Pace Gallery has mounted a world class mini-museum show on the art of the Happening using its vast holdings as well as supplemental gleanings loaned from the Whitney, MOMA and Getty museums.

Pace Gallery has mounted a world class mini-museum show on the art of the Happening using its vast holdings as well as supplemental gleanings loaned from the Whitney, MOMA and Getty museums.

Category Archives: New York

Overloaded: The Story Of White Light/White Heat | MOJO

“NO ONE LISTENED TO IT. BUT THERE IT IS, FOREVER – THE QUINTESSENCE OF ARTICULATED PUNK. AND NO ONE GOES NEAR IT.”– Lou Reed, August, 2013

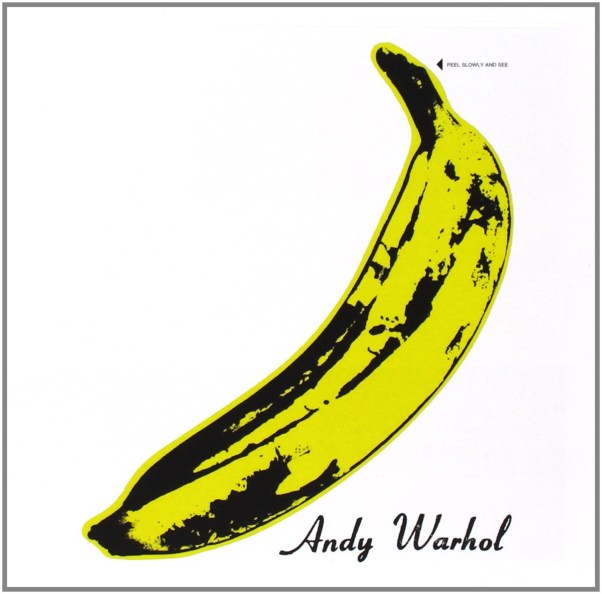

BY MID-1967, ONLY a few months after The Velvet Underground’s debut album was released, their iconic ice queen singer Nico was a solo artist, and pop art svengali Andy Warhol was no longer managing and feeding the group. Warhol’s parting gift: the all-black cover idea for their follow-up – the album they would name White Light/White Heat. Meanwhile, the band scrabbled to survive in the drug-soaked art-scene demi-monde of Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

“Our lives were chaos,” VU guitarist Sterling Morrison told me in 1994. “Things were insane, day in and day out: the people we knew, the excesses of all sorts. For a long time, we were living in various places, afraid of the police. At the height of my musical career, I had no permanent address.”

There were mounting internal tensions, too, over direction and control between Lou Reed and John Cale, the group’s founders, especially after their debut album’s failure to launch. “White Light/White Heat was definitely the raucous end of what we did,” Morrison affirmed. But, he insisted, “We were all pulling in the same direction. We may have been dragging each other off a cliff, but we were definitely all going in the same direction.”

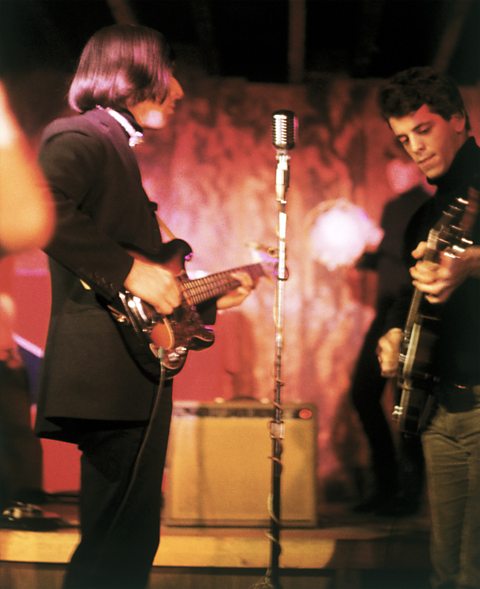

From that turbulence and frustration, Reed, Cale, Morrison and drummer Moe Tucker created their second straight classic. Where The Velvet Underground And Nico was a demonstration of breadth and vision, developed in near-invisibility even before the band met Warhol – “We rehearsed for a year for that album, without doing anything else,” Cale claims – White Light/White Heat was a more compact whiplash: the exhilarating guitar violence starting with the title track, peaking in Reed’s atonal-flamethrower solo in I Heard Her Call My Name; the experimental sung and spoken noir of Lady Godiva’s Operation and The Gift; the propulsive, distorted eternity of sexual candour and twilight drug life, rendered dry and real in Reed’s lethal monotone, in Sister Ray.

“By this time, we were a touring band,” Cale explains. “And the sound we could get on stage – we wanted to get that on the record. In some performances, Moe would go up first, start a backbeat, then I would come out and put a drone on the keyboard. Sterling would start playing, then Lou would come out, maybe turn into a Southern preacher at the mike. That idea of us coming out one after the other, doing whatever we wanted, that individualism – it’s there on Sister Ray, in spades.”

White Light/White Heat was also the Velvets’ truest record, the most direct, uncompromised document of their deep, personal connections to New York’s avant-garde in the mid-’60s; the raw, independent cinema of Jack Smith, Jonas Mekas and Piero Heliczer; Cale’s pre-Velvets experiences in drone, improvisation and radical composition with John Cage and the early minimalists La Monte Young and Tony Conrad; Reed’s dual immersion, from his days at Syracuse University, in the free jazz of Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor and the metropolitan-underworld literature of William Burroughs and Hubert Selby, Jr.

“I’m in there with a B.A. in English – I’m no naif,” Reed told me shortly before his death. “And being in with that crowd, the improvisers, the film-makers, of course it would affect where I was going. We said it a hundred times; people thought we were being arrogant and conceited. We’re reading those authors, watching those Jack Smith movies. What did you think we were going to come out with?”

“WE WERE ALL PULLING IN THE SAME DIRECTION. WE MAY HAVE BEEN DRAGGING EACH OTHER OFF A CLIFF…”– Sterling Morrison

The Players

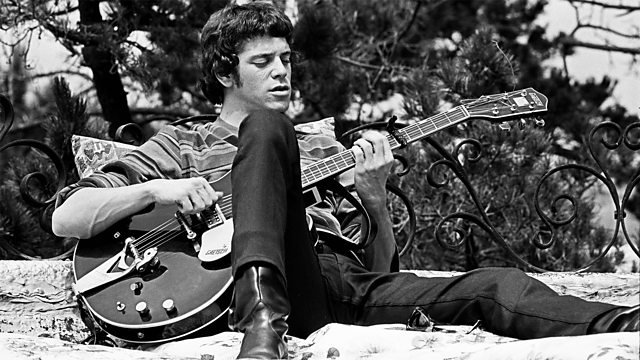

LOU REED

1942-2013. Guitarist/vocalist and primary songwriter. “No one censured it,” he said of WL/WH. “Because no one listened to it.”

JOHN CALE

Bass guitar/viola/keyboards. The classically trained Welshman provided the deadpan monologue for The Gift: “Everyone was hellbent on being heard.”

STERLING MORRISON

1942-1995. Guitar and “medical sound effects” on Lady Godiva’s Operation: “Maybe our frustrations led the way.”

MOE TUCKER

Drums. Provider of the group’s relentless, unfussy propulsion. “The songs were the songs,” she drily notes.

ANDY WARHOL

1928-1987. Pop art icon, art-director and manager of The Velvet Underground. Parted ways with the group in the run-in to White Light/White Heat.

TOM WILSON

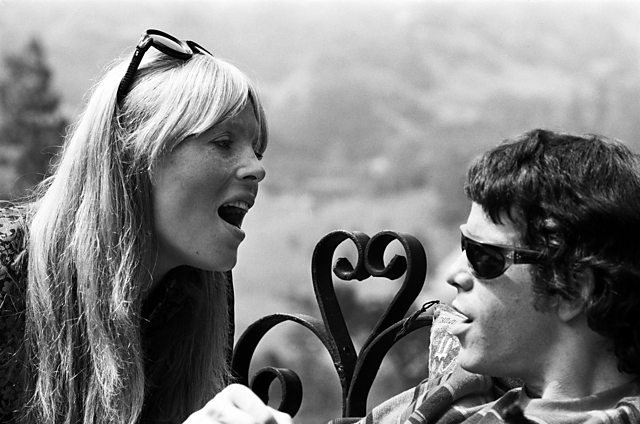

1931-1978. WL/WH producer and babe magnet. Notable track record with Dylan, Zappa, Simon & Garfunkel, the VU and Nico (pictured).

HUBERT SELBY JR.

1928-2004. Novelist/poet of the New York demi-monde. Inspired Sister Ray: “It’s a taste of Selby, uptown,” said Reed.

ORNETTE COLEMAN

Saxophonist/composer, architect of free jazz. His lines influenced Reed’s splintering lead guitar approach on I Heard Her Call My Name.

CECIL TAYLOR

Jazz pianist and poet admired by Lou Reed. His experimental approach fed into WL/WH. Tom Wilson produced his 1956 album, Jazz Advance.

Players Photos: Getty / Rex

II.

In September 1967 at Mayfair Studios – located on Seventh Avenue near Times Square and the only eight-track operation in town – The Velvet Underground put White Light/White Heat to tape. “I think it was five days,” Cale once told me.

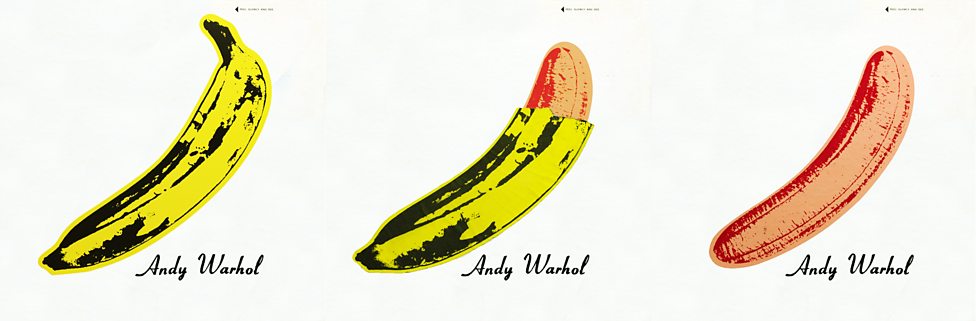

Gary Kellgren, Mayfair’s house engineer, previously worked with the Velvets on part of the debut ‘Banana’ album and engineered the spring-’67 recording of Nico’s solo debut, Chelsea Girl. The producer, officially, was Tom Wilson, also with a track record with the group. In 1965, when the producer was still at Columbia, he invited Reed and Cale to play for him in his office. “We dragged Lou’s guitar, my viola and one amplifier up there,” said Cale. “We played Black Angel’s Death Song for him. He knew there was energy and potential.” At Mayfair, Cale mostly remembered Wilson’s “parade of beautiful girls, coming through all the time. He had an incredible style with women.”

But the Velvets’ volume and aggression posed problems for the recording men, and Reed insisted that Kellgren simply walked out during Sister Ray. “At one point, he turns to us and says, ‘You do this. When you’re done, call me.’ Which wasn’t far from the record company’s attitude. Everything we did – it came out. No one censured it. Because no one listened to it.”

On Sister Ray, Reed sang live across the feral seesawing of the guitars, drums and Cale’s Vox organ as each pressed for dominance in the mix. “It was competition,” Cale says. “Everyone was hellbent on being heard.” The ending, though, was easy. “We just knew when it was over,” Morrison remembered. “It felt like ending. And it did.”

There was a real Sister Ray: “This black queen,” Reed says. “John and I were uptown, out on the street, and up comes this person – very nice, but flaming.” Reed wrote the words, a set of incidents and character studies, on a train ride from Connecticut after a bad Velvets show there. “It was a propos of nothing. ‘Duck and Sally inside’ – it’s a taste of Selby, uptown. And the music was just a jam we had been working on” – provisionally titled Searchin’, after one of the lyrics (“I’m searchin’ for my mainline”).

“The lyrics aren’t negative,” Reed argues. “White Light/White Heat – it has to do with methamphetamine. Sister Ray is all about that. But they are telling you stories – and feelings. They are not stupid. And the rhythm is interesting. But you’d think that. I studied long enough.”

White Light/White Heat is renowned for its distortion and unforgiving thrust. But it also features the simple, airy yearning of Here She Comes Now, one of the Velvets’ finest ballads. And there are telling, human details even in the noise, like the breakdown at the end of White Light/White Heat, when Cale’s frantic, repetitive bass playing leaps forward in an out-of-time spasm. “I’m pretty sure it broke down,” he says of his part, “because my hand was falling off.”

Lady Godiva’s Operation was, Cale explains, “a radio-theatre piece, trying to use the studio to create this panorama of a story” – lust, transfiguration and ominously vague surgery that goes fatally wrong. The Gift was just the band and Cale’s rich Welsh intonation. Reed wrote the story – an examination of nerd-ish obsession peppered with wily minutiae (the Clarence Darrow Post Office) and ending in sudden death – at Syracuse University, for a creative writing class. Reed: “The idea was two things going at once” – Cale in one stereo channel, music in the other. “If you got tired of the words, you could just listen to the instrumental.”

Cale’s reading was a first take. The sound of the blade plunging through the cardboard, “right through the centre of Waldo Jeffers’ head,” was Reed stabbing a canteloupe with a knife. Frank Zappa, also working at Mayfair with The Mothers Of Invention, was there. “He said, ‘You’ll get a better sound if you do it this way,’” Reed recalled. “And then he says, ‘You know, I’m really surprised how much I like your album,’” referring to the ‘Banana’ LP. “Surprised? OK.” Reed smiled. “He was being friendly.”

Wayne McGuire’s ecstatic review of White Light/White Heat, in a 1968 issue of rock magazine Crawdaddy, cited Reed’s playing in “I Heard Her Call My Name” as “the most advanced lead guitar work I think you’re going to hear for at least a year or two.” McGuire also noted the jazz in there, comparing the album – especially Sister Ray – to recordings by Cecil Taylor and the saxophonists John Coltrane and Albert Ayler. “Sister Ray is much like [Coltrane’s] Impressions,” McGuire wrote, “in that it is a sustained exercise in emotional stampede and modal in the deepest sense: mode as spiritual motif, mode as infinite musical universe.”

It was rare understanding for the time. A brief review in the February 24, 1968 edition of Billboard was more measured: “Although the words tend to be drowned out by pulsating instrumentation, those not minding to cuddle up to the speakers will joy [sic] to narrative songs such as The Gift, the story of a boy and girl.” Still, the trade bible promised, “Dealers who cater to the underground market will find this disk a hot seller.”

“THERE WAS CLOSE COMPETITION WITH BOB DYLAN. HE WAS GETTING INTO PEOPLE’S HEADS. WE THOUGHT WE COULD DO THAT.”– John Cale

III.

That didn’t happen. There was a single, the title track coupled with Here She Comes Now. It didn’t help. By the fall of 1968, Cale was gone. Forced to leave the group he co-founded, the Welshman embarked on a second career as a producer, composer and solo artist that continues to this day.

The Velvets went back on the road, and soon into the studio, with a new bassist, Doug Yule. They found a new power in quiet and more decorative pop on their next two albums, until Reed left in 1970 to begin, eventually, his own extraordinary solo life. Live, without Cale, the Velvets still played Sister Ray.

This new Deluxe collection includes Cale’s last studio sessions with The Velvet Underground. Temptation Inside Your Heart and Stephanie Says were recorded in New York in February, 1968, produced by the band for a prospective single (according to Cale and Morrison). Temptation was their idea of a Motown dance party, with congas and comic asides caught by accident as Reed, Cale and Morrison overdubbed their male-Marvelettes harmony vocals. Stephanie Says was the first of Reed’s portrait songs, named after women in crisis and overheard conversation (Candy Says, Lisa Says, Caroline Says I and II). Cale’s viola hovered through the arrangement like another singer: graceful and comforting.

On a spare day in May, 1968, between shows in Los Angeles and San Francisco, the Velvets returned to L.A.’s T.T.G. Studios – where they had worked on The Velvet Underground And Nico – and taped two versions of another viola feature, Hey Mr. Rain. In a 1994 interview, Cale described the song’s droning melancholy and rhythmic suspense as “trying to have a pressure cooker. That’s what those songs were about – Sister Ray, European Son [on The Velvet Underground And Nico], Hey Mr. Rain. They were things we could exploit on stage, flesh out and improvise. But we were driving it into the ground. We hadn’t spent any time quietly puttering around the way we did before the first album.”

The classic quartet cut another song at T.T.G., a recently unearthed attempt at Reed’s Beginning To See The Light. The song, briskly redone with Yule, would open Side Two of the Velvets’ third album. This take has a vintage kick – Martha & The Vandellas’ Dancing In The Street taken at the gait of I’m Waiting For The Man. You also hear the impending change. “Here comes two of you/Which one would you choose?,” Reed sings, an intimation of the cleaving that would alter the Velvets for good.

“John has said we didn’t get to finish what we started – that is sadly true,” Reed acknowledged. “However, as far as we got, that was monumental.” White Light/White Heat, everything leading to it and gathered here – “I would match it,” he says, “with anything by anybody, anywhere, ever. No group in the world can touch what we did.”

Back in 1994, I asked Moe Tucker about the fuzz and chaos of White Light/White Heat – how much they reflected the daily trials and tensions of being The Velvet Underground, always first and alone in their ideals and attack. She replied with her usual, common sense: “I don’t know if I go along with that. The songs were the songs, and the way we played them was the way we each wanted to play them.”

Anything else, she declared with a grin, was “a little too philosophical.”

“THAT WAS MONUMENTAL. I WOULD MATCH IT WITH ANYTHING BY ANYBODY, ANYWHERE, EVER. NO GROUP IN THE WORLD CAN TOUCH WHAT WE DID.”– Lou Reed

Brushstrokes series – Roy Lichtenstein (1965-66)

Brushstrokes (1965) was the first element of the Brushstrokes series.

Brushstrokes (1965) was the first element of the Brushstrokes series.

“Brushstrokes series is the name for a series of paintings produced in 1965–66 by Roy Lichtenstein. It also refers to derivative sculptural representations of these paintings that were first made in the 1980s. In the series, the theme is art as a subject, but rather than reproduce masterpieces as he had starting in 1962, Lichtenstein depicted the gestural expressions of the painting brushstroke itself. The works in this series are linked to those produced by artists who use the gestural painting style of abstract expressionism made famous by Jackson Pollock, but differ from them due to their mechanically produced appearance. The series is considered a satire or parody of gestural painting by both Lichtenstein and his critics. After 1966, Lichtenstein incorporated this series into later motifs and themes of his work. In the early 1960s, Lichtenstein reproduced…

View original post 236 more words

Kenny Wilson at Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution 12th July 2017

This is a video of my talk at BRLSI in July. It’s not great quality but you get the whole thing! I originally put it on YouTube but it got blocked because of my use of two Bob Dylan songs. This was a bit disappointing but I have decided to upload it here instead. I hope Bob won’t mind too much, he always seemed to understand the true value of copyright theft and plagiarism!

Me? I’m having trouble with the Tombstone Blues!

Velvet Underground & Nico: John Cale’s Track Commentary

John Cale offers his memories of recording each song on the iconic Velvet Underground debut

John Cale offers his memories of recording each song on the iconic Velvet Underground debut

Source: Velvet Underground & Nico: John Cale’s Track Commentary

Everyone’s heard the famous maxim, generally accredited to legendary music producer Brian Eno: while the Velvet Underground’s debut, The Velvet Underground & Nico, sold a paltry 30,000 copies upon release in 1967, every person who bought one of those 30,000 copies started a band. Though a slight exaggeration, the line is a testament to the album’s far-reaching influence trumping its commercial failure. Lou Reed, John Cale, Sterling Morrison, and Maureen Tucker merged raw rock and roll with musique concrète and the avant-garde to create an untamed and menacing sound that perfectly underscored their poetic tales of drug deals, sadomasochistic sex and other snapshots of the urban underworld.

Emboldened by manager and patron Andy Warhol—who linked them up with featured vocalist, Nico—the Velvet Underground’s brand of leather-clad Lower East Side cool emerged onto vinyl with all of its grit and daring intact, serving as a beacon to generations of young artists unwilling to conform to pop music niceties. Decades ahead of its time, it planted the seeds for punk, glam, goth, and a host of others genres to flourish.

In honor of the groundbreaking album’s 50th anniversary this month, Cale spoke to PEOPLE about his memories recording The Velvet Underground & Nico. Read on for his exclusive track by track commentary.

“Sunday Morning”

“That happened one Sunday morning at Lou’s friend’s house. We were out boozing and running around the Lower East Side and Lou suddenly had a great idea. He said, ‘Hey, I’ve got a friend who lives around the corner, let’s go see him.’ And it was like three o’clock [in the morning]. I said, ‘Yeah, ok!’ We ran over, and he had a harmonium in the corner of his living room. Generally what we did when we went anywhere, we just zeroed in on the instruments and started playing. It was kind of manic—anywhere you’d go, if you saw an instrument you’d just pick it up and start playing. Lou saw the guitar, I saw the harmonium, and off we went writing ‘Sunday Morning.’

“I’m Waiting for the Man”

“I remember the first gigs we did with just him and me —I had a recorder and a viola, and he had an acoustic guitar. We’d go sit on the sidewalk outside the Baby Grand [bar] up in Harlem on 125th and see if we could make some money. Every time we got moved on the cop always had a suggestion of where we should go. ‘Try 75th on Broadway! That’s a good spot.’ So we’d go down there and make a little bit more money.”

“Femme Fatale”

“Andy saw that Lou was moping around the factory, and he gave him a list of words. He said, ‘Here are 14 words, go write songs with these words.’ And Lou was never happier. He had a task in hand and he sat down. That was a lot of fun for him. We had our own thing going [before Warhol] but he showed up and was more of a guy helping us not forget who we were. He would always say things like, ‘Tell Lou, don’t forget to put little swear words in that song.’ He was reminding us of who we really were. And he didn’t have to say very much to do that, he could just be around and it would be like that because he’d notice what was going on around you. He’d notice the art that was going on. We didn’t understand it. We were just flabbergasted by it, but we loved it at the same time.”

“Venus in Furs”

“Lou wrote ‘Venus in Furs’ while we were playing around when we met at Pickwick. He told me that the label wouldn’t let him record all of the songs he really wanted to do. That sort of pissed me off. I asked him what they were and he showed them to me. He’d play them on acoustic guitar and I said, ‘These are rock songs. These can be really big and orchestral if you want them to be.’ Then I said, ‘Let’s just do it ourselves, let’s get our own label and get our own recording situation—not here.’ So we put a band together. That was a signature number for us.”

“Run Run Run”

“’Run Run Run’ was always the first number to do, because it was up-tempo and got everybody going. It was great.”

“All Tomorrow’s Parties”

“We had made the arrangement for ‘All Tomorrow’s Parties’ before Nico came along. That was the result of a year of weekend work—sitting around on the weekend and just playing and playing and playing and playing until you slowly gradually moved out of the folk music side of things.

The record was all done with just us playing, there were no effects involved in that. We tried a version where Nico doubles her vocal, but the vocal just became too heavy. “But the noise of putting paper clips in between the strings of the piano gave it a ring that made it a little more orchestral. We were trying to make orchestral stuff. We were trying to be Phil Spector, really. Phil Spector would mix Wagnerian orchestrations with R&B. That was a really unique combination. We had the drone. The viola wasn’t wasn’t used, so the piano became the drone. Whenever we’d try to do something, we’d always try to find something that would be the drone.”

“Heroin”

“’Heroin’ is really special. At that point it was kind of a resident of the band because it was so important to the set. Everybody had heard of it. It was one of the attractions of the set, apart from the attitude of the band. Whatever we were doing, we were trying to get more people in the door. But we had a lot of different ideas of how to do that. My idea of getting people in the door was doing something experimental. I tried to get Lou to see that we don’t have to do the same set every night. That was a direct result of all these club owners in New York saying, ‘You’ve got to play one or two songs that are in the top 10, otherwise you won’t get a gig.’ We said, ‘We’re not doing that. We’ve got our own numbers.’ And until Andy showed up we barely got any venues at all. I thought, ‘One selling point that we can have is that we never do the same set twice.’ We improvised songs every night, which was rather fun with Lou. I said, ‘We can give Dylan a run for his money if we just improvise every night, because our lyrics are just as good.’”

“There She Goes Again”

“That was probably the easiest one, with a soul riff from Marvin Gaye. You could hear Lou’s time at Pickwick writing pop songs.”

“I’ll Be Your Mirror”

“Lou was writing songs for Nico, and some of the best songs he’d written were written for her. That was one of them. She was becoming more interested at that time in being her own songwriter. She’d sit down and write poetry, and to her it was in a foreign language. She was trying to find poetic language in a foreign language, because she was German-speaking. But she was determined, she bought a harmonium for herself and was really single-minded about doing all that.”

“The Black Angel’s Death Song“

“’Black Angel Death Song’ no one ever got. It would go over everybody’s head. But in general, I think what people responded to, even if they didn’t understand it, was the energy that we had. Lou and I, we knew we could play these songs, but we were never genuflecting to each other about how to play them. The performances were more done as a bald statement of fact: ‘This is what we do. Whether you like it or not, we don’t care.’ And we didn’t care whether we played it well. We really were on top of that. And we were excited about what we were doing. And then the band gets a record deal right away? Come on, that’s great. Really exciting.”

“European Son”

“’European Son’ in my mind was purely for improvisation. Whenever we played anywhere, we couldn’t wait to get to the point where we’d improvise and do ‘European Son.’ It was always different. That was the fun part for us, doing those improvisations. And those improvisations would really get the best of us in the end, because they’d go on and on and on and on. We’d be up there for an hour just improvising before we’d even done a song! In San Diego we did that. That’s kind of the rep we had when we got to San Francisco and L.A.

Bill Graham didn’t appreciate all the songs and improvisations that were going on. He thought we were invading [the San Francisco group’s] territory. There wasn’t much love lost between us and the West Coast. Lou was always talking about, ‘Never mind the flower children, give us the hard drugs!’ We were happy that Woodstock ended up in the mud—that kind of resentment was very healthy, I thought.”

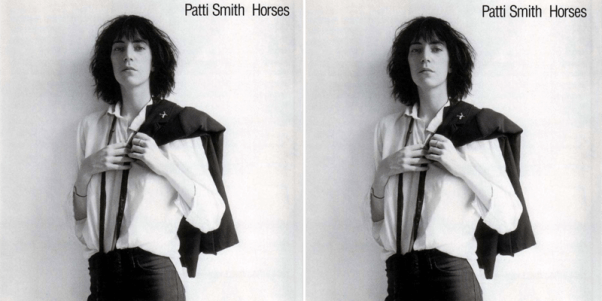

Camille Paglia on the Iconic Cover of Patti Smith’s Horses | Literary Hub

Source: Camille Paglia on the Iconic Cover of Patti Smith’s Horses | Literary Hub

“THE MAPPLETHORPE PHOTO SYNTHESIZES MY PASSIONS AND WORLD-VIEW”

In 1975, Arista Records released Horses, the first rock album by New York bohemian poet Patti Smith. The stark cover photo, taken by someone named Robert Mapplethorpe, was devastatingly original. It was the most electrifying image I had ever seen of a woman of my generation. Now, two decades later, I think that it ranks in art history among a half-dozen supreme images of modern woman since the French Revolution.

I was then teaching at my first job in Vermont and turning my Yale doctoral dissertation, Sexual Personae, into a book. The Horses album cover immediately went up on my living-room wall, as if it were a holy icon. Mapplethorpe’s portrait of Patti Smith symbolized for me not only women’s new liberation but the fusion of high art and popular culture that I was searching for in my own work.

From its rebirth in the late 1960s, the organized women’s movement had been overwhelmingly hostile to rock music, which it called sexist. Patti Smith’s sudden national debut galvanized me with the hope (later proved futile) that hard rock, the revolutionary voice of the counterculture, would also be endorsed by feminism.

Smith herself emerged not from the women’s movement but from the artistic avant-garde as well as the decadent sexual underground, into which her friend and lover Mapplethorpe would plunge ever more deeply after their breakup.

Unlike many feminists, the bisexual Smith did not base her rebellion on a wholesale rejection of men. As an artist, she paid due homage to major male progenitors; she wasn’t interested in neglected foremothers or a second-rate female canon. In Mapplethorpe’s half-transvestite picture, she invokes her primary influences, from Charles Baudelaire and Frank Sinatra to Bob Dylan and Keith Richards, the tormented genius of the Rolling Stones who was her idol and mine.

Before Patti Smith, women in rock had presented themselves in conventional formulas of folk singer, blues shouter, or motorcycle chick. As this photo shows, Smith’s persona was brand new. She was the first to claim both vision and authority, in the dangerously Dionysian style of another poet, Jim Morrison, lead singer of the Doors. Furthermore, in the competitive field of album-cover design inaugurated in 1964 with Meet the Beatles(the musicians’ dramatically shaded faces are recalled here), no female rocker had ever dominated an image in this aggressive, uncompromising way.

The Mapplethorpe photo synthesizes my passions and world-view. Shot in steely high contrast against an icy white wall, it unites austere European art films with the glamorous, ever-maligned high-fashion magazines. Rumpled, tattered, unkempt, hirsute, Smith defies the rules of femininity. Soulful, haggard and emaciated yet raffish, swaggering and seductive, she is mad saint, ephebe, dandy and troubadour, a complex woman alone and outward bound for culture war.

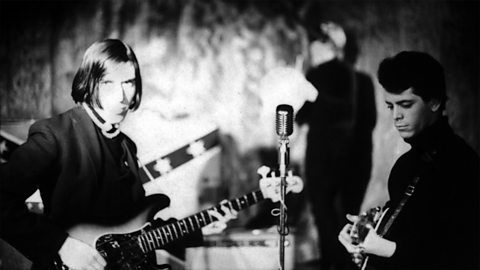

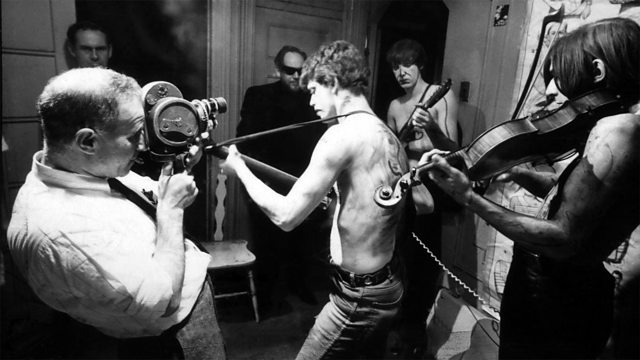

Adam Ritchie: Photographer

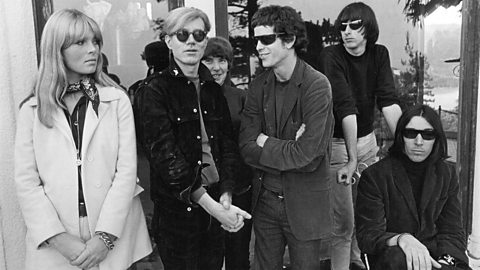

I came across Adam Ritchie when I was researching into the Velvet Underground. Most of the early pictures of the band were taken by him and Lisa Law. It seems strange that there are not more pictures of the band from this time when you consider the number of photos taken at Andy Warhol’s Factory by Billy Name and various others. The quality of Richie’s pictures are brilliant, especially as he had no training as a photographer (mind you, neither did Billy Name who also produced some outstanding prints).

His pictures of the Velvet’s first gigs at Cafe Bizarre in New York are fascinating as are the only pictures I have seen of the New York Society for Clinical Psychiatry annual dinner at the Delmonico Hotel, New York, 13 January 1966. This still seems like one of the oddest events ever staged. What did the guests think whilst Gerard Malanga wielded his whip and the band churned out distortion and feedback at maximum volume? I’d have loved to have been a fly on the wall! The fact that it was a psychiatrist’s convention makes it even more surreal.

His photographs of Pink Floyd and Syd Barrett at the UFO club in London in 1966 also give a real insight into the period. Both the Floyd and Andy Warhol were experimenting with light shows at the time.

This is from his web site:

I went from London to New York in 1962. Found a loft on Bond Street just off the Bowery and got work doing international economic research. I moved to 277 East 10th Street in the East Village. In 1964 I bought a 35mm camera and became a photographer instead. I worked for Conde Nast’s Mademoiselle and Glamour, Esquire, Look, ESP Disk, etc. I was always interested in alternative culture and jazz. Working at night at the Bleeker Street Cinema, I got to know Jonas Mekas, Barbara Rubin, Betsey Johnson Cecil Taylor, Sunny Murray and some of the Fugs.

I disliked Andy Warhol’s celebration of tinsel and superficial glamour until I found myself on the 27th floor of an advertising agency showing my pictures to an art director. One of Andy’s helium filled silver pillows floated very slowly in a straight, even line across the huge window behind him. I was spellbound with amazement. It seemed impossible for steady movement and a lack of gusting outside the window at the 27th floor level. I didn’t say anything about it to the art director but it was clear that Andy’s understanding of the time was profound. Barbara Rubin introduced me to the Velvet Underground before she introduced them to Andy Warhol. I was mad about them because of their music and how they felt serious about what they were doing.

I came back to London in 1966 and immediately went to John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins and Joe Boyd’s new UFO Club. I took photos of Pink Floyd’s earliest performances at the club and at the Round House. I taught photography at Central School of Art as well until 1973 when I started building houses for people in Wales and later in London until 1995.

While I was building houses, my photo lab closed down suddenly. All my photos and negatives were destroyed without my knowledge. Later I just happened to discover a battered old paper carrier bag with the Velvet Underground and Pink Floyd photos in it. That, apart from a few prints, was all that was left of 10 years professional photography.

I had always kept in touch with Rudy Franchi from the Bleeker Street Cinema. In 1997 he offered me my first exhibition, called “The Lost Photographs” at his gallery in Boston. Since then they have appeared in 40 or more books and hundreds of magazines and newspapers. They have been in exhibitions at the Whitney Museum and Boo-Hooray Gallery in New York, Victoria & Albert Museum, Tate Liverpool, Idea Gallery and Artisan Gallery in London, in Paris, Bologna, Vienna, Tokyo and in Sweden and Australia. There will be many of my photos in a new Velvet Underground show at the Cité de la Musique opening between March and August 2016.

Some of the Velvet Underground photos are also in the Andy Warhol Museum collection.

Since then it has been cabinet making, teaching furniture design, local community organising, then running a furniture company for 8 years and now I’m retired, singing in two choirs, growing delicious fruit and vegetables in allotments, Irish set dancing every week and going to classes.

What follows is an interview with Adam Ritchie from ‘Wombat’ photography and arts blog. He seems to have been equally blessed and ill-fated!

Are you a self-taught photographer?

In 1962/63 I was working doing international economic research for a New York company called Business International and living on the Lower East Side. One day I saw a rat walking calmly along my street, East 10th St, between 1st Avenue and Avenue A. I wanted to photograph what I saw. A friend, Larry Fink, was a professional photographer and he helped me buy a 35mm camera one friday, after work. I took my first photographs on Saturday, developed the film in Larry’s darkroom that evening, spent Sunday printing with his help. I went to work early on monday and covered the wall of my office with 20 prints. Everyone came in and looked at the pictures, pretty amazed that it had all happened since the office closed on friday.

The boss suggested that there was such feeling in the photos, that that is what I should really be doing. I said it was just a new hobby I had taken up that weekend for the first time and underneath it all, I was a serious economist. He kept on at me about it until finally, he fired me with three months salary in advance to force me to try and earn a living from photography. I already had a holiday back to England booked and paid for. I planned a series of photographs of people in London. Mademoiselle Magazine bought and published six pages of them. Following that I got published by Glamour Magazine (also Conde Nast), Esquire, Look and others.So yes, I was self taught.

What is your educational background?

Normal, except that I did my last two years of school at the Lycee Français de Londres and then two years of a degree in Economics at Amherst College in Massachusetts on a scholarship.

Why do I take pictures?

I’ve always being interested in seeing things and how you organize what you see. I was involved in the Underground Avant-garde in London and New York, so I wanted to show people what I saw. I saw John Coltrane, Thelonius Monk, Cecil Taylor and Velvet Underground and others in New York and when I went back to London in summer 1966, I photographed Pink Floyd earliest performances.

I taught photography at Central School of Art in London from 1966 to 1973 and took lots of other photographs, but in 1973 I resigned from teaching, went to Wales and built houses for other people. I learned from books and experience. I built houses there for 4 years and then moved back to London still building for another 8 years. I discovered about then that all my photographs and negatives had been destroyed (except for Velvet Underground and Pink Floyd pictures and a few prints. I spent a couple of years at a furniture college learning cabinet making and furniture design and launched my own studio and also taught furniture design.

Were you friends with the Velvet Underground?

I talked a bit with John Cale while I was photographing the making of the Venus in Furs film but mainly I photographed them because I loved their music. My friend, Barbara Rubin, was playing a nun in the Venus in Furs film and phoned me to say I had to come and listen to this amazing new band. Obviously I took cameras. Piero Heliczer, whose film it was, was very informal, sometimes with a film camera, sometimes blowing an alto sax. There was a CBS News film crew doing a story about The Making of an Underground Film as well so the whole thing was like a happening with everything going on at the same time.

What were your influences?

In the early 1960s, I lived in an apartment in London together with 6-7 men and women. We all read William Burroughs (Naked Lunch). He visited our apartment. We read Genet, Kerouac, Flan O’Brian, Dostoievski, Samuel Becket, etc. We listened to Charlie Parker, Coltrane, Miles Davis Thelonius Monk, Bud Powell every night.

I worked in Better Books, the most avant-garde bookshop in London with all the artists and intellectuals constant visitors. We organized happenings and spontaneous demonstrations.

The truth is I was young, intelligent, very interested in culture and alternative underground culture.

I had lived for three years in New York as a child and had later got a scholarship to attend university in Massachusetts1958-60. I had not enjoyed the university in the States but wanted to try again, so I got a work permit and went to New York in 1962 for four years. Although being an economist for work in the day, the rest of the time I listened to and saw Coltrane, Cecil Taylor, Monk. I went to many art galleries. I also worked as assistant Night Manager at the Bleeker Street Cinema and met Barbara Rubin and Jonas Mekas. I went to happenings and jazz and movies every week. I became a photographer in order to photograph what I saw. Back in London in 1966, I started a campaign in my very poor neighborhood for playgrounds and community facilities. I spent three or four years working for that in my free time and it became the largest community scheme of its sort in Europe. It is 115 000 m2 in west London built underneath an elevated motorway called Westway. Later I built houses for ten years and afterwards became a furniture maker/designer.

The Velvet Underground & Nico at 50: A New York Extravaganza in Paris

It is 50 years since The Velvet Underground & Nico album was recorded. A major new exhibition in Paris tells the story of the group which created it and of the New York scene which produced them. Parisians hold the Velvets in particular esteem and, as Allan Campbell notes, the city itself has often been the scene of key moments in the Velvets’ history, not least a legendary appearance at Le Bataclan.

It’s a cold January evening in Paris. Outside Le Bataclan an estimated 2,000 disconsolate rock fans are milling around in front of the ornate Chinese-style theatre on the Boulevard Voltaire. They are ticket-less and unable to gain access to a concert which would later be considered the venue’s most famous; a title only lost on Friday 13 November 2015, when dreadful events unfolded at an Eagles of Death Metal show.

For the first time since the demise of the original Velvet Underground, co-conspirators Lou Reed and John Cale with ‘chanteuse’ Nico were to perform a one-off acoustic set at Le Bataclan for the benefit of French TV show Pop 2 and one thousand grateful fans.

It was 1972; Nico was already a veteran of three solo albums; Cale had made his debut with Vintage Violence, remixed a Barbra Streisand album and cut an LP with minimalist composer Terry Riley, while Reed – surprisingly – was yet to release a solo album.

In fact, on the night of the Paris concert he should have been at the Portobello Hotel in London for a ‘listening party’ for his debut LP, Lou Reed, with no less than Lillian Roxon, then the leading rock critic in the US.

Despite what Melody Maker described as “a minor ‘speed-freak riot’ in the foyer”, the Bataclan concert was a languid, beguiling affair but not quite as languid as the ensuing live album, which had been mastered at the wrong speed.

France’s on-off love affair with US culture was nothing new; notably, réalisateurs Jean Luc Godard and Jean Pierre Melville had already expressed it on screen. But with the Velvets, the relationship seemed to become more geographically specific.

In return for the Statue of Liberty, New York had belatedly returned the favour by sending its dark emissaries to the City of Light. And the French, who had after all defined noir, seemed especially appreciative.

In 1990, when the Velvets reunited – spontaneously, it seemed – once again it would be in Paris. This time it was at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, which had mounted an Andy Warhol multi-media show and invited key members of his Factory crowd to attend.

It was expected that Reed and Cale would play something from their Warhol tribute album, Songs for Drella, but they were soon joined onstage by band mates Sterling Morrison and Mo Tucker.

“We kicked into Heroin, which we hadn’t played in twenty-two years”, said Cale, “And it was just the same as always. After I got off stage … I was on the point of tears”.

As the location for this rapprochement suggests, it seems that Parisians have always viewed the Velvet Underground as a work of art and not just because of their association with Warhol.

Now, with the 50th anniversary of the recording of their debut, The Velvet Underground & Nico, the city has again come good for the Velvets with an extensive celebratory show at the Philharmonie de Paris entitled The Velvet Underground: New York Extravaganza.

Curated by Christian Fevret, founder of Les Inrockuptibles music magazine, with art director and producer Carole Mirabello, the exhibition places the Velvets at the centre of New York’s post war avant garde, probably the only environment which could have produced such a group.

Paris, don’t forget what you taught the rest of us: if you keep an open heart it will beat forever. Goodnight.John Cale

Music and visuals tell the VU story, taking in Reed and Cale’s first meeting in 1964 to their first show with Nico at the annual dinner of the New York Society for Clinical Psychiatry (Hotel Delmonico, New York, 1966), then their appearances at Warhol’s legendary Exploding Plastic Inevitable multimedia show and then on to the group’s eventual disintegration.

Even after all these years, the music and photographs of the Velvets scintillate.

John Cale returned to Paris to open the exhibition, with full band, string quartet and guests including Pete Doherty, Mark Lanegan and Lou Doillon. Cale, in a nod both to the city’s recent pain and its ability to inspire, reportedly concluded the concert with these words:

“Paris, don’t forget what you taught the rest of us: if you keep an open heart it will beat forever. Goodnight.”

The Velvet Underground: New York Extravaganza is at the Philharmonie de Paris until 21 August, 2016.

Story behind the album cover [recordart blog]