Source: ‘The Velvet Underground and Nico’: 10 Things You Didn’t Know – Rolling Stone

Actually, I did know most of this, but not Warhol’s idea of putting a crack on the record to make the phrase ‘I’ll Be Your Mirror’ repeat over and over again. Inspirational, and an idea later used by the Beatles at the end of Sgt. Pepper but not in quite as radical a way. I also didn’t know about the drums breaking down in ‘Heroin’ or Sterling Morrison’s hatred of Frank Zappa. Although I did know about Lou Reed’s hatred of Frank Zappa and also Frank Zappa’s hatred of not only the VU but also The Beatles and The Doors, and pop and rock music in general!

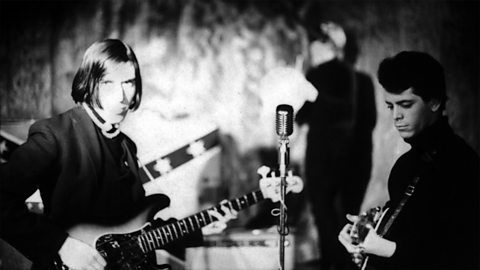

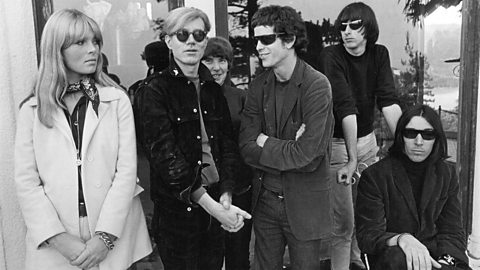

A half-century on, The Velvet Underground and Nico remains the quintessential emblem of a certain brand of countercultural cool. Not the Haight-Ashbury or Sgt. Pepper kind but an eerier, artier, more NYC-rooted strain. Released on March 12th, 1967, the Velvet Underground‘s debut was an album that brought with it an awareness of the new, the possible and the darker edge of humanity. Bolstered by the patronage of Andy Warhol and the exotic vocal contributions of Nico, Lou Reed, John Cale, Sterling Morrison and Maureen Tucker declared their independence from Top 40 decorum with a gritty, innovative and unapologetically self-possessed work. In many ways, The Velvet Underground and Nico was the first rock album that truly seemed to invite the designation alternative.

Fifty years after its release, the LP still sounds stunningly original, providing inspiration and a blueprint for everything from lo-fi punk rock to highbrow avant-garde – and so much in between. Read on for 10 fascinating facts about the album’s creation.

1. Lou Reed first united with John Cale to play a knockoff of “The Twist.”

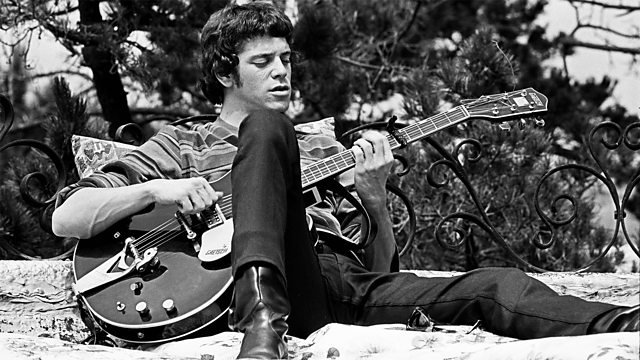

Reed’s professional music career took root in 1964 when he was hired as a staff songwriter at Pickwick Records, an NYC-based budget label specializing in soundalikes of contemporary chart-toppers. “We just churned out songs; that’s all,” Reed remembered in 1972. “Never a hit song. What we were doing was churning out these rip-off albums.”

When ostrich feathers became the hot trend in women’s fashion magazines, Reed was moved to write a parody of the increasingly ridiculous dance songs sweeping the airwaves. “The Twist” had nothing on “The Ostrich,” a hilariously oddball number featuring the unforgettable opening lines: “Put your head on the floor and have somebody step on it!” While composing the song, Reed took the unique approach of tuning all six of his guitar strings to the same note, creating the effect of a vaguely Middle Eastern drone. “This guy at Pickwick had this idea that I appropriated,” he told Mojo in 2005. “It sounded fantastic. And I was kidding around and I wrote a song doing that.”

Reed recorded the song with a group of studio players, releasing the song under the name the Primitives. Despite the unorthodox modes, Pickwick heard potential in “The Ostrich” and released it as a single. It sold in respectable quantities, convincing the label to assemble musicians to pose as the phony band and promote the song at live gigs. Reed began hunting for potential members, valuing attitude as much as musical aptitude. He found both in John Cale.

The pair crossed paths at a house party on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, where Reed was drawn to Cale’s Beatle-y long hair. A classically trained prodigy, the young Welshman had moved to the city months earlier to pursue his musical studies and play viola with avant-garde composer La Monte Young’s Theater of Eternal Music. Intrigued by his pedigree, Reed invited him to join the Primitives. Sensing the opportunity for easy money and some laughs, Cale agreed.

Gathering to rehearse the song, Cale was astonished to discover that the “Ostrich tuning” produced essentially the same drone he was accustomed to playing with Young. Clearly on the same musical wavelength, they connected on a personal level afterwards. “More than anything it was meeting Lou in the coffee shop,” Cale says in a 1998 American Masters documentary. “He made me nice cup of coffee out of the hot water tap, and sat me down and started quizzing me as to what I was really doing in New York. There was a certain meeting of the minds there.”

2. “The Black Angel’s Death Song” got the band fired from their residency.

Sterling Morrison became involved with the duo after a chance meeting with Reed, his classmate at Syracuse University, on the subway. Together they formed a loose band with Cale’s roommate Angus MacLise, a fellow member of the Theater of Eternal Music collective. Lacking a consistent name – they morphed from the Primitives to the Warlocks, and then the Falling Spikes before taking their soon-to-be-iconic final moniker from a pulp paperback exposé – the quartet rehearsed and recorded demos in Cale’s apartment throughout the summer of 1965.

The fledgling Velvet Underground were befriended by pioneering rock journalist Al Aronowitz, who managed to book them a gig at a New Jersey high school that November. This irritated the bohemian MacLise, who resented having to show up anywhere at a specific time. When informed that they would be receiving money for the performance, he quit on the spot, grumbling that the group had sold out. Desperate to fill his spot on the drums, they asked Morrison’s friend Jim Tucker if his sister Maureen (known as “Moe”) was available. She was, and the classic lineup was in place.

School gymnasiums were not the ideal venue for the band. “We were so loud and horrifying to the high school audience that the majority of them – teachers, students and parents – fled screaming,” Cale says in American Masters. Instead, Aronowitz found them a residency in a Greenwich Village club, the Café Bizarre. Its name was something of a misnomer, as neither the owners nor the handful of customers appreciated the way-out sounds. In a half-hearted attempt at assimilation, the group added some rock standards to their repertoire. “We got six nights a week at the Café Bizarre, some ungodly number of sets, 40 minutes on and 20 minutes off,” Morrison described in a 1990 interview. “We played some covers – ‘Little Queenie,’ ‘Bright Lights Big City’ … the black R&B songs Lou and I liked – and as many of our own songs as we had.”

Three weeks in, the tedium became too much bear. “One night we played ‘The Black Angel’s Death Song’ and the owner came up and said, ‘If you play that song one more time you’re fired!’ So we started the next set with it,” Morrison told Sluggo! of their ignoble end as a bar band in a tourist trap. The self-sabotage had the desired effect and they were relieved of their post – but not before they caught the attention of Andy Warhol.

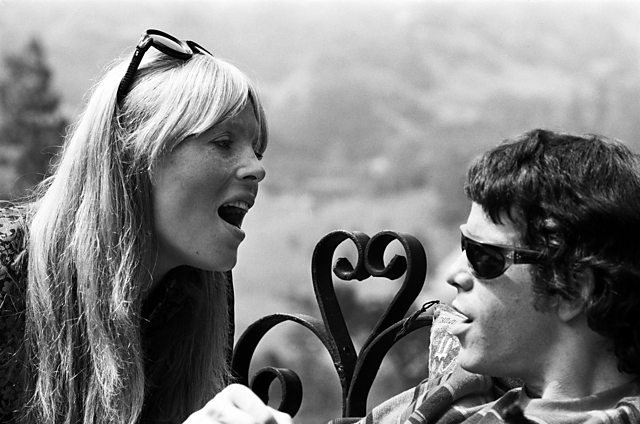

3. The album’s co-producer refused to accept cash payment, asking for a Warhol painting instead.

Already a prolific painter, sculptor and filmmaker, by the mid-Sixties Warhol sought to expand his famous Factory empire into rock & roll. On the advice of confidant Paul Morrissey, the 37-year-old art star dropped in on the Velvet Underground’s set at the Café Bizarre and impulsively extended an offer to act as their manager. The title would have rather loose connotations, though he did make one significant alteration to their sound. Fearing that the group lacked the requisite glamour to become stars, he suggested the addition of a striking German model known as Nico. The proposal was not met with complete enthusiasm – Reed was particularly displeased – but she was tentatively accepted into the ranks as a featured vocalist.

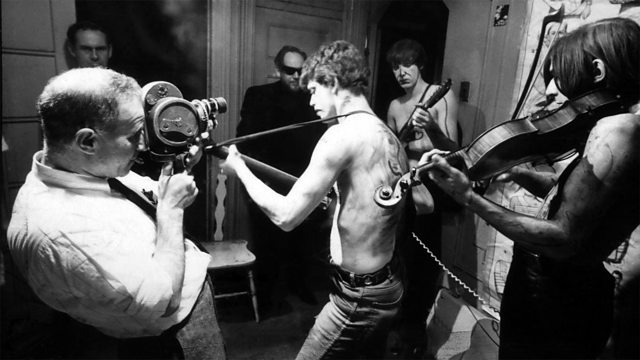

Now billed as the Velvet Underground with Nico, Warhol incorporated the band into a series of multimedia performances dubbed the Exploding Plastic Inevitable: a marriage of underground music, film, dance and lights. Also assisting was 27-year-old Norman Dolph, an account representative at Columbia Records who moonlit as a DJ and soundman. “I operated a mobile discotheque – if not the first then at least the second one in New York,” he later told author Joe Harvard. “I was an art buff, and my thing was I’d provide the music at art galleries, for shows and openings, but I’d ask for a piece of art as payment instead of cash. That’s how I met Andy Warhol.”

By the spring of 1966, Warhol decided it was time to take his charges into the recording studio. Knowing little about such matters, he sought out Dolph for advice. “When Warhol told me he wanted to make a record with those guys, I said, ‘Oh, I can take care of that, no problem. I’ll do it in exchange for a picture,'” he said in Sound on Sound. “I could have said I’d do it in exchange for some kind of finder’s fee, but I asked for some artwork, [and] he was agreeable to that.”

Dolph was tasked with booking a studio, covering a portion of the costs himself, producing and leaning on colleagues at Columbia to ultimately release the product. For his trouble he was given one of Warhol’s silver “Death and Disaster Series” canvases. “A beautiful painting, really. Regrettably, I sold it around ’75, when I was going through a divorce, for $17,000. I remember thinking at the time, ‘Geez, I bet Lou Reed hasn’t made $17,000 from this album yet.’ If I had it today, it would be worth around $2 million.”

4. It was recorded in the same building that later housed Studio 54.

Dolph’s day job at Columbia’s custom labels division saw him working with smaller imprints that lacked their own pressing plants. One of his clients was Scepter Records, best known for releasing singles by the Shirelles and Dionne Warwick. Their modest offices on 254 West 54th Street in midtown Manhattan were noteworthy for having their own self-contained recording facility.

Though the Velvet Underground were studio novices, it didn’t take an engineer to know that the room had seen better days. Reed, in the liner notes to the Peel Slowly and See boxed set, describes it as “somewhere between reconstruction and demolition … the walls were falling over, there were gaping holes in the floor, and carpentry equipment littered the place.” Cale recalls being similarly underwhelmed in his 1999 autobiography. “The building was on the verge of being condemned. We went in there and found that the floorboards were torn up, the walls were out, there was only four mics working.”

It wasn’t glamorous, and at times it was barely functional, but for four days in mid-April 1966 (the exact dates remain disputed), the Specter Records studios would play host to the bulk of the Velvet Underground and Nico recording sessions. Though Warhol played only a distant role in proceedings, he would return to 254 West 54th Street a great deal in the following decade, when the ground floor housed the infamous Studio 54 nightclub.

5. Warhol wanted to put a built-in crack in all copies of the record to disrupt “I’ll Be Your Mirror.”

Andy Warhol is nominally the producer of The Velvet Underground and Nico, but in reality his role was more akin to producer of a film; one who finds the project, raises the capital and hires a crew to bring it to life. On the rare occasions he did attend the sessions, Reed recalls him “sitting behind the board gazing with rapt fascination at all the blinking lights … Of course he didn’t know anything about record production. He just sat there and said, ‘Oooh that’s fantastic.'”

Warhol’s lack of involvement was arguably his greatest gift to the Velvet Underground. “The advantage of having Andy Warhol as a producer was that, because it was Andy Warhol, [engineers] would leave everything in its pure state,” Reed reflected in a 1986 episode of The South Bank Show. “They’d say, ‘Is that alright, Mr. Warhol?’ And he’d say, ‘Oh … yeah!’ So right at the very beginning we experienced what it was like to be in the studio and record things our way and have essentially total freedom.”

Although he didn’t try to specifically shape the band in his own image, Warhol did make some suggestions. One of his more eccentric ideas for the track “I’ll Be Your Mirror,” Reed’s delicate ballad inspired by his simmering romantic feelings towards Nico, never came to fruition. “We would have the record fixed with a built-in crack so it would go, ‘I’ll be your mirror, I’ll be your mirror, I’ll be your mirror,’ so that it would never reject,” Reed explained in Victor Bockris’ Uptight: The Velvet Underground Story. “It would just play and play until you came over and took the arm off.”

6. “There She Goes Again” borrows a riff from a Marvin Gaye song.

Reed’s time at Pickwick instilled in him a fundamental fluency in the language of pop music. Often overshadowed by his innovative instrumental arrangements and taboo lyrical subjects, his ear for an instantly hummable tune is apparent with catchy confections like “Sunday Morning,” the album’s opening track. Bright and breezy, with Reed’s androgynous tone replacing Nico’s planned lead, the song’s introductory bass slide is an intentional nod to the Mamas and the Papas’ “Monday, Monday,” which topped the charts when it was first recorded in April 1966.

“There She Goes Again” also draws from the Top 40 well, borrowing a guitar part from one of Motown’s finest. “The riff is a soul thing, Marvin Gaye’s ‘Hitch Hike,’ with a nod to the Impressions,” Cale admitted to Uncut in 2012. “That was the easiest song of all, which came from Lou’s days writing pop at Pickwick.”

It would earn the distinction of becoming one of the first Velvet Underground tracks to ever be covered – half a world away in Vietnam. A group of U.S. servicemen, performing under the name the Electrical Banana during their off hours, were sent a copy of The Velvet Underground and Nico by a friend who thought they would appreciate the fruit on the cover. They appreciated the music as well, and resolved to record a version of “There She Goes Again.” Unwilling to wait until they returned to the States, they built a makeshift studio in the middle of the jungle by tossing down wooden pallets, pitching a tent, fashioning mic stands from bamboo branches and plugging their amps into a gas generator.

7. The drums break down during the climax of “Heroin.”

The most infamous track on the album is also one of the oldest, dating back to Reed’s days as a student at Syracuse University, where he performed with early folk and rock groups and sampled illicit substances. Drawing from skills honed through his journalism studies, not to mention a healthy affinity for William S. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, Reed penned a verse that depicted the experience of shooting up with stunning clarity and eerie detachment.

Amazingly, Reed had attempted to record the song during his days on the pop assembly line at Pickwick Records. “They’d lock me in a room and they’d say, ‘Write 10 surfing songs,'” Reed told WLIR in 1972. “And I wrote ‘Heroin,’ and I said, ‘Hey I got something for ya!’ They said, ‘Never gonna happen, never gonna happen.'” But the band had no such constraints while being bankrolled by Andy Warhol.

Working in the still-unfamiliar setting of a studio proved to be a challenge for the band at some points, particularly during the breakneck outro of “Heroin.” Maureen Tucker eventually became lost in the cacophony and simply put down her sticks. “No one ever even notices this, but right in the middle the drums stop,” she says in the 2006 documentary The Velvet Underground: Under Review. “No one ever thinks about the drummer, they’re all worried about the guitar sound and stuff, and nobody’s thinking about the drummer. Well, as soon as it got loud and fast I couldn’t hear anything. I couldn’t hear anybody. So I stopped, assuming, ‘Oh, they’ll stop too and say, ‘What’s the matter, Moe?’ And nobody stopped! So I came back in.”

8. Lou Reed dedicated “European Son” to his college mentor who loathed rock music.

One of Reed’s formative influences was Delmore Schwartz, a poet and author who served as his professor and friend while a student at Syracuse University. With a cynical and often bitter wit, he instilled in Reed an innate sense of belief in his own writing. “Delmore Schwartz was the unhappiest man I ever met in my life, and the smartest … until I met Andy Warhol,” Reed told writer Bruce Pollock in 1973. “Once, drunk in a Syracuse bar, he said, ‘If you sell out, Lou, I’m gonna get ya.’ I hadn’t thought about doing anything, let alone selling out.”

Rock & roll counted as selling out in Schwartz’s mind. He apparently loathed the music – particularly the lyrics – but Reed couldn’t pass up a chance to salute his mentor on his first major artistic statement. He chose to dedicate the song “European Son” to Schwartz, simply because it’s the track that least resembled anything in the rock canon. After just 10 lines of lyrics, it descends into a chaotic avant-garde soundscape.

Schwartz almost certainly never heard the piece. Crippled by alcoholism and mental illness, he spent his final days as a recluse in a low-rent midtown Manhattan hotel. He died there of a heart attack on July 11, 1966, three months after the Velvet Underground recorded “European Son.” Isolated even in death, it took two days for his body to be identified at the morgue.

9. The back cover resulted in a lawsuit that delayed the album’s release.

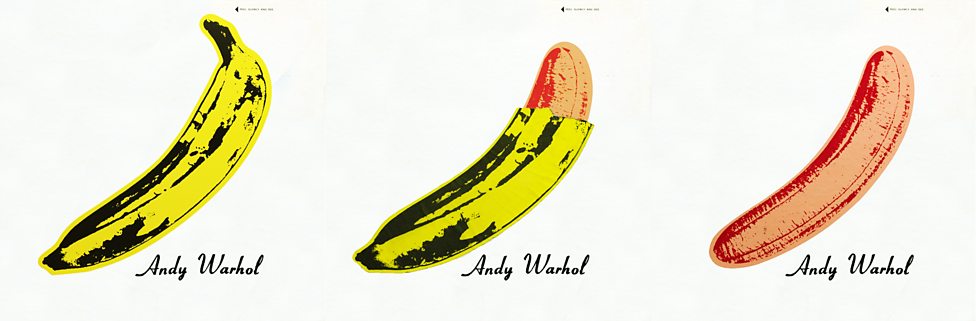

Being managed by Andy Warhol came with certain perks, and one was the guarantee of a killer album cover. While the artist’s involvement in the music was spotty, the visual art was to be his purview. Bored by mere static images, he devised a peel-away sticker of a pop art banana illustration, under which would be a peeled pink (and slightly phallic) banana. Aside from fine print above the sticker helpfully urging buyers to “peel slowly and see,” the only text on the stark white cover was Warhol’s own name, gracing the lower right corner in stately Coronet Bold – adding his official signature to the Velvet Underground project.

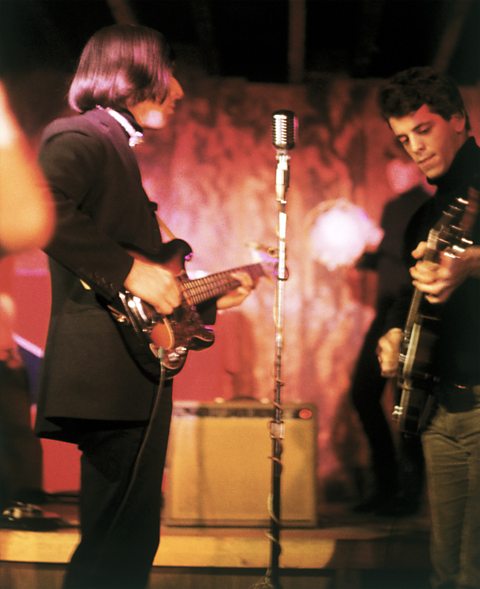

The promise of what was essentially an original Warhol print on the front of each album was a major selling point to Verve, the MGM subsidiary that had purchased the distribution rights to the tapes, and they shelled out big bucks to obtain a special machine capable of manufacturing the artist’s vision. Ironically, it was the comparatively traditional back cover, a photo of the band in the midst of an Exploding Plastic Inevitable performance at Norfolk, Virginia’s Chrysler Art Museum, that would cause the most headaches. A slide montage was projected onto the stage and the upside-down image of actor and Factory associate Eric Emerson from Warhol’s Chelsea Girls film could be seen. Emerson, who had recently been busted for drug possession and was badly in need of money, threatened to sue the label for the unauthorized use of his image.

Rather than pay Emerson his claim – reportedly $500,000 – MGM halted production that spring while they grappled with how to remove the offending image. Copies of the album were recalled in June, all but dooming its commercial prospects. “The whole Eric business was a tragic fiasco for us, and proves what idiots they were at MGM,” Morrison told Bockris. “They responded by pulling the album off the shelves immediately and kept it off for a couple of months while they fooled around with stickers over Eric’s picture, and then finally the airbrush. The album thus vanished form the charts almost immediately in June, just when it was about to enter the Top 100. It never returned to the charts.”

10. The release delay sparked Sterling Morrison’s intense, and often hilarious, hatred of Frank Zappa.

The tracks for the album were largely complete by May 1966, but a combination of production logistics – including the tricky stickers on the cover – and promotional concerns delayed the release for nearly a year. The exact circumstances remain hazy, but instead of holding the record execs responsible, or Warhol in his capacity as their manager, the Velvet Underground blamed an unlikely target: their MGM/Verve labelmate Frank Zappa.

The band believed that Zappa used his clout to hold back their release in favor of his own album with the Mothers of Invention, Freak Out. “The problem [was] Frank Zappa and his manager, Herb Cohen,” said Morrison. “They sabotaged us in a number of ways, because they wanted to be the first with a freak release. And we were totally naive. We didn’t have a manager who would go to the record company every day and just drag the whole thing through production.” Cale claimed that the band’s wealthy patron affected the label’s judgment. “Verve’s promotional department [took] the attitude, ‘Zero bucks for VU, because they’ve got Andy Warhol; let’s give all the bucks to Zappa,'” he wrote in his memoir.

Whatever the truth may be, Sterling Morrison held a serious grudge against Zappa for the rest of his life, making no effort to hide his contempt in interviews. “Zappa is incapable of writing lyrics. He is shielding his musical deficiencies by proselytizing all these sundry groups that he appeals to,” he told Fusion in 1970. “He just throws enough dribble into those songs. I don’t know, I don’t like their music. … I think that album Freak Out was such a shuck.” He was even more blunt a decade later when speaking to Sluggo! magazine. “Oh, I hate Frank Zappa. He’s really horrible, but he’s a good guitar player. … If you told Frank Zappa to eat shit in public, he’d do it if it sold records.”

Reed also had some choice words for Zappa over the years. In Nigel Trevena’s 1973 biography booklet of the band, he refers to Zappa as “probably the single most untalented person I’ve heard in my life. He’s two-bit, pretentious, academic, and he can’t play his way out of anything. He can’t play rock & roll, because he’s a loser. … He’s not happy with himself and I think he’s right.” The pair must have buried the hatchet in later years – after Zappa died of prostate cancer in 1993, Reed posthumously inducted him into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Count Basie,

Count Basie,  Kenny Burrell,

Kenny Burrell,  Kenny Burrell,

Kenny Burrell,  Artie Shaw and His Orchestra,

Artie Shaw and His Orchestra,  Frank Lovejoy, Night Beat, 1949

Frank Lovejoy, Night Beat, 1949 Jay Jay Johnson, Kai Winding, and Bennie Green,

Jay Jay Johnson, Kai Winding, and Bennie Green,  Moondog,

Moondog,  The Joe Newman Octet,

The Joe Newman Octet,  Cool Gabriels,

Cool Gabriels,  Johnny Griffin,

Johnny Griffin,  Various artists, Progressive Piano, 1952

Various artists, Progressive Piano, 1952