of the debris left by the collapse of every world culture. This rubbish can be marketed simply as historico-aesthetic bric-a-brac or, alternatively, various past styles and attitudes can be amalgamated, up-dated and plastered indiscriminately over an increasingly wide range of products as haphazard and auto-destructive fashions. But the importance of art in the spectacle today cannot be reduced to the mere fact that it offers a relatively unexploited accumulation of commodities. Marshall McLuhan remarks: “Our technology is, also, ahead of its time, if we reckon by the ability to recognise it for what it is. To prevent undue wreckage in society, the artist tends now to move from the ivory tower to the control tower of society. Just as higher education is no longer a frill or a luxury, but a stark need for production in the shaping and structure created by electric technology.” And Galbraith, even more clearly, speaks about the great need “to subordinate economic to aesthetic goals.” (Guardian, 22/2/67).

Art has a specific role to play in the spectacle. Production, once it is no longer answering any real needs at all, can only justify itself in purely aesthetic terms. The work of art – the completely gratuitous product with a purely formal coherence – provides the strongest ideology of pure contemplation possible today. As such it is the model commodity. A life which has no sense apart from contemplation of its own suspension in a void finds its expression in the gadget: a permanently superannuated product whose only interest lies in its abstract technico-aesthetic ingenuity and whose only use lies in the status it confers on those consuming its latest remake. Production as a whole will become increasingly ‘artistic’ insofar as it loses any other raison d’etre.

Rated slightly above the run-of-the-mill consumers of traditional culture is a sort of mass avant-garde of consumers who wouldn’t miss a single episode of the latest ‘revolt’ churned out by the spectacle: the latest solemn 80 minute flick of 360 variegated bare arses, the latest manual of how to freak out without tears, the latest napalm-twisted monsters air-expressed to the local Theatre of Fact. One builds up resistance to the spectacle, and, like any other drug, its continued effectiveness demands increasingly suicidal doses. Today, with everyone all but dead from boredom, the spectacle is essentially a spectacle of revolt. Its function is quite simply to distract attention from the only real revolt: revolt against the spectacle. And, apart from this one point, the more extreme the scandal the better. Any revolt within the spectacular forms, however sincere subjectively – from The Who to Marat/Sade – is absorbed and made to function in exactly the opposite perspective to the one that was intended. A baffled ‘protest vote’ becomes more and more overtly nihilistic. Censorship. Hash. Vietnam. The same old careerism in the same old rackets. Today the standard way of maintaining conformity is by means of illusory revolts against it. The final form taken by the Provos – Saturday night riots protected by the police, put in quarantine, functioning as Europe’s premier avant-garde tourist attraction – illustrates very clearly how resilient the spectacle can be.

Beyond this, there are a number of recent cultural movements which are billed as a coherent development from the bases of modern art – as a contemporary avant-garde – and which are in fact no more than the falsification of the high points of modern art and their integration. Two forms seem to be particularly representative: reformism and nihilism.

The Phoney Avant-Garde

ATTEMPTS TO reform the artistic spectacle, to make it more coherent and, inseparably, to resurrect the illusion of participation in it, are ten a penny. For a time, separated forms – sound, light, jazz, dance, painting, film, poetry, politics, theatre sculpture, architecture, etc – have been brought together, in various juxtapositions, in the mixed and multi-media shows. In kinetic art we are promised the apotheosis of the process. A current Russian group declares: “We propose to exploit all possibilities, all aesthetic and technical means, all physical and chemical phenomena, even all kinds of art as our methods of artistic expression.” (Form, No. 4). The specialist always dreams of ‘broadening his field.’ Likewise the obsessive attempts to make the ‘audience’ ‘participate.’ No one cares to point out that these two concepts are blatantly contradictory, that every artistic form, like every other prevailing social form, is explicitly designed to prohibit even the intervention, let alone the control, of the vast majority of people. Endless examples could be cited. Last winter saw “Vietnamese Free Elections” billed as an experiment in creating “total involvement” in the Vietnamese situation through a fusion of political and dramatic form, etc. “Actors are not wanted,” it was stated. “This is a new exercise in audience participation” that came with the ticket. “If you want to speak, hold up your hand. When you are recognised by the chairman, you must give your real name and the fictional occupation entered on your background sheet. . . . during the course of the meeting, you are operating as a fictional character and not as a spokesman for your personally held beliefs.” (emphasis in original). The Happening is the general matrix of participation art – and the Happening is where it becomes obvious that nothing ever happens. Everyone has lost themselves as totally as they have lost everyone else. Without the drugs, it could be explosive.

Cop art, cop artists. The whole lot moves towards a fusion of forms in a total environmental spectacle complete with various forms of prefabricated and controlled participation. It is just an integral part of the all-encompassing reforming of modern capitalism. Behind it looms the whole weight of a society trying to obscure the increasingly transparent exclusion and repression it imposes on everyone, to restore some semblance of colour, variety and meaning to leisure and work, to “organise participation in something in which it is impossible to participate.” As such, these artists should be treated the same way as police-state psychiatrists, cyberneticians, and contemporary architects. Small wonder their avant-garde cultural ‘events’ are so heavily policed.

Anything art can do, life can do better. A journalist describes the sense of complete reality of driving a static racing car in an ambiance consisting solely of a colour film, which responded to every touch of the steering and acceleration as though he were really speeding round a race track. Even the sensations of a 120 mph smash could be simulated (Daily Express, 18/1/66). Expo ’67, the Holy City of science fiction, boasts a three-million-buck ‘Gyrotron’ designed “to lift its passengers into a facsimile of outer space and then dunk them in a fiery volcano. . . . We orbit up an invisible track. Glowing around us are spinning planets, comets, galaxies . . . man-made satellites, Telstars, moon rockets . . . vooming in our cars are electronic undulations, deep beeps and astral snores.” Finally, the ‘participants’ are plunged down a “red incinerator, surrounded by simulated lava, steam and demonic shrieks” (Life, 15/5/67). Reinforced by the sort of conditioning made possible by the discoveries of the kinetic artists, such techniques could ensure an unprecedented measure of control. Sutavision, an abstract form of colour TV, already mass-marketed, offers to provide “wonderful relaxation possibilities” giving “a wide series of phantasies” and functioning as “part of a normal home or business office.” “Radiant colours moving in an almost hypnotic rhythm across the screen . . . wherein one can see any number of intriguing spectacles.” Box three, a further refinement of TV, can manipulate basic mood changes through the rhythms and the frequency of the light patterns employed (Observer Magazine, 23/10/66). Still more sinister is the combination of total kinetic environments and a stiff dose of acid. “We try to vaporise the mind,” says a psychedelic artist, “by bombing the senses…” The Us Company [a commune of painters, poets, film-makers, teachers and weavers that lived and worked together in an abandoned church in Garneville, New York, USA] artists call their congenial wrap-around a “be-in” because the spectator is to exist in the show, rather than look at it. The audience becomes disorientated from their normal time sense and preoccupations. . . . The spectator feels he is being transported to mystical heights.” And this “is invading not only museums and colleges, but cultural festivals, discotheques, movie houses and fashion shows” (Life, 3/10/66). To date, Leary is the only person to have attempted to pull all this together. Having reduced everyone to a state of hyper-impressionable plasticity, he incorporated a backwoods myth of the modern-scientific-truth-underlying-all-world-religions, a cretin’s catechism broadcast persuasively at the same time as it was expressed by the integral manipulation of sense data. Leary’s personal vulgarity should not blind anyone to the possibilities implicit in this. A crass manipulation of subjective experience accepted ecstatically as a mystical revelation.

“All this art is finished. . . . Squares on the wall. Shapes on the floor. Emptiness. Empty rooms” (Warhol to a reporter from Vogue). Nihilism is the second most widespread form of contemporary ‘avant-garde’ culture; the morass stretches from playwrights like Ionesco and film-makers like Antonioni, through novelists like Robbe-Grillet and Burroughs, to the paintings and sculpture of the pop, destructive and auto-destructive artists. All re-enact a Dadaist revulsion from contemporary life “” but their revolt, such as it is, is purely passive., theatrical and aesthetic, shorn of any of the passionate fury, horror or desperation which would lead to a really destructive praxis. Neo-Dada, whatever its formal similarities to Dada, is re-animated by a spirit diametrically opposed to that of the original Dadaist groups. “The only truly disgusting things,” said Picabia, “are Art and Anti-Art. Wherever Art rears its head, life disappears.” Neo-Dada, far from being a terrified outcry at the almost complete disappearance of life, is, on the contrary, an attempt to confer a purely aesthetic value on its absence and on the schizophrenic incoherence of its surrogates. It invites us to contemplate the wreckage, ruin and confusion surrounding us, and not to take up arms in the gaiety of the world’s subversion, pillage and total overthrow. Their culture of the absurd reveals only the absurdity of their culture.

Purely contemplative nihilism is no more the special province of artists than is modern reformism. In fact, neo-Dada lags way behind the misadventures of the commodity-economy itself – every aspect of life today could pass as its own parody. The Naked Lunch pales before any of the mass media. Its real significance is quite different. For pop art is not only, as Black Mask remarks, the apotheosis of capitalist reality: it is the last ditch attempt to shore up the decomposition of the spectacle. Decay has reached the point where it must be made attractive in its own right. If nothing has any value, then nothing must become valuable. The bluff may be desperate but no one dares to call it, here or anywhere else. And so Marvel comics become as venerable as Pope. The function of neo-Dada is to provide an aesthetic and ideological alibi for the coming period, to which modern commerce is condemned, of increasingly pointless and self-destructive products: the consumption/anti-consumption of the life/anti-life. Galbraith’s subordination of economic to aesthetic goals is perfectly summed up in the Mystic Box. “Throw switch ‘on.’ Box rumbles and quivers. Lid slowly rises, a hand emerges and pushes switch off. Hand disappears as lid slams shut. Does absolutely nothing but switch off!” The nihilism of modern art is merely an introduction to the art of modern nihilism.

The Intelligentsia Split in Two

THESE TWO movements – the attempt to reform the spectacle and the attempt to arrest its crisis as purely contemplative nihilism – are distinct but in no way contradictory manoeuvres. In both cases, the function of the artist is merely to give aesthetic consecration to what has already taken place. His job is purely ideological. The role played today by the work of art has dissociated everything in art which awoke real creativity and revolt from everything which imposed passivity and conformism. Its revolutionary and its alienated elements have sprung apart and become the living denial of one another. Art as commodity has become the arch-enemy of all real creativity. The resolution of the ambiguity of culture is also the resolution of the ambiguity of the intelligentsia. The present cultural set-up is potentially split into two bitterly opposed factions. The majority of the intelligentsia has, quite crudely, sold out. At the same time, its truly dissident and imaginative elements have refused all collaboration, all productivity, within the forms tolerated by social power and are tending more and more to become indistinguishable from the rest of the new lumpenproletariat in their open contempt and derision for the ‘values’ of consumer society. While the way of life of the servile intelligentsia is the living denial of anything remotely resembling either creativity or intelligence, the rebel intelligentsia is becoming caught up in the reality of disaffection and revolt, refusing to work and inevitably faced, point blank, with a radical reappraisal of the relationship between creativity and everyday life. Frequenting the lumpen, they will learn to use other weapons than their imagination. One of our first moves must be to envenom the latent hostility between these two factions. It shouldn’t be too difficult. The demoralisation of the servile intelligentsia is already proverbial. The contradictions between fake glamour and the reality of their mental celebrity are too flagrant to pass unperceived, even by those who are, indisputably, the most stupid people in contemporary society.

Revolt, the Spectacle and the Game

THE REAL creativity of the times is at the antipodes of anything officially acknowledged to be ‘art.’ Art has become an integral part of contemporary society and a ‘new’ art can only exist as a supersession of contemporary society as a whole. It can only exist as the creation of new forms of activity. As such, it [‘new’ art] has formed an integral part of every eruption of real revolt over the last decade. All have expressed the same furious and baffled will to live, to live every possible experience to the full – which, in the context of a society which suppresses life in all its forms, can only mean to construct experience and to construct it against the given order. To create immediate experience as purely hedonistic and experimental enjoyment of itself can be expressed by only one social form – the game – and it is the desire to play that all real revolt has asserted against the uniform passivity of this society of survival and the spectacle. The game is the spontaneous way everyday life enriches and develops itself; the game is the conscious form of the supersession of spectacular art and politics. It is participation, communication and self-realisation resurrected in their adequate form. It is the means and the end of total revolution.

The reduction of all lived experience to the production and consumption of commodities is the hidden system by which all revolt is engendered, and the tide rising in all the highly industrialised countries can only throw itself more and more violently against the commodity-form. Moreover, this confirmation can only become increasingly embittered as the integration effected by power is revealed as more and more clearly to be the re-conversion of revolt into a spectacular commodity (q.v., the transparence of the conforming non-conformity dished up for modern youth). Life is revealed as a war between the commodity and the ludic. As a pitiless game. And there are only two ways to subordinate the commodity to the desire to play: either by destroying it, or by subverting it.

The Real Avant-Garde: The Game-Revolt of Delinquency, Petty Crime and the New Lumpen

THE JUVENILE delinquents – not the pop artists – are the true inheritors of Dada. Instinctively grasping their exclusion from the whole of social life, they have denounced its products, ridiculed, degraded and destroyed them. A smashed telephone, a burnt car, a terrorised cripple are the living denial of the ‘values’ in the name of which life is eliminated. Delinquent violence is a spontaneous overthrow of the abstract and contemplative role imposed on everyone, but the delinquents’ inability to grasp any possibility of really changing things once and for all forces them, like the Dadaists, to remain purely nihilistic. They can neither understand nor find a coherent form for the direct participation in the reality they have discovered, for the intoxication and sense of purpose they feel, for the revolutionary values they embody. The Stockholm riots, the Hell’s Angels, the riots of Mods and Rockers “” all are the assertion of the desire to play in a situation where it is totally impossible. All reveal quite clearly the relationship between pure destructivity and the desire to play: the destruction of the game can only be avenged by destruction. Destructivity is the only passionate use to which one can put everything that remains irremediably separated. It is the only game the nihilist can play; the bloodbath of the 120 Days of Sodom proletarianised along with the rest.

The vast escalation of petty crime “” spontaneous, everyday crime on a mass level – marks a qualitatively new stage in contemporary class conflict: the turning point between pure destruction of the commodity and the stage of its subversion. Shoplifting, for example, beyond being a grass-roots refusal of hierarchically organised distribution, is also a spontaneous rebuttal of the use of both product and productive force. The sociologists and floorwalkers concerned – neither group being noted for a particularly ludic attitude towards life – have failed to spot either that people enjoy the act of stealing, or, through an even darker piece of dialectical foul-play, that people are beginning to steal because they enjoy it. Theft is, in fact, a summary overthrow of the whole structure of the spectacle; it is the subordination of the inanimate object, from whose free use we are withheld, to the living sensations it can awake when played with imaginatively within a specific situation. And the modesty of something as small as shoplifting is deceptive. A teenage girl interviewed recently remarked: “I often get this fancy that the world stands still for an hour and I go into a shop and get rigged” (Evening Standard, 16/8/66). Alive, in embryo, is our whole concept of subversion: the bestowal of a whole new use value on this useless world and against this useless world, subordinated to the sovereign pleasure of subjective creativity.

The formation of the new lumpen prefigures several features of an all-encompassing subversion. On the one hand, the lumpen is the sphere of complete social breakdown of apathy, negativity and nihilism – but, at the same time, in so far as it defines itself by its refusal to work and its attempt to use its clandestine leisure in the invention of new types of free activity, [the lumpen] is fumbling, however clumsily, with the quick of the revolutionary supersession now possible. As such it could quickly become social dynamite. It only needs to realise the possibility of everyday life being transformed, objectively, for its last illusions to lose their power, e.g., the futile attempt to revitalize immediate experience subjectively, by heightening its perception with drugs, etc. The Provo movement in 1966 was the first groping attempt of this new, and still partly heterogeneous, social force to organise itself into a mass movement aimed at the qualitative transformation of everyday life. At its highest moment, [the Provo movement]’s upsurge of disruptive self-expression superseded both traditional art and traditional politics. It collapsed not through any essential irrelevance of the social forces it represented, but through their complete lack of any real political consciousness: through their blindness to their own hierarchical organisation and through their failure to grasp the full extent of the crisis of contemporary society and the staggering libertarian possibilities it conceals.

Initially, the new lumpen will probably be our most important theatre of operations. We must enter it as a power against it and precipitate its crisis. Ultimately, this can only mean to start a real movement between the lumpen and the rest of the proletariat: their conjunction will define the revolution. In terms of the lumpen itself, the first thing to do is to dissociate the rank-and-file from the incredible crock of shit raised up, like a monstrance, by their leaders and ideologists. The false intelligentsia – from the CIA-subsidised torpor of the latest New Left, to the sanctimonious little tits of International Times – are a New Establishment whose tenure depends on the success with which they can confront the most way-out point of social and intellectual revolt. The parody they stage can only arouse a growing radicalism and fury on the part of those they claim to represent. The Los Angeles Free Press, distilling their experience of revolt in an article aptly entitled To Survive in the Streets, could in all seriousness conclude: “Summing up: Dress warm, keep clean and healthy, eat a balanced diet, live indoors and avoid crime. Living in the streets can be fun if you conscientiously study the rules of the game.” (Reprinted in The East Village Other, 15/6/67). Hippie racketeers should certainly steer clear of public places, come the day. The poesie faite par tous has been known to be somewhat trigger-happy in the past.

Revolution as a Game

THE NEW revolutionary movement can be no more than the organisation of popular revolt into its most coherent, its richest form. And there is no organisation to date which would not completely betray it. All previous political critiques of the repressive hierarchy engendered by the past revolutionary argument – that of Solidarity, for example – have completely missed the point: they were not focused on precisely what it was that this hierarchy repressed and perverted in the form of passive militancy. In the context of the radical ‘ethics’ still bogged down in singularly distasteful forms of sub-Christian masochism, the ludic aspects of the revolution cannot be over-emphasised. Revolution is essentially a game and one plays it for the pleasure involved. Its dynamic is a subjective fury to live, not altruism. It is totally opposed to any form of self-sacrificial subordination of oneself to a cause – to Progress, to the Proletariat, to Other People. Any such attitude is diametrically opposed to the revolutionary appreciation of reality: it is no more than an ideological extension of religion for the use by the ‘revolutionary’ leaderships in justifying their own power and in repressing every sign of popular creativity.

The game is the destruction of the sacred – whether it be the sanctity of Jesus or the santity of the electric mixer and the Wonderloaf. Tragedy, said Lukacs, is a game played in the sight of godlessness. The true form of godlessness will be the final achievement of revolution – the end of the illusory and all its forms, the beginning of real life and its direct self-consciousness.

The revolutionary movement must be a game as much as the society it prefigures. Ends and means cannot be disassociated. We are concerned first and foremost with the construction of our own lives. Today, this can only mean the total destruction of power. Thus the crucial revolutionary problem is the creation of a praxis in which self-expression and social disruption are one and the same thing: of creating a style of self-realisation which can only spell the destruction of everything which blocks total realisation. From another point of view, this is the problem of creating the coherent social form of what is initially and remains essentially an individual and subjective revolt. Only Marx’s original project, the creation of the total man, of an individual reappropriating the entire experience of the species, can supersede the individual vs. Society dualism by which hierarchical power holds itself together while it holds us apart. If it fails in this, then the new revolutionary movement will merely build an even more labyrinthine illusory community; or, alternatively, it will shatter into an isolated and ultimately self-destructive search for kicks. If it succeeds, then it will permeate society as a game that everyone can play. There is nothing left today that can withstand a coherent opposition once it has established itself as such. Life and revolution will be invented together or not at all.

All the creativity of the time will grow from this movement and it is in this perspective that our own experiments will be made and should be understood. The end of this process will not merely be the long overdue end of this mad, disintegrating civilisation. It will be the end of pre-history itself. Man stands on the verge of the greatest breakthrough ever made in the human appropriation of nature. Man is the world of man and a new civilisation can only be based on man’s free and experimental creation of his own world and his own creation. This creation will no longer accept any internal division or separation. Life will be the creation of life itself. The total man will be confronted only with his ever-increasing appropriation of nature, of his own nature, finally elaborated, in all of its beauty and terror, as our ‘worthy opponent’ in a ludic conflict where everything is possible.